Transmoto’s 2014 250cc MX Bike Shootout

For 2014, the revamped quarter-litre motocrossers from Yamaha and Honda come up against refined offerings from Kawasaki, KTM, Suzuki and TM. But who stands tall in the cold, hard light of back-to-back testing? This article originally appeared in Transmoto Dirt Bike Magazine‘s 2014 February (#44) issue…

Young punks won’t remember this. But when Yamaha’s revolutionary YZ250F first arrived in 2001, we were all beside ourselves about the thing’s performance. The idea that a quarter-litre four-stroke could produce 30 horsepower and level-peg a 125cc two-stroke was incomprehensible at the time. It took a few years for the rest of the manufacturers to get their act together with a YZ250F rival, but by 2005, racing a 125cc two-stroke in the Lites class was a ticket to nowhere.

More than a decade on, and changes to the class eligibility rules – in Oz and New Zealand, anyway – sees these same four-strokes going head-to-head with 250cc two-strokes. So it’s a good thing that there’s been a second wave of four-stroke technology. The wholesale arrival of fuel injection in recent years has been accompanied by advances in inlet tracts, valve design and head efficiency, and most quarter-litre MX bikes now happily pump out between 36 and 40 horsepower (depending on whose dyno you use). In any case, combine 25% more power with improved throttle response, agile handling and weight savings, and you’ve got a recipe for fun – especially if you’re not a full-blown Pro who trains five days a week.

But who’s winning the arms race in the 250cc MX market these days? Can the overhauled 2014-model Yamaha and Honda – two of the class’ biggest-selling machines – unseat the Kawasaki and Suzuki, which have been considered class-leaders for a few years now? And what about the European contenders – Austria’s multiple title-winning KTM and Italy’s factory-inspired TM?

With the revamped up against the refined this year, the time was ripe for a showdown. So, to help paint a picture of what sort of rider, terrain and riding style each bike best suits, we descended on a private test facility at McLeary’s Ranch north of Sydney with six stock bikes.

Presented in alphabetical order, this is how each machine struck us…

TEST BIKE SET-UP

The bikes were tested in completely standard trim because this creates a level playing field and the most relevant feedback to readers – most of whom will buy a motocross bike off a dealer floor. All six bikes ran the same OEM set of intermediate-terrain tyres – either Bridgestone M403/404s or Dunlop MX51s. As the Suzuki and Kawasaki come with plug-in EFI mapping couplers in their parts kit, they both had the option of changing maps during the test. The other four bikes didn’t, as they require owners to purchase map-setting tools – an expense over and above the bike’s retail price. Similarly, we allowed mid-test adjustments to be made to the Kawasaki and Suzuki’s fork preload (as their Showa SFF forks have external spring preload adjustment). The Honda, KTM, Yamaha and TM couldn’t make on-the-fly fork preload adjustments for the simple reason that it’d require the fork legs to be split to do so. Shock spring preload was adjusted on all bikes to best suit each test rider’s weight and/or set-up preference.

SCORING & RANKING

The way bikes are scored in shootouts will always be a contentious one, and – surprise, surprise – you never get consensus from all manufacturers over the methodology. But, after staging dirt bike shootouts for 15 years, we’re confident that the way we go about it produces the most accurate and relevant results. In broad terms, here’s how it works:

• Testers fill out a detailed scorecard for each bike. That is then distilled into a score out of 10 for engine, suspension/steering and ergos/brakes. They do this alone to ensure their feedback is not influenced by other test riders.

•When test riders submit their scores, they are aggregated and subjected to a weighted average – 50% for engine, 40% for suspension/steering and 10% for ergos/brakes.

•We then sit down for a two-hour feedback session after the track testing to add dimension and detail to those scores. Here, the objective is to determine what sort of rider, terrain and riding style each bike best suits.

Why apply a weighted average to each bike’s scores? A few reasons:

•Because low scores for ergos (such as a too-soft seat or unconventional bar bend) are easy and relatively cheap to fix. Low scores for engine and suspension, on the other hand (poor throttle response at low revs or a deflecting fork, for example), are not only much costlier fixes; they also have a larger impact on the bike’s performance and lap time potential.

•If we didn’t apply a weighted average, it can create misleading results. Let’s say Bike A scores 9 for engine, 9 for suspension/steering and 6 for ergos/brakes. Bike B scores a 6 for engine, 9 for suspension/steering and 9 for ergos/brakes. Both bikes’ total score adds up to 24, or an average of 8 out of 10. In which case, their overall scores would be identical. But which bike would you rather buy? Naturally, Bike A – because with some added seat foam and a $100 handlebar with a better bend, you’ll be way ahead of the bloke who bought Bike B and then had to spend $1500 on a pipe, cam and head porting to bolster its engine performance from a 6 to a 9 out of 10. Weighting therefore minimises the risk that results are unfairly skewed. The shootout’s primary objective is to determine what sort of rider, terrain and riding style each of the six machines best suits.

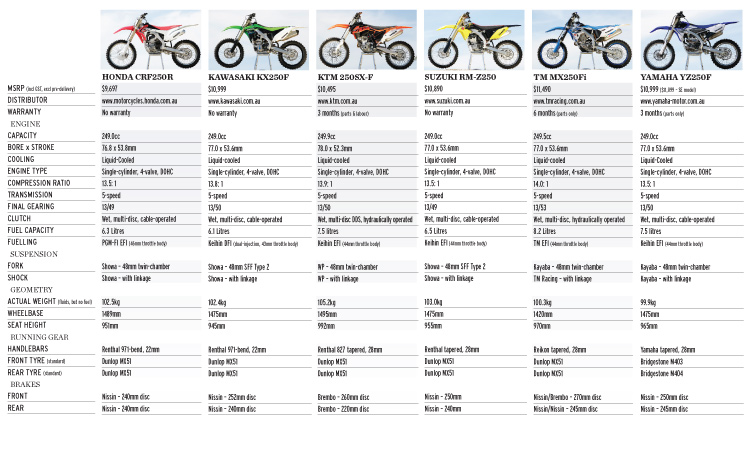

BIKE SPECS

ERGONOMICS

With its all-new bodywork, sixth-generation alloy frame and lowered centre of gravity (all of which was introduced on the CRF450R last year), the 2014 CRF250R looks and feels like a physically smaller and more compact machine than both its predecessor and the other five 250s. Even its wheelbase appears short, and its engine is so compact and upright (which allows the header pipe to run behind the frame’s downtube), it’s hard to believe this bike is actually packing 250cc.

Sitting on the 2014 CRF250R confirms those appearances. The seat is noticeably lower than the other five bikes, which makes the Renthal bars feel taller than average. You sit down into the bike, not up on it; almost like an enduro bike’s cockpit. The streamlined new plastics (which come with practical built-in lift points) combine with the smaller radiators to make the Honda’s cockpit super-slim and very easy to move about on. There’s nothing to snag your boots or kneebraces on, and smaller riders will be able to throw it around with lots of confidence. Taller guys, however, will feel cramped for legroom and as if they’re hanging off the bike’s arse-end when standing.

