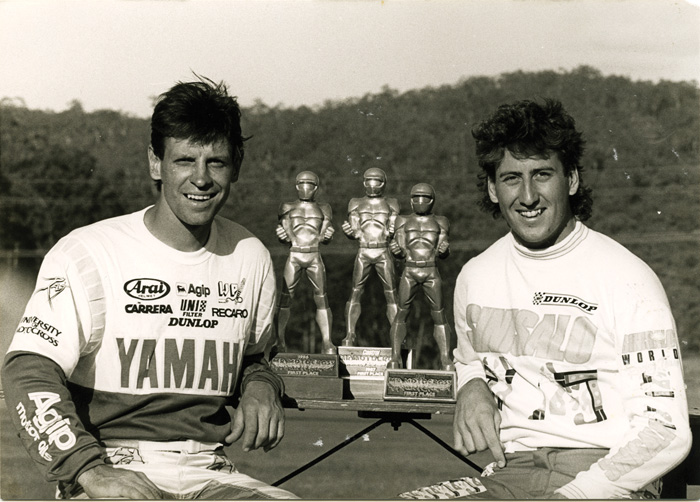

Dack vs Bell – An Intense Rivalry!

Craig Dack and Glen Bell rode together in their teens, then faced off for national titles as men, and drove each other to all-new heights. The two virtually owned Australian motocross and supercross between 1986 and 1992, but they were never in the business of trading pleasantries. In fact, so intense was their rivalry that the obsession to beat each other almost cost them title wins. Some 25 years later – in a compelling feature article that first appeared in the March-April 2015 issue (#49) of Transmoto Magazine – we asked an older, wiser and less intense Dack and Bell to reflect on what many believe was one of the sport’s all-time greatest rivalries…

If you want to pick a fight among old throttle twisters at a party, ask them when the ‘boom time’ of Australian motocross was. Many will swear black and blue that it was the 1970s; when the gods of Mister Motocross – the Flood brothers, Anthony Gunter and Stephen Gall – were moulded out of alloy, leather and elbow scabs. But in fact, Gally won three of his four titles in the 1980s. The ’80s also saw the emergence of Jeff Leisk, the first Aussie to build a successful international motocross career (after belting up everybody in Oz in ’84 and ’85, that is!). And the first time people could watch dirt bikes racing from a plush seat in the Melbourne Tennis Centre, then flick over to it the following day on Channel Nine’s Wide World of Sports … yep, that was the ’80s, too. All the 1980s really needed was for the next two titans of Australian motocross to lock horns for a decade. Well, you guessed it, the ’80s also delivered that story line. It came in the form of Craig Dack and Glen Bell.

THE COMBATANTS EMERGE

In 1985, it had been a couple of seasons since the most famous name in Australian motocross, Stephen Gall, had won the last of his four Mister Motocross figurines. It would have taken a brave man to suggest that to Gall at the time, because ‘Mr Yamaha’ was busting a gut trying to prove it wasn’t the case. But sadly, it was. And with Leisk taking himself off to the States in ’86, the future of the sport in Australia could be found under the Toshiba Yamaha tent.

In one corner was Craig Dack. With unsurpassed discipline and dedication, and already described as the next Stephen Gall, he’d been talent-spotted by SG himself at a Hungry Creek motocross camp years earlier. Dack was being groomed by one of Gall’s own trusted supporters and previous sponsors, John Collins. In the other corner was Glen Bell – car mechanic by trade, prodigiously talented, but so introverted that some people read him as arrogant. Bell only started racing motocross at 18, but by 20 he’d won the Australian 125cc championship. And by 21, he was riding on the official Yamaha team. Bell had been a shit-hot rising trials rider who had competed with Craig Dack’s father, Barry, but stumbled into a friendship with Craig (who rode an RM80 at the time), which prompted him to try his hand at motocross. The young Bell learned the ropes by chasing Dack, and returned the favour by driving his future teammate around (in the days before Dacka had a licence). So, you’d think the team Toshiba Yamaha tent might have been one big happy family. Well, you’d be wrong…

“I think Belly knew about Craig’s association with Stephen Gall and myself and about some of the doors that were opened for him,” said John Collins, “and I think that probably motivated Belly to go harder.”