As it’s a departure from convention, the new Honda tends to polarise opinion. Some love its compact, slick, ‘scrub generation’ swagger; others reckon the return to the dual-muffler arrangement is a risky and regressive step. No matter what your take on its aesthetics, the Honda’s quality of finish is excellent across the board.

Thankfully, last year’s miniscule 5.7 litre fuel tank has grown to 6.3 litres, which’ll take the stress out of those long motos in the sand. On the downside, the CRF doesn’t come with skidplate or engine case protection. Plus each mufflers’ tiny outlets and the enclosed airbox confirms that Australia gets the Euro-spec bike (to ensure it meets the more stringent FIM noise emissions), which is much more restricted than the machine the American market gets.

And whatever happened to Hondas having the best brakes on the market? The stoppers on our CRF250R test bike were average. The Honda now runs the smallest front brake disc (240mm) of the bunch, but even with the lever adjusted fully out, it still came back too close to the bars before doing its job properly – leaving us to assume it would have benefitted from being properly bled.

POWER DELIVERY

Like its ergos, the Honda’s power also has a noticeably different feel to the other five machines. To begin with, its exhaust note is so quiet, it’s hard to believe you’re aboard a motocross bike. Which isn’t a problem, unless it comes at the expense of too much power. Sadly, it does. The 2014 CRF250R’s power is flat. It feels well down on throttle response and torque when compared to both last year’s CRF250R and to the other 2014-model 250s. You can feel the engine’s potential is there, but it seems pretty clear that the restrictive airbox and dual-muffler exhaust system have conspired to pacify the 2014 CRF250R – just as it did to last year’s CRF450R.

Even when you crack the throttle, the revs build very slowly, and at high revs, the Honda feels as if it’s trying to breathe through an environmentally conscious enduro muffler. You can hardly get a finger down the miniscule outlets in each muffler’s end-cap, which suggests Honda’s design team were thinking more about sanitising noise emissions than stimulating performance. And without the ability to breathe properly, the 2014 Honda just can’t compete on equal terms.

Admittedly, taking that sting out of the Honda’s bottom-end helps it hook up on skatey hardpack. But that’s where the benefits start and finish. In ruts, where you rely on instant power to help control the bike’s lean angle, the Honda left you dog-paddling. And in sandy terrain, you really feel this new engine’s lack of low-rev punch. You’re forced to set up earlier for turns, get on the gas before the apex and carry more corner speed because you simply can’t rely on the constipated power to blast your way out of there; not without a handful of clutch, anyway.

“The Honda is a light and agile and easy for small riders to throw around with confidence, but the new exhaust has made the power delivery decidedly flat.”

Interestingly, even when you take the seat off, the Honda’s exhaust note cracks noticeably harder. So there’s definitely huge gains to be had with an aftermarket exhaust and/or airbox mods. And we’re guessing that Moto Tassinari’s Air4orce intake systems will do a big trade with Honda owners this year.

All that said, our lap times proved that the Honda wasn’t as sluggish as it felt. Even though most testers said they felt well off the pace on the super-quiet Honda, the stopwatch proved otherwise. Yes, this bike is deceptively fast, but you still have to work it a lot harder to produce the same lap times. Perhaps this explains why the all-new 2014 Honda is $1000 to $1500 cheaper than its rivals; so anyone who intends to race one will have some spare change to throw at aftermarket mods that’ll unleash the bike’s true potential.

HANDLING

It doesn’t take long to realise that this new chassis and bodywork combine to make the Honda one of the most agile and flickable motocross bikes you’ll ever ride. It’s incredibly easy to flick from side to side or pull back into line if it gets away from you in the air, and the low seat height lets you square off corners at an instant’s notice. It is, without doubt, the best rut machine of the bunch. Even if you’re late on the anchors, the CRF always manages to pick up that inside rut you never thought you could make. And once in the thing, the bike holds its line so well, it gives you the confidence to ramp up your corner speed.

The Honda’s chassis isn’t as confidence inspiring at high speeds, though. The rougher and more rutted our test track became, the less inclined test riders were to push the Honda. The bike’s short wheelbase feel may pay dividends around tight turns, but its chassis doesn’t give you the confidence to hang the rear-end out recklessly through fast sweepers.

But that’s not all geometry-related. Of all six bikes, the Honda’s Showa suspension clearly has the softest set-up, and it’s the first machine that’ll require firmer springs and/or valving. For a quick rider over 75kg, the Honda’s poise is easily unsettled around faster turns because the front-end tends to sit too far down in its stroke, and the chassis has a nervous feel through a decent series of downhill braking bumps – despite the steadying influence of the bike’s steering damper.

We managed to improve the chassis’ balance and stability by firming up the fork and running some extra sag in the rear-end (from 102 to 106mm), without compromising its rut-railing performance too much. Which indicates the Honda is particularly sensitive to shock preload settings. But if you’re using most of your clicker adjustment to improve the bike’s ride over braking bumps, it suggests the base settings are well off the mark for all but the lightest pilots.

ENGINE MODS

In search of more bottom and mid-range punch, there’s a new high-compression piston, ramped-up compression ratio (13.5: 1) and a completely revised cylinder head design. And to complement the engine mods, a new dual-timing PGM-FI fuel injection system is fitted for better response at partial settings and more over-rev. Also, the transmission’s gears are now beefier for added durability.

NEW-GEN FRAME

To lower the bike’s centre-of-gravity and improve agility, it gets the more compact sixth-generation rolling chassis whose twin-beam spars now meet the head tube much lower. The radiators are also mounted lower. Interestingly, Honda has revalved its twin-cartridge 48mm Showa fork rather than fitting the Kayaba PSF (Pneumatic Spring Fork), which wasn’t well received on last year’s CRF450R.

DUAL MUFFLER

A ‘twin rhombohedral’ dual-muffler exhaust system is fitted to centralise mass and sharpen handling. It produces a whisper-quiet exhaust note, but feels to be very restricted. To complement the new frame, the bodywork is slimmer and more streamlined. It comes with reinforced attachment points, built-in lift-points on the rear fender and a larger 6.3 litre fuel tank (up from 5.7L).