“It’s hard to explain,” says Dack. “We started out riding for fun as mates, but it all changed very quickly; it soon ended up with me in the blue corner and him in the red corner.

And to be completely honest, I felt that for the past couple of years, I’d helped him get up to speed quicker than he should have, and suddenly he was a threat. I’m sure that, at the same time, his instincts also changed. It’s not that I hated him or that there was any anger; it’s just that we’d become competitors, and it was a different world.”

“Some riders found it much easier to have an adversarial relationship with an opponent, rather than a convivial one, and Dack freely admits he was one of them.”

“Craig was like Gally’s protégé,” says Bell, reflecting on those early years. “They spent a lot of time together, but I just did my own thing. I won the 125cc Gold Cup and Australian 125cc Championship ahead of Craig in 1983, and I started winning supercross races before Craig did, too. So I think that’s where some of that friction started.”

Although they were running under the same team banner, a rivalry that would come to define a sport for almost a decade was well underway.

OPPOSING BACKGROUNDS

Trials wasn’t a common motocross training tool back in the 1980s, but it’s a wonder, because Bell seemed to gain an uncannily fast springboard to top-level motocross and, more particularly, supercross. People speculated as to whether it was trials’ demand for super-sharp clutch and throttle control, or the fine standing balance, or simply Bell’s talent and determination.

“To start motocross at 18 is unheard of,” says Bell’s long-time manager, Mark Luksich, “but Glen just went and did it and adjusted really quickly. By contrast to Craig Dack, who had a more flowing style, Glen was a very muscular rider who placed plenty of emphasis on gym training and strength. He had an enormous amount of talent. He won 12 Australian MX/SX Championships, and was probably the best supercross rider that Australia ever saw – apart from Anthony Gobert and Chad Reed. Belly won 76 Supercross finals in Australia, a stat that’s unlikely to ever be replicated,” Luksich goes on to explain.

“Coming from trials, I had a different style,” says Bell. “Jimmy Ellis for example, who started riding in the ’70s, hardly took his bum off the seat. But people would say to me, ‘Gee, you stand up a lot’.”

They probably said it a lot more the day Bell shared a YZ490 with Paul Caslick at the infamous Nepean 6-Hour race, and could be seen standing up into the braking areas – on a speedway track!

“I’m sure Glen benefited from riding with me early on,” says Dack, “Initially, I was always quicker than him, but he was progressing very fast. I think those trials skills helped him adapt to supercross quicker than I did. Back then, supercross wasn’t part of a rider’s DNA like it is now. It was in its infant stages, and we all had to adapt to it.”

“Glen Bell only started racing motocross at 18, but by 20 he’d won the Australian 125cc championship. And by 21, he was riding on the official Yamaha team!”

While Glen Bell had Craig Dack to chase, Dacka had Stephen Gall. And for an impressionable kid trying to learn how to be successful at motocross, role models didn’t get a lot better.

“Gally certainly had an influence on me right from early on,” concedes Dack. “We started becoming friends, which was surreal for me at the time, because this was a guy I used to go watch win Mister Motocross. Everything that we did back then, we used to turn it into a competition. It could be anything, but it always revolved around something physical. For example, if you said the word can’t on a particular day, you’d have to do 50 push-ups. Gally was really into the fitness side of things, and that’s the area I got the most insights from him. But we drove each other, and I feel like I kept his career going a little bit longer. And he certainly helped me get the ride with Brian Collins Motorcycles.”