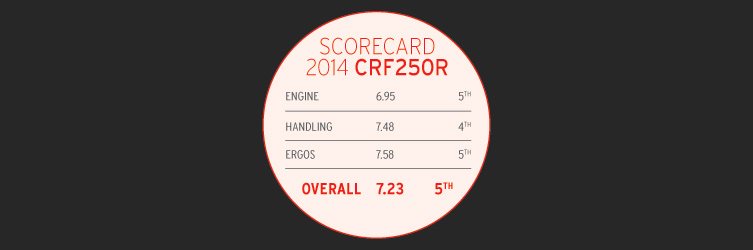

SCORECARD

ERGONOMICS

Kawasaki’s engineers have worked hard in recent years to fine-tune the ergos and cockpit comfort on both their 250 and 450cc motocross bikes, and the result is a workspace that few now take exception to. The seat is comfortable without being cushy and all controls fall perfectly to hand. It’s not quite as slim through the girth as the Suzuki and Honda, and in the natural attack position, you do tend to sit a little further back on the Kawi’s saddle. Compared with the other Japanese bikes, the KX250F’s taller bars give the bike a slightly bigger and more spacious feel. That’ll appeal to taller riders and guys who like to stand a lot in the saddle, but shorter guys tend to feel that the combination of the tall front-end and soft seat foam make you feel like you’re sitting down into the Kawi’s cockpit. Combined with the wider-than-average Renthal handlebars, that can take a little getting used to.

What we’d like to know is why the KX250F doesn’t comes with the same adjustable pegs that its 450cc big brother does. That added adjustment was well received on the KX450F, and it makes even more sense for the 250, where faster-growing young jockeys tend to cut their teeth. Similarly, the 250 also has fewer handlebar adjustment options than its big brother. And, at 6.1 litres, it now has

the smallest fuel tank in the class.

That said, the KX250F does comes with the plug-in DFI couplers to adjust engine mapping and the bar-mounted Launch Control Mode button for 2014. The external adjustability of its Showa SFF fork is also a bonus; as is the fact

it gets a hard-plastic skidplate and case guard ‘wings’ as standard equipment. The 2014 KX250F now joins the rest

of the KX and KX-F family with the white rear guard and black rims. They combine to make it a cool-looking, Ryan Villopoto-inspired rig, but they’re both more susceptible to wear.

POWER DELIVERY

The KX250F has always had one of the strongest all-round engines in the class, especially since the Keihin dual-injection EFI system was introduced last year. Aside from the addition of the bar-mounted Launch Control and some tweaks to the transmission, the Kawi’s engine hasn’t changed for 2014. But that doesn’t mean it’s not still right there with the best of them.

The KX250F might not have the Suzuki’s class-leading torque. It doesn’t have the Yamaha’s instantaneous throttle response. And it can’t pull quite as hard as the KTM and TM at high revs. But it’s never far off the mark in all three

areas. In fact, there is absolutely no weak point of the Kawasaki engine, and that’s what makes it so versatile and easy to adapt to for riders of varied abilities and weights. No matter where you are in the rev range, the power is there and ready to rock.

“With broad and responsive power and a balanced, predictable suspension package, the 2014 KX250F remains an incredibly forgiving and versatile ride.”

The Kawi’s power delivery is most like the Suzuki’s. It’d got a broad, strong, smooth surge of power that lets you get the rear wheel hooking up effortlessly on hardpack, and yet there’s enough punch and throttle response to power out of fluffy berms without having to resort to the clutch.

And if you need to hold gears longer to avoid too many shifts, the Kawi’s ample over-rev will happily accommodate that, too.

So, whether you’re confronted by slow point-and-shoot terrain, fast sweepers, slick hardpack, tacky clay or sandy whoops, the Kawi’s versatile engine has an answer for every occasion. It mightn’t be a standout in any one area, but as an overall package, it’s an incredibly user-friendly little mill that you quickly adapt to. Plus it has the option of changing maps via its plug-in EFI couplers. Cool option, but why not make it more convenient for on-the-fly adjustment via a bar-mounted switch?

HANDLING

Like its predecessors and 450cc big brother, the 2014 KX250F’s chassis is well balanced front-to-rear. With its slightly wider ergos and taller bars, the Kawi doesn’t tip into and rail ruts as well as the Honda, nor does it change direction as effortlessly as the Suzuki. But its steering manners remain pinpoint and confidence-inspiring across a variety of terrain. Again, the Kawi’s handling doesn’t prompt you to sing its praises in any one particular area, but it does absolutely nothing that allows you to fault it, either. There are no nasty surprises with the Kawasaki’s chassis or suspension. You can just get on the thing and ride it, and it’ll behave predictably, whether you’re ripping into skatey hardpack

or deep loam.

In terms of firmness, the KX250F’s suspension at both ends is mid-pack, but the chassis’ most endearing quality is how forgiving it is. Of all the 250s, the Kawi was least in need of radical clicker adjustments to keep test riders of varying weights happy – meaning it’s got the broadest window within which the chassis set-up feels good. It’s a versatile suspension package; it’s plush for even the lightest test riders, and yet progressive enough to resist bottoming in the hands of a heavyweight tester. The predictability of the rear-end is particularly good under acceleration, where the rear-end works in unison with the broad and smooth power. Whether you throw sharp-edged bumps or rolling sand whoops at it, the KX-F’s rear-end retains a very planted feel and tracks dead straight.

The Kawi’s SFF fork, however, isn’t as impressive as the Suzuki’s when push comes to shove in the hands of a faster rider. Even though the two SFF forks appear identical, the Kawi’s internals aren’t quite as sophisticated as the Suzuki’s, which is why Pro Circuit now sells a Kawi-specific LSV (Low-Speed Valve) kit. The idea of PC’s performance kit is that it helps the KX-F fork sit up in the plusher part of its stroke more of the time. So, while the Kawi’s rear-end is a little livelier than the Suzi’s through a set of braking bumps, it has more to do with the fork’s action than the shock’s.

BODYWORK

The KX250F joins the rest of the KX

and KX-F family with white sideplates and rear guard this year. There are also new soft-compound grips, and updated radiator shroud decals, and the Kawi remains the only bike with black rims. The Showa Type 2 Separate Function Fork (SFF) gets revised settings to improve the initial through mid-stroke damping, and the Showa shock absorber also gets minor damping tweaks.

LAUNCH CONTROL

To assist rear wheel traction out of the start gates, the 2014 KX250F gets the bar-mounted Launch Control Mode button, which was first introduced to the KX450F in 2012. As soon as you click third gear, it disengages. The transmission’s gear selector dogs have also been modified for slicker shifting and a more positive feel at the pedal.

ENGINE MOUNTS

The front engine mounts are made thinner and more flexible for 2014. This is to optimise frame rigidity and improve front-end feel and traction. It may sound like a stretch, but most major manufacturers have made similar mods in recent years (to frame mounts and/or skidplate fixture points) to ensure they don’t prevent the frame from flexing how and where it’s designed to.

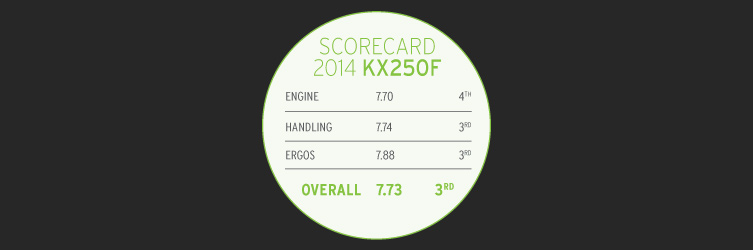

SCORECARD

ERGONOMICS

When KTM made the radical changes to its 2013-model SX-Fs, the Austrian machine’s ergos took on a more conventional – almost Japanese – feel for the first time. Sure, the KTM remains the only bike that doesn’t run an alloy frame, Kayaba or Showa suspension and Nissin brakes, but the 250SX-F is certainly nowhere near as ‘foreign’ as it was a few years back – aside from that funky-looking front guard, that is! The 2014 Kato is a fraction wider through the girth than the super-slimline Honda and Suzuki, but not badly so. Its bars are a little taller than average, but the seat/bars/footpeg triangulation is difficult to distinguish from the Japanese bikes.

The cockpit’s controls all have a light, smooth and precise feel and the Kato is still the only bike of the bunch to come with an electric-start. Having worked with footwear giant, Adidas, the seat foam is a little firmer for 2014. It’s still comfortable, but gone is the risk of bruising your arse cheeks from hitting the frame rails. Unfortunately, the thing is still too slippery. It simply doesn’t have the same level of grip as the other five seats.

Interestingly, the KTM is now the heaviest bikes in its class at 105.2kg. Sure, you’d expect the electric-start componentry to add a kilo or two to the bike (which is something most of us would be willing to put up with for the convenience it offers), but the Austrian machine is now more than 5kg heavier than the Yamaha. KTM’s engineers seem to have lost their obsession with weight, as they often point to the fact their world title-winning factory bikes are the heaviest in the paddock. These days, they’re much more concerned with reducing reciprocating mass because of its impact on the bike’s handling.

KTM’s Brembo front brake remains stronger than the Nissins for a given input at the lever, and yet the mods to the master cylinder and pads for 2014 have improved its feel and modulation. But the squeaky rear Brembo brakes on the Kato were touchier than the other machines’ rears.

POWER DELIVERY

KTM has seldom short-changed customers when it comes to power, especially with small-capacity machines. And its 250SX-F has delivered class-leading dyno numbers for as long as we can remember. Given that the 2014 engine only really gets a minor mod to the starter freewheel assembly, there are no surprises with the Kato’s power delivery this year. It remains one of the strongest engines through the mid-range and at high revs – which you’d expect from a bike with the largest-diameter piston (78mm) of the six – but it does take longer than the Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki to get into the meat of its power and start to boogie. To get the most out of the Kato, you do need to rev it hard. Which is exactly as KTM’s designers intended it. When they went in search of more bottom with the 2012 250SX-F, the market complained about the corresponding loss of top-end, prompting KTM’s move to the over-square, high-revving platform the 250SX-F has now used since 2013.

We’re not saying the 250SX-F has poor bottom-end. Far from it. We’re simply pointing out that the Austrian bike can’t match the standout throttle response and low-rev torque of those three Japanese machines. And anything the Kato gives away at lower revs, it more than makes up for up top. The KTM keeps pulling hard all the way to its 14,000rpm rev limiter.

The KTM’s power works best around sweeping turns where you can put its prodigious mid and top to good use, but punching out of slower ruts or power-sapping sections of track requires you to be on your game with gear selection and/or clutch use to keep the bike

on the boil.

“The KTM has the strongest brakes and firmest suspension set-up, and feels most at home at higher revs around fast, flowing tracks.”

Even though the KTM has dropped its sixth gear for 2014 (and retained the same gear ratios for first through fifth), the 13/50 final gearing leaves it noticeably taller than the other fives bikes. And many Clubman and Pro riders have found the KTM works better with the 51-tooth rear sprocket. It brings the engine up in the rev range on corner exits, and helps the bike punch off turns better. It also makes the bike easier to ride in power-sapping loam, where it takes a while to recover after getting bogged down.

HANDLING

The 250SX-F clearly has the firmest and more race-oriented suspension of all six bikes, and seems to be set up for an 85kg rider, rather than the 75kg bloke that 250s are typically sprung for. We’re not talking supercross-spec suspension here, as it doesn’t deflect off small, square-edged bumps. But the WP fork and shock definitely transfers more of the track’s bumps back though the rider’s arms and legs. This suspension doesn’t like to be ridden at Clubman pace; the KTM has a race-oriented set-up that prefers to be thrown into obstacles hard. Riders under 75kg will be looking to soften the suspension

via springs or valving, or both.

Like the Honda, the KTM tends to have an arse-high feel with standard trim – largely because the fork tends to ride too far down into its stroke much of the time. And this can give the fork a harsh feel through a series of decent-sized braking bumps (strangely, this is at odds with the 450SX-F’s WP fork, which sits up in its stroke better than the Showa and Kayaba forks). But with more compression clickers to help hold the front-end up, the fork’s action actually becomes more progressive. If you combine that with a little more sag in the shock (we found 106mm race sag works much better than the standard 100mm), the KTM is quickly transformed into a much better balanced and more stable bike over downhill braking bumps.

Like the TM, the KTM feels like it carries its weight higher than the Japanese bikes and requires more effort to wrestle it from side to side. Plus our smaller testers found that the tall bars makes it more difficult to get over the front-end of the machine, and that the bike responded better to steering with the rear wheel through flat turns. It’s true that a set of lower-bend bars will sort this issue. But with the standard hangers, you do have to be a little more premeditated in the way you approach corners, rather than just throwing the bike where you want it at the last moment.

That said, the taller handlebars put you in a very strong standing position on the bike. If you ride like stand-up king, Stefan Everts, you’ll love it. If you’re more of a sit-down-and-hold-it-on Justin Barcia kind of guy, a lower set of bars will make a big difference by putting you in a much more commanding position in the KTM’s cockpit.

TRANSMISSION

To save 250g, sixth gear is removed for 2014 (though there’s no change to the remaining gear ratios or 13/50 final gearing combo), leaving the 250SX-F with a five-speed transmission – like all its rivals. The freewheel mechanism on the starter motor has been made more durable, while the water-pump cover is redesigned and runs an updated gasket.

SEAT

Working in conjunction with footwear giant, Adidas, KTM’s designers have made the seat firmer for 2014 without making it uncomfortable for longer rides. In fact, the firmer seat foam (with noticeably more padding at the rear) actually prolongs the onset of monkey-butt and aids easy movement around the cockpit. A more compact, re-routed wiring harness is fitted.

MASTER CYLINDERS

The Brembo brake and clutch master cylinders get a matching black finish and, as a majority of riders now run their front brake lever relatively flat, the reservoir has been designed to sit more level (meaning you no longer have to tilt the perch forward to fill the reservoir). To improve progression, the piston diameter has been reduced from 10 to 9mm, plus there’s a new brake pad material.