Gally knew exactly what he liked about Craig Dack. “In all the important aspects of being a professional rider,” says Gall, “Craig was very, very dedicated. He moved from his parents’ house at Blacktown my friend’s place (David Hirsch, who passed away a few years ago) and he just lived and breathed motorcycle racing. He rode and trained with me all the time, and I could see him elevating his training and his intensity. And that’s why I referred him to John Collins.”

While Dack clicked with Gally as far as the training side went, it was Collins who taught Gall’s protégé the business side of the sport and how to carry himself in public. “At the time, I didn’t really realise John was in effect my mentor,” says Dack, “but he definitely had a big influence on me when it came to psychology and the commercial side of what I was doing.”

“In one corner of the Yamaha tent was Craig Dack – a bloke with unsurpassed discipline and dedication, and already described as the next Stephen Gall. In the other was Glen Bell – car mechanic by trade, prodigiously talented, but very introverted.”

COMETH THE HOUR

By 1986, these two up-and-comers had become lead riders. Glen Bell rode the new Yamaha YZ250S, resplendent in the same fluoro orange Marlboro colour scheme as the 500cc GP bikes. It soon became apparent that a high-quality paint finish and the constant machine-gunning of roost didn’t go hand-in-hand, and Belly spent a lot of his training time painting bikes that year. One thing Bell never noticed, though, was the pressure of being a number-one rider.

“I was oblivious to that,” said Bell, “because, no matter how much pressure anybody else applied, my own motivation to win outweighed it.”

Indeed, Bell was intense; intent on perfection and very hard on himself. “People wondered how a quiet, unassuming bloke could win races and be so aggressive on the track,” he says. “They thought that as soon as I put the helmet on, something must click inside of me. But that wasn’t it. You can still have a gentle nature and respect people, but if you have the determination to do something, no matter what it takes to do it, you can push yourself physically and mentally to whatever the level of your competition is.”

Unfortunately for Bell, his competition was about to turn the move to Honda into two Mister Motocross series wins. “I was a pretty strong runner-up to Jeff Leisk in 1985,” says Dack. “At the time, there was a changing of the guard, where Gally and a few of the other guys were on the way down, and once I signed for Honda and moved down to Victoria and changed my whole life, it was like a switch flipped over and I decided that I was the man.”

Along with teammate David Armstrong, Dack’s move to Victoria marked the beginning of a relationship with the highly respected crew chief, Gary Benn – a relationship that has lasted almost 30 years, and counting. But it wasn’t always all rainbows and unicorns with Benn. “Gary was old-school harsh, and having just moved away from home to stay with him and his wife, Hanny, I struggled with that at times,” admits Dack, before launching into an anecdote to illustrate the point: “I vividly recall a really muddy Mister Motocross race at Broadford. With Belly’s trials throttle control and ability to ride around on the footpegs, he was really good in those conditions. Broadford is like gorilla snot when it’s muddy and I struggled to the point where, in the last moto of the day, I just couldn’t get it together. And for the first time in my life, I actually threw the towel in and rode back to the pits. It was the worst feeling I’ve ever had in my life. I was sitting there with my head on the handlebars, feeling lower than a snake’s belly, and the first thing Gary said was, ‘I thought you had more in you than that, Dacka,’ before walking off. I get the psychology of that. But I just felt that, at that point, a bit of sympathy could have been better.”

At least Dack’s relationship with his new teammate was going swimmingly. Queenslander David Armstrong was the only person, apart from Gally, who Dacka was ever happy to share his training and riding with during the week. Which was fortunate, because at that point they pretty much only had each other for company.

“He was surprisingly fit, old Army,” recalls Dack. “His nickname was Party Boy, but he was always fairly strong when we ran together. I remember Honda gave us both Civics to get around in, and we used to take off and go away for days on end riding new tracks and different places. We didn’t have any family or friends in Victoria, so pretty much all we did was rode and trained. That was the best year of my career, I reckon.”