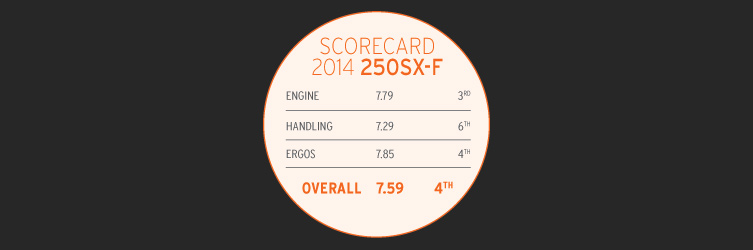

SCORECARD

ERGONOMICS

Suzuki hasn’t made a significant change to the ergos of their RM-Zs since 2008, which just goes to show how right they got this machine’s cockpit to begin with. The 2014 RM-Z250 might have one of the hardest seats, but all six test riders said they adapted to its ergos quicker than any other bike; so much so that they all reported being comfortable enough to get aggressive on the Suzuki after just a few corners.

The RM-Z250’s seat isn’t as flat as the TM, Yami and KTM’s, and it does ramp up a little more at the junction with the alloy tank. But that occurs so close to the steering head that it doesn’t come in to play. Of all the bikes, the Suzuki has the slimmest girth and the firmest and narrowest seat, which gives it a race-spec feel out of the crate. Like the TM and KTM, you sit tall on the RM-Z250 – on it, rather than in it. Its controls fall perfectly to hand and there’s nothing on the frame or bodywork to catch your boots or impede your movement. Combine this with its lowish and slightly swept-back bars, and the Suzi’s seat/pegs/handlebar set-up puts you in a very commanding position in the cockpit. In the neutral seated position, your head is so far forward that you’re actually looking down at the front plate. In other words, the Suzuki’s neutral position and attack position are one and the same, and this alone insists you ride the bike with attitude and aggression.

New-generation riders – who all seem to love the extra flat-turn control that low handlebars create – will quickly warm to the Suzuki’s cockpit. With the standard Renthals, however, riders over 182cm will find themselves stooping over a

fair bit while standing on the bike, so they’ll probably want to fit a higher-bend bar. The Suzuki’s Nissin braking package also deserves a mention – the rear in particular. With such good feel, it definitely helps you get the bike’s rear-end to squat and settle through braking bumps, and you rarely get an unintended lock-up on the way into tricky ruts on the RM-Z250.

POWER DELIVERY

What a powerplant! The RM-Z250 has always been one of the strongest 250s at lower revs and, despite Suzuki claiming that the revised ECU settings are designed primarily to improve the bike’s starting ‘performance’, the 2014 bike sure feels like it’s found even more grunt through the bottom and mid (since our shootout, that’s been confirmed by a few independent dyno testing, plus the owners manual confirms the 2014 fuel pump has a different part number). The Suzuki’s power is not quite as responsive as the free-revving Yamaha, but nothing can match its torque. And that gives the RM-Z the broadest, most tractable and user-friendly power of all six bikes. It’s got the sort of crisp, roll-on-style power that you just don’t expect a 250 to be capable of. If you find yourself in too tall a gear for a corner exit or hill, the Suzuki isn’t bothered. It just grunts its way out of the situation, no questions asked.

“The RM-Z250’s magic comes from how well its fast-turning chassis, aggressive ergos and torquey power delivery all work in perfect harmony.”

This 250’s power is so versatile and forgiving, you can virtually ride it like a 450, which means you can get away with significantly fewer gear changes. On several sections of our test track where the other five bikes would all require second, third and fourth gears, the Suzi will happily process the section using only third and fourth. And as we all know, reducing shifts and clutch use quickly translates into a greater ability to focus on line selection, rather than keeping the power in its sweet spot. Even in slippery conditions, the Suzi gets so much drive that few testers even bothered to try the alternative map (accessed via a plug-in coupler, like the Kawasaki). The bike’s instant, predictable power makes life much easier around ruts, too, where it works in perfect harmony with the agile chassis and pinpoint steering.

For guys who don’t like to bounce off the rev limiter all day – which isn’t the best way to ride a 250F – the Suzuki will endear itself very, very quickly. It doesn’t quite have the top-end of the TM, KTM, Kawi or Yami, but that doesn’t matter around most tracks because the Suzuki gets there a whole lot quicker. And, unlike most 250s, it really doesn’t care if you don’t time your gear-shifts perfectly.

The only negative comment about the RM-Z’s engine throughout the entire shootout was the reference to the strange buzzing noise the exhaust makes when you button off. But that’s it. No wonder all six test riders ended up scoring the Suzuki as the best – or equal-best – engine.

HANDLING

If you thought the Suzuki’s engine was impressive, wait until you get the drum on its handling. Again, five of our six test pilots rated the Suzuki as the best-handling bike – and not only because it turns significantly better than all its rivals. Its tweaked suspension settings – the SFF fork in particular – gives the bike an unflappable, confidence-inspiring ride. Under acceleration, the rear-end squats and drives beautifully, allowing the rear wheel to hook up in situations where other bikes can’t. And through braking bumps, the Suzuki retains its composure when the other machines start dancing around. It hugs the ground so well over a series of braking bumps, you can see it from the sidelines.

The RM-Z’s real magic, though, comes from how well its chassis, ergos and torquey power all complement each other. With a seating position that puts you right over the front of the bike and a chassis that likes the rider loading

up the fork, the RM-Z’s front-end gives you plenty of feedback before it lets go. It gives you so much confidence to put the bike wherever you want, whenever you want. It’s easy to get in and out of tight corners and rutted turns, it’ll hold its line around off-cambers, and it’ll square off a corner with bugger-all rider input. There’s no need to wait for a bump or berm to turn off; you can just plant the front wheel and it’ll respond. Whether conditions are tacky or slick, the Suzuki makes you feel like you’re always riding on a fresh set of hoops and a freshly prepped track.

Its suspension action isn’t as plush as the Honda’s over the small bumps. And it might not be quite as unflappably stable as the Yamaha over high-speed bumps. But the Suzuki is better than the other five bikes pretty much everywhere else.

FORK SETTINGS

Even though there’s no mention of it in Suzuki’s upgrade PR, the settings in the Showa SFF fork feel better in 2014. Note also that, compared with the RM-Z450, the 250’s fork stanchions are machined differently and its triple clamps are 5mm wider apart to allow optimal fork flex. That’s why Matt Moss’ title-winning RM-Z450 race bike runs the 250’s triple clamps.

ENGINE MODS

The ECU (or ECM – Electronic Control Module – as Suzuki likes to refer to it as) has been updated to improve the bike’s starting and to generate more bottom-end and mid-range grunt. Aside from that, the RM-Z’s four-valve, DOHC powerplant is said to remain unchanged from last year. Funny that, because it actually feels decidedly more torquey, and recent dyno runs confirm that.

BODYWORK & GRAPHICS

Suzuki has never been big on throwing elaborate-looking graphics on their RM-Z range. And not everyone was a fan of the black rear guard that they first fitted to the 250 last year (it prompted analogies with cobbled-together FMX bikes). For 2014, the RM-Z250 gets updated bodywork with new two-tone radiator shrouds, yellow sideplate number backgrounds and ‘fresh’ graphics.

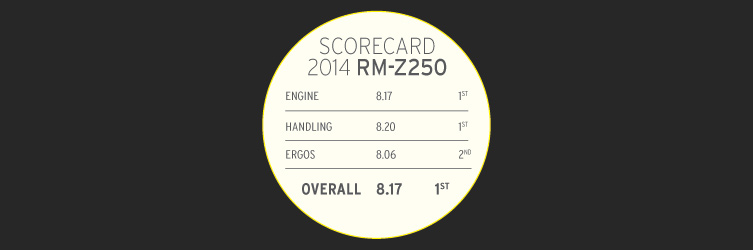

SCORECARD

ERGONOMICS

To look at, the TM is the most unconventional of the group, but not in a bad way. Unlike the other five bikes – which are, let’s face it, pretty conservative-looking offerings – this Italian machine wouldn’t look out of place alongside factory bikes on the startline of a Motocross GP. Out of the crate, its comes with a hard-plastic skidplate (with built-in engine case protection), a HGS exhaust system (with Powerbomb-style header pipe), billet hubs and triple clamps, blue anodised Excel rims, oversize 270mm front brake disc, and an excellent quality of finish – something that Italian manufacturers haven’t always been renowned for.

As different as the TM appears, its bar/seat/peg relationship is pretty similar to the other five machines. And despite its larger fuel tank (claimed to be 8.2 litres, but which was able to swallow 9 litres of juice at the shootout), it’s just as slim through the girth as the other five bikes. But its Reikon handlebars do have an unusual feel. They’re tall and swept back and slightly narrower than the other bikes’. Unlike the other five machines (which all come with rubber-mounted bars), the TM’s handlebars are hard-mounted to the top triple clamp. Racers will love this, as the things won’t twist like rubber-mounted bars tend to in even the smallest crash, but it also means there’s no adjustment for different sized riders.

The TM’s seat is the flattest and hardest of the group – by a long shot – and that reinforces the race-oriented feel of its cockpit. It’s the easiest bike to get forward on – so much so that you need to be careful not to slam your goolies straight into the fuel cap when you drop into the seat for a corner entry.

The front brake runs an unusual combo of Nissin master cylinder and Brembo calliper – theoretically, to offer the best of both brands. It has a bit of a ‘wooden’ feel in that it was either on or off (and yet still didn’t have the stopping power of the other bikes), though the Nissin/Nissin rear brake works really well.

POWER DELIVERY

The TM uses the identical 77 x 53.6mm bore and stroke as the Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha, but the Italian-made TM delivers a much different style of power. In short, the TM likes, wants and needs to be revved. Of all the bikes – even the highly restricted Honda – the TM’s got the mellowest bottom-end. That’s good for off-camber hardpack situations, but if you need to steer the bike with the rear-end or fire out of a soft berm, the TM is rarely at-the-ready. It needs a handful of clutch and throttle to transport it into its party zone.

The TM builds its power more gradually than the other machines, and with a smooth transition from bottom to mid-range, it manages to get its power to the ground effectively when traction is at a premium. But it doesn’t produce the sort of torque needed to pull third gear around too many corners, and it’s not until you get past 9000rpm that this little rocketship really comes alive. Up in its rev range stratosphere, the MX250Fi is much more convincing, and it actually takes quite a few laps to get a feel for just how hard you can rev this machine. It’s only when you force yourself to hold gears for another 1000 to 1500rpm that you start to get a feel for what this powerplant is capable of. It just keeps making power way beyond when you’d expect it to sign off, and still rarely bothers the rev limiter. Not surprisingly then, the TM is much more comfortable on fast, flowing tracks, and needs a lot of deft clutch use to get around point-and-shoot type tracks effectively. It’s more suited to an aggressive rider as you really can’t afford to be lazy aboard it. If the Suzuki is the easiest engine to adapt to, the TM is the most difficult in that you have to very consciously ride it like a two-stroke to keep it in the zone and on-song.

“It may look and feel different to the other five bikes, but the TM has got the power and poise to run with the class’ frontrunners in the hands of an aggressive rider.”

The bike’s 13/53 final gearing combo sounds short, but its ratios are spread nicely and well matched to the transmission’s internal ratios and free-revving power, and the Brembo hydraulic clutch has a light pull and good feel. Though, with the narrow band of power, we did find ourselves caught between second and third gears on several corners. It is interesting that TM has much more engine braking effect than all the other bikes. Perhaps that’s a legacy of the fuel-injection system, which, like the shock absorber, is designed and built in-house.

And even though the difference between the two maps is minimal, having the bar-mounted OTF dual-map switch (which is reprogrammable) is a nice option.

HANDLING

At just over 100kg (fluids, but no fuel), the TM is a poofteenth away from being the lightest bike on the digital scales, but it doesn’t feel like that on the track. That may have something to do with the fact its tall handlebars make it harder to flick from side to side through chicane-style turns. But there’s more to it than that. Like the KTM, the TM carries its weight higher than the Japanese machines, meaning it needs a more conscious effort from the rider to change direction.

The TM’s chassis and suspension is well balanced, and its shock absorber works very well (as it does on TM’s range of enduro bikes). Both fork and shock have a plush ride over the small, choppy bumps (even though the rock-hard seat can make you think otherwise to begin with) and with plenty of progression and bottoming resistance, the bike remains really stable through braking bumps.

And while the tall, flat, rock-hard seat allows oodles of mobility in the cockpit, we found that can actually be a bad thing. Why? Because it’s not easy to plant your arse exactly where you plan to for cornering. Early in the day, when ruts or berms weren’t yet formed, the TM’s front-end tended to tuck under because testers were getting too far forward in the saddle to get the front tyre to bite. Later on, when we were turning off ruts or fluffy berm cushions, the bike tended to push the front-end because testers were sitting too far back in the saddle. It all came down to where you ended up sitting on the plank-flat seat.

Make no mistake, though; the TM is a damn good thing and our lap times proved the Italian bike is very competitive. But its chassis seems to have a narrower set-up window inside which it works well, and you do need to be more conscious about both the position of your bodyweight and where you are in the rev range to keep the TM in its sweet spot. The bike’s technician (who is also TM’s Australian importer) was adamant that 40mm static sag is a critical measurement for the MX250Fi, and he was reluctant to tweak the bike’s shock preload too much as a result.

FORK SETTINGS

The TMs brought into Australia all get a Kayaba fork (the European market gets a Marzocchi) and TM’s own shock absorber. TM’s 48mm AOS-style Kayaba fork is similar to what the Yamaha runs, though it uses 15mm longer fork springs and slightly different internals. Spring rates for fork and shock remain unchanged (0.46 and 5.4kg/mm, respectively), and both ends get revised valving for more progression this year.