“Dacky was good at training,” says Armstrong. “I probably hadn’t trained as hard as I needed to, so I learned a lot from him that year. He was a good bloke and we got on well. It’s kind of a shame, because we seldom catch up these days. I’ll just see him at a race in Queensland and say g’day. We’ve gone in different directions. I’m married with three kids, and he’s running a race team. And I wouldn’t swap that for the world.”

CHANGING PLACES

With the dollars diving in the sport, the next significant relationship shift came in 1988 when Craig Dack and Glen Bell swapped brands – Bell to a financially tight Honda team structure created by manager, Mark Luksich; Dack to a privateer Yamaha set-up under a familiar banner, Brian Collins Yamaha.

“Honda gave us three bikes and five grand,” reflects Luksich. “It was kind of a joke, really. Even today, I don’t know what made me even do that, but Glen supported it.”

But Bell rates that 1988 CR250RJ as his favourite race bike. “As soon as I got on my first Honda, I just felt so much more confident,” says Belly (and he must mean it, because he stayed with Honda until the end of his professional career, and still maintains a relationship with the manufacturer to this day). It was at this point that Bell became his own mechanic – right down to valving his own suspension. That’s not as weird as it seems because Belly was always a mechanic who raced a motorbike, so combining the two probably enhanced his understanding of how to use the machine.

“When you know how a bike should run, it’s such an advantage to have them running well – especially with a two-stroke. They drove off the line a lot better, and it was just crucial to starts. And the difference between tuning them for day and night conditions is huge,” he says. “Some said I was obsessive-compulsive, but it’s the way I like a bike to be.”

Dack’s return to Yamaha yielded a third consecutive Mr Motocross title, and then, after a year in Europe in 1989 (when the Mister Motocross took a year’s hiatus), a record-equalling fourth in 1990. It was the resumption of a relationship that would ultimately evolve post-retirement into team ownership and management. It was also the resumption of another less positive relationship for Dack; with Yamaha’s YZ490. “I still have nightmares about those things. I hear one start and I get the heebie-jeebies,” says Dack, with a laugh. “Physically, I was pretty slow developing, and I remember flapping off those things like a wet rag in the breeze for years. They bit me so many times, and I was happy to see the back of them.”

A COMMON CAUSE

While Dack and Bell might have been bitterest of rivals for the entire domestic season, all that changed when they pulled on the green and gold for their many Motocross des Nations appearances.

“Together, Glen and I represented Australia at the MX des Nations for six or seven years,” says Dack. “And if you talk to any rider who’s been part of it, I think they’d say the same thing. All year long, you would bash each other’s brains out, but at the des Nations you became mates again. We had some really fun times there; we’d stay back in Europe for a few days and have a bit of a holiday. They’re the nice things I remember about the past with Belly. Then we’d come back home and be full-on rivals again.”

The pair, generally with Bell riding a 125 and Dack on a 250, rode for Aussie teams that achieved some of our best results, including (teamed with Jeff Leisk) the historic fourth Overall in France in 1988 – a result that remained Australia’s best MXoN result for almost 25 years.

“It’s not that I hated Glen or that there was any anger; it’s just that we’d become competitors, and it was a different world.” – Craig Dack

TURF WARS

The solidarity of the MXdN trips, however, was soon forgotten back on home soil. “The rivalry between Craig and Glen was there all the time,” says Luksich. “Craig was the only guy Glen cared about. For so much of the years Glen and I worked together, all we had to do was beat Craig.”

And it was similar at the blue end of the pit, according to John Collins. “They were both from Sydney, both very good, and they were always fierce rivals,” says Collins. “There were 30 guys on the start line, but for Craig and Glen, 28 of them didn’t matter for a majority of the time. If Dacky didn’t win, what mattered more was that Belly was behind him.”

Some riders found it much easier to have an adversarial relationship with an opponent, rather than a convivial one, and Dack freely admits he was one of them.