ENGINE

For 2014, the piston gets a new crown design to improve power and torque. It’s designed specifically to work in conjunction with the new cylinder head (whose volume diverges from the enduro models this year), the new inlet cam and the larger throttle body diameter (44m) used in TM’s own fuel-injection system (which also gets revisions to ignition timing and fuel maps for 2014).

TRIPLE CLAMP

The TM’s tapered Reikon handlebars are hard-mounted and the triple clamps are billet alloy. For 2014, the clamps’ offset is reduced to 23mm (from 25mm) for more stability during turn-in and at high speed. While the bike’s specs say the fuel tank is 8.2 litres, it’s actually closer to 9 litres, but the extra capacity doesn’t make the ergos any wider.

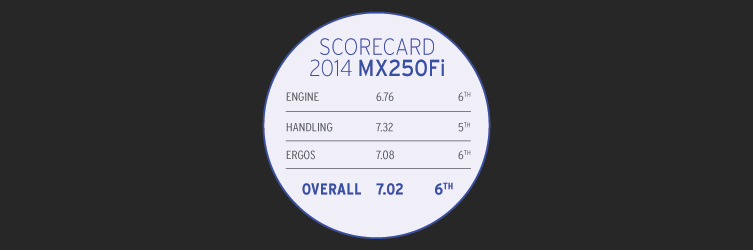

SCORECARD

ERGONOMICS

With the airbox and air filter relocated to above the all-new reverse-mounted fuel-injected engine, there was always going to be significant change to the 2014 YZ250F’s cockpit – which is now identical to the YZ450F’s. The new tank is a bit taller and broader in the ‘shoulders’ than last year’s bike, and the radiator shrouds are wider than both its predecessors and the other 2014 250s. But that ‘taller shoulders’ impression is largely an optical illusion created by the relative position of the tank and front guard. Don’t believe us? Draw a straight line from the seat and tank through to the front guard on all the bikes. See? You can on the other machines, but not on the Yami.

While the Yamaha may be wider in some areas, the dimensions that matter – the contact points with your legs and knees – remain very similar, and it’s actually difficult to detect the added girth when you’re standing or sitting on the bike. Okay, it’s not the slimmest 250cc MXer on the market and you do notice the 450-esque ergos is when you get right up the front of the bike. But it’s nothing like the 2013 YZ450F, whose super-splayed shrouds actually forced you back

on the saddle through tight ruts.

If anything, the new YZ250F’s seat is a little taller and flatter than last year’s, and with no fuel cap to punctuate proceedings, its super-smooth junction with the ‘tank’ allows you to get way forward in the saddle. The cockpit is more compact this year and, as you tend to naturally sit further forward on the bike, gone is that extra legroom under the bars that taller riders liked about the 2013 YZ250F.

The bike’s grips are hard and, as with all the Japanese bikes, the rubber-mounted bars will be met with mixed reactions. And, like the Honda, there’s no skidplate or case guards to protect the engine cases. But, those small gripes aside, there’s little to complain about. Yamaha has done a very good job of minimising the impact that the wholesale changes to the bike’s engine, inlet tract, fuel tank and bodywork have had on the ergos. It’s still the homely, comfortable cockpit that the market has come to expect from the YZ250F.

POWER DELIVERY

How convenient that the Yamaha is last in the alphabetic order, because in many ways, this shootout is largely about how this all-new machine – the pioneer, and the biggest-selling bike in the class for 13 years – slots into the mix. As our standalone test in the last issue proved, this new four-valve, fuel-injected donk leaves it predecessor for dead. The 2014 bike comes with a quantum leap in power, and one that actually changes the way you ride the machine. For starters, it fires into life much better than the carb-fed 2013 bike and idles in a smoother, more refined way. With a big outlet in the muffler’s end-cap, the exhaust note is throatier, and just sitting there in neutral, you can notice how much quicker its revs build when you blip the throttle. You also notice the very audible induction noise. And once you ride the thing, those differences are exaggerated.

As soon as test riders finished their initial stint on the Yami, the first thing they all referred to was the instantaneous nature of the engine’s throttle response. No matter where you are in the revs, this new 250F just jumps to attention and lurches forward. It’s like a 450 in the sense that if you want power, it’s there; ready and willing, without hesitation. Like the Suzuki and Kawasaki, the Yamaha can get away without any assistance from the clutch for a large portion of its broad rev range. It doesn’t fall off the power if you get caught in the wrong gear in sandy conditions, and it makes it easier to clear a jump with minimal run-up from an inside line.

But this new, fuel-injected engine’s improvements aren’t confined to low-rev response. With the power coming on earlier, there’s a smoother transition into a meatier, torquier mid-range. And up top, this EFI engine pulls hard all the way to the 13,500rpm rev limiter. It puts the 2013 YZ250F – whose engine has long been renowned for its top-end – to shame, and almost matches the two top-end screamers of the 2014 bunch: the KTM and TM. That extra breadth of power means you no longer have ride the Yamaha like a rev maniac to get it to work.

“The ALL-NEW YZ250F has the snappiest and most responsive power of the bunch, and a chassis that combines low-speed agility with high-speed stability.”

The YZ-F’s free-revving power creates the impression it’s got a lighter flywheel than the other five machines. It’s punchier than the Suzuki and pulls a little harder at high revs, too, but the Yami is not as smooth and torquey as the RM-Z. So on slick hardpack tracks, the Yamaha can get you into trouble if you’re not precise with throttle inputs. When there’s a lot of grip, however, the Yamaha’s super-responsive, snappy engine comes into its own. Stomp the throttle and it launches on command, boosting from one section of the track to another as if it’s got 350cc under the hood.

HANDLING

Yamaha says the 2014 YZ250F is 1-2kg heavier than its predecessor – due mainly to the addition of the EFI componentry – but it still tipped our scales as the lightest machine (99.9kg). On track, it feels more like 4 to 5kg lighter than the 2013 bike, meaning the mass centralisation design program seems to have paid dividends. The 2014 YZ250F is now one of the lightest bikes to flick from side-to-side through chicane-style corners, and in the air, it takes very little rider input to change its trajectory. And, like the Suzuki, Honda and Kawasaki, it requires bugger-all rider input into the pegs and bars to change lines mid-corner or to crank it into ruts. But what really stands out about the Yami

is how it’s gained agility without giving away the YZ-F’s trademark stability. By retaining its poise at high speeds, the new chassis gives you the confidence to push hard everywhere on the track.

For the 2014 YZ250F, Yamaha has gone with firmer spring rates but substantially lighter compression damping (for both its fork and shock). For our lighter test pilots, this created a compliant ride over small bumps, but heavier testers found the fork was firm – to the point of being harsh – in the first part of the stroke. How do we explain that apparent contradiction? Well, it soon became clear that the Yami’s fork was riding down in the firmer part of its stroke for the 85kg+ testers. And when they started pushing the limits of the Yami’s suspension over bigger jumps and braking bumps, the fork found it bump-stops. Just as they did with the Honda and KTM, most testers wound up a fair bit more compression damping on the Yamaha’s fork to improve the chassis balance through the fast downhill braking zones. Which definitely worked. After all, four of the six test riders posted their fastest lap aboard the Yami. But it’s clear that Yami’s 48mm Kayaba will benefit from some revalving to help it ride up in the plusher part of its stroke.

POWERPLANT

The five-valve engine used in the YZ250F for more than a decade has given way to a four-valve, fuel-injected powerplant with the same reverse-oriented cylinder, Keihin EFI system and wet-sump lubrication system as the YZ450F. The new 250cc engine also gets different inlet and exhaust ports, cams, ECU, crankshaft, transmission and clutch, and an all-new two-ring forged piston.

CENTRALISATION

The bilateral beam alloy frame is more compact for 2014 and designed to accommodate the all-new fuel-injected engine. The subframe is shorter and lighter to match the new frame and muffler, and the air filter is relocated to above the engine to suit the new inlet tract. To improve handling via ‘mass centralisation’, Yamaha has focused on moving all the major components away from their extremities.

FUEL TANK

For 2014, the bigger (7.5 litre) fuel tank has been moved backwards and down to centralise mass, and this has allowed more volume on the throttle body side of the air filter (which pays throttle response dividends). To improve access for maintenance, the longer fuel line and fuel pump harness allow the tank to be spun 180º and placed on the subframe.

SCORECARD

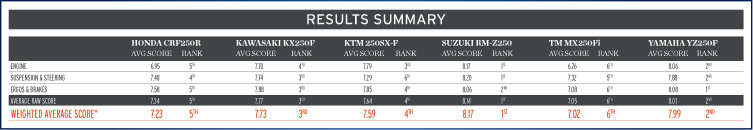

THE VERDICT

Before we even collated the scores, it became pretty obvious that this year’s 250cc MX shootout winner would come from one of three bikes – the Suzuki, Yamaha or Kawasaki – because a greater majority of test riders repeatedly singled out these machines as the best performers and the hardest to fault.

Being ‘hard to fault’ is largely why the KX250F has taken shootout honours in recent years. But doing everything well and nothing badly didn’t quite cut it this year; not when both Yamaha and Suzuki have stepped their games up so significantly. This year, a winner would be a bike that did everything brilliantly and nothing badly.

And that is a fitting description for the Suzuki’s 2014 RM-Z250. Aside from the fact the RM-Z250 steers with noticeably more precision and confidence than its rivals, it also has the torquiest and most tractable power; the best suspension package; and the most universally agreeable ergos. But the real magic of the Suzuki is how well its chassis, ergos and power all complement each other. And when all facets of a bike work in such perfect harmony, it makes riding the thing so much more effortless and enjoyable. Which, at the end of the day, is what we’re all here for.

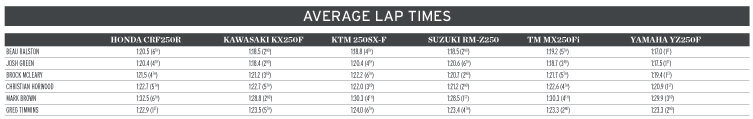

AVERAGE LAP TIMES

RIDER FEEDBACK

PRO: BEAU RALSTON – 23, 187CM, 88KG

“For me, it’s a toss-up between the Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha. The Yami has heaps of power and hits hard, and what racer doesn’t like that? I loved the Suzuki’s torquey power and how well it turned. The Kawasaki is kind of a mixture of those two – it doesn’t hit as hard as the Yamaha or quite have the torque of the Suzuki, but its all-round engine and well-balanced suspension package is impossible to fault. It’s really tough to make a call, but if I could only take home one bike, I’d take the … Kawasaki or Suzuki. Okay, put Kawi’s higher-bend bars on the Suzuki and I’d take the RM-Z. I’m taller than average and like a spacious cockpit.”

PRO: JOSH GREEN – 23, 180CM, 80KG

“Power is always important for small-bore bikes, and the Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki powerplants were the standouts for me. Sure, racers are going to fit an aftermarket pipe, but out of the box, those three are closest to being race-ready. From a handling perspective, I liked the agility of the Suzuki, Yamaha and Honda. The Suzuki has the best fork and turns better than any other bike, but the Yamaha is more stable at speed. The Suzuki is the pick of the bunch for tight tracks, but the Yamaha rules around faster tracks and where there’s good traction. If I had to buy one, it’d be the Suzi or Yami. It would come down to who gave me the best price.”

JNR PRO: BROCK McLEARY – 16, 172CM, 62KG

“I’ve raced KTMs for years so I was comfortable aboard it. But in standard trim, the Kato was way too firm for me and the gearing was too tall. After riding all the bikes at the beginning and end of the day – when the track was at its best and worst – the choice was pretty clear for me: Yamaha or Suzuki. If you’re on a track with lots of traction, the Yamaha’s instant power makes it the pick of the bunch. If you’re on hardpack, the Suzuki’s torquey power and awesome steering put you in control of the bike, rather than the bike being in control of you. To me, these two bikes were above the other four machines by a fair bit.”

EX-PRO: CHRISTIAN HORWOOD – 36, 183CM, 74KG

“It impressed me how good all six bikes are and how that, with a few little tweaks, they’d all be as competitive as each other. I think the lap times proved most of us were playing with fractions. But for me, the choice is between three bikes. I felt really at home on the Suzuki from lap one. I liked its fork, how it steered and the suspension action on the RM-Z. I was quickest on the Yamaha, but I set that lap time when I was freshest. And I was most comfortable aboard the KTM, which I’ve raced for years. The Kawasaki isn’t far off them. And the Honda … well, with its restricted exhaust, it’s hard to know how it stacks up.”

VET: MARK BROWN – 35, 169CM, 67KG

“It’s easy for me – I’d take the Suzuki, even if I had to pay full freight for it. The Yamaha, Kawasaki and even the KTM are all close, but the RM-Z constantly made me feel like the track was freshly prepped and that I had a brand new set of tyres on the thing. It just turns that much better than the other five bikes, and that gave me so much confidence to push. It was unbelievably forgiving and predictable in

all sorts of terrain. Aside from the fact the RM-Z250 has got the torquiest and easiest-to-use power, best-feeling

front-end and perfect ergos, I found I could get aggressive and throw it around as soon as I jumped on that bike.”

MASTER: GREG TIMMINS – 40, 175CM, 95KG

“I was quickest on the Honda, but I really didn’t feel quick aboard it. To race the CRF, it’d need an aftermarket pipe and an oversize front disc, but I do think it’s got a lot of potential. The Honda’s a fair bit cheaper than the other bikes, which gives you room to customise it, and its quality of finish and resale value is always good. The Yamaha, Kawasaki and KTM are all very strong packages, but I

really can’t look past the Suzuki. For me, it had the best motor, the best fork, the best brakes, the best chassis balance and the best suspension action. I could race the Suzuki out of the box; it wouldn’t even need a pipe.”

Be the first to comment...