“I say to my riders these days, you haven’t got to be an arsehole to everybody, but you’ve got a responsibility to all the sponsors to go and win them some races. That’s what I was getting paid to do back in my time, and I just felt that if I was too friendly, I couldn’t do that job properly.”

But just how ‘adversarial’ did the relationship with Belly get? “I had no problem diving into a corner and pushing him or running over his foot,” admits Dack. “That’s just how you did it back then. And if I did that, I’m sure he would have been angry. But I’m sure there would have been that level of respect, where the reaction was, ‘Okay, I’ll get Dack back next time’. And that’s how I felt about him. I probably got angrier with lesser riders and I remember abusing some for the stupid things they did.”

You can still have a gentle nature and respect people, but if you have the determination to do something, you can push yourself physically and mentally to whatever the level of your competition is.” – Glen Bell

ON REFLECTION

If you ask both riders about their standout races, Dack mentions his spectacular ’86 MX des Nations 250 ride in Maggiora, Italy, while Belly speaks of his fifth-place finish in the 1989 Tokyo Supercross (against the full might of US factory riders) or beating Jeff Leisk in the first moto of the 1988 Australian 500cc MX Championship at Gum Valley (right after the Leisk had just won the US GP, and on the eve of his departure to the Grand Prix scene in Europe). But, despite their long-standing rivalry, Dack makes no reference to races when he beat Bell, nor vice-versa. Curious! As Dack puts it, somewhat paradoxically: “We’ve never not been friends; we just didn’t talk. But late last year, we were both up at Gladstone for the MX Nats round, and so was [Supercross Masters promoter] Phil Christensen and Mark Luksich, his old manager, and we all went out to dinner. It was really nice.”

Bell appears to think much the same way. “I get along fine with Craig. I don’t hold any grudges against anyone. What happened is what happened; I understand that.”

Perhaps the final word should go to Mark Luksich, who worked closely with Bell for years and now, in his role as Motorcycling Australia’s Motocross Commissioner, comes into frequent contact with Dack. “I’m not sure they’ll appreciate me saying this,” says Luksich, “but I don’t know whether there is a huge difference in their personalities. I spend a lot of time with Craig now, with what I do with the sport, and it’s funny, I see a lot of Glen in him. All I know is, during that period some 30 years ago, there was no love there. Plenty of respect. But no love.”

DAVE ARMSTRONG, ON DACK & BELL

During his first year with Honda in 1986, Craig Dack claimed the first of his four Mister Motocross titles. But in 1987, Dack’s title defence was no walk in the park. In fact, Dack’s former Honda teammate, David Armstrong – who’d signed on as Kawasaki’s lead rider – would prove to be his biggest title threat. “Army” actually led the series fleetingly, until misfortune intervened.

“Three-quarters of the 1987 series was fantastic for me,” recalls Armstrong. “Dacky will probably never agree with this, but I believe I had a real shot at winning Mister Motocross that year. Toward the end of the season, Craig had crashed with someone else in the first turn of the first moto at Gillman. I then came along, and there’s this bizarre photo in one of the magazines of his head under my bike, and my front wheel fully locked sideways trying to avoid him. Unfortunately, it knocked him silly. I came from last up to second in that moto, and took the series lead. Then in the next race, I crashed out when a guy fell in front of me, and I screwed my shoulder. Craig came back and won the next three motos, even though he was terribly injured and could hardly walk. These days, they wouldn’t have even let him ride because there’s no way he wasn’t concussed. Anyway, had I been able to ride, I would have had his measure, but I was out for the day. It just goes to show the sort of fierce competitor Dacka was. Most normal people would have just pulled out, but he was one strong-arse, determined rider. I saw that work ethic first-hand the previous year when we were teammates. Dack and Bell were both fierce competitors. They were miles apart, yet similar. They both had that never-say-die approach and on-track aggression. If either one of them was looking to put a pass on me, I knew I was in for it!”

More In This Series

Be the first to comment...