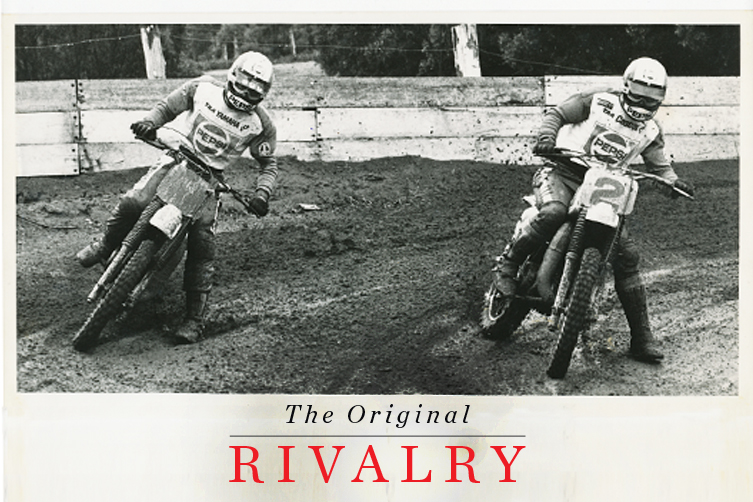

The Original Moto Rivalry: Gall vs Gunter

Back in the in the late 1970s – in the glory days of Australian Motocross – you were either a Suzuki fan or a Yamaha fan; an Anthony Gunter fan or a Stephen Gall fan.

From 1976 to 1982, Anthony Gunter and Stephen Gall had a stranglehold on the infamous Mister MX series, and the fierceness of their rivalry consumed the motocross world. Three decades on – in an article that first appeared in the July-August 2014 issue (#45) of Transmoto Magazine – we got these two legends back together to relive the glory days and to reflect on the gulf between the reality and public perception of their acrimonious relationship … on and off the track. This feature article – cleverly crafted by Transmoto contributor, John Pinnell – attracted so much feedback a few years back, we thought it’d be fitting to re-run in the lead-up to the 2018 MX Nationals.

Sure, much of their legacy was captured in monochrome, but Anthony Gunter and Stephen Gall – the two Alpha Males of Mister Motocross’ most successful era – brought colour and excitement to the sport like no one else. Their rivalry may have appeared jovial on the surface, but in reality, they both wanted the title more than they needed their next breath. The only question is: how’d they not kill each other?

“As a kid racing in Juniors, you weren’t exposed to those levels, but once you were competing with guys who were trying to make a living off it, it was a different ball game.” – Jeff Leisk

The Mister Motocross series in the late ’70s was something else. It was the dynamite behind a sport in explosion. The series was radical, edgy, dangerous and evolving fast – just like the sport itself. Leather pants, fireman boots and rugby jerseys were giving way to nylons, Bell Moto Star helmets and Golden Breed and Tycon jerseys that came emblazoned with the names of mainstream corporate sponsors such as Pepsi and department store, Myer.

The suspension of the day was less than forgiving to say the least, and it sent you rushing for your kidney belt. Two-stroke powerbands were short and brutal, and the ‘accepted’ geometry for lapping a track safely at speed hadn’t yet been accepted. But hey, if you didn’t ‘come-a-gutsa’ occasionally, you were probably ‘riding like a sheila’ anyway.

Next came the fans – thousands of ’em. Amaroo Park, west of Sydney, would pack anywhere from 8000-12,000 long-haired, bell-bottom jean (or stubbies) wearing, pre-fast food body-fat-leveled, cheering, knowledgeable fans. In places like Clarendon in South Australia, the line-up of cars parked down the road stretched for kilometers – sorry, miles – and when you could get no closer, you took Shanks’ Pony the rest of the way. Bad luck if you blew a thong.

“It showed me that in the pits we were all friends, but once the gate drops with professional riders it’s all business and Gally, he was just a machine.” – Bryan Fleming

The best way to encapsulate these glory days is: warfare! It was motorised, publicised, sometimes televised and above all else, tribalised. Not a unique concept in V8 terms, but back in ’78/’79, a Mister Motocross fan was probably either a Suzuki fan or a Yamaha fan; a Gunter fan or a Gall fan.

The fans, those with Castrol Super TT still in their veins, remember it like it was yesterday. Maybe not all the facts, but the way it made them feel.

“I was only in Juniors,” says Jon Fowler, a passionate supporter of the series. “I’d had the YZ C model, but the following year bought the Suzuki. It didn’t matter, though. I always cheered for Gall. To me he was … [he thinks carefully about it] the good guy. It’s funny. I remember him wearing white more often, and, well … to me, the guy in the Mister Motocross poster seemed to resemble him [laughs].”

“Gunter, on the other hand, I only ever saw from a distance. He was usually a lot more low-key,” he goes on to say. “Suzuki had been the dominant force of the era, and while Honda and Kawi had a few goes at catching up, to me there was Gall and Gunter, and then the rest. I still remember getting the shits when Gunter would get one over Gally. I wanted to go home and burn my Suzuki to get back at him [laughs].”

Suzuki’s hero, Anthony Gunter, was an introverted kid from Wollongong, a city known for its coal mining and steel industry, as well as for a line-up of well-known surf beaches. But it wasn’t the latter which attracted the young Gunter, who grew up belting around on a BSA Bantam, intent on following his brother’s footsteps into racing. “I did some schoolboy sporting trials and rode at Mt. Kembla every chance I got. Man, we rode some old shitters back then,” says Gunter. “I look at some of the 85s and 65s that dads go home from the shop with nowadays and think, ‘Wow, how good would that have been as a kid?’At the time, you couldn’t race until you were 17 years old because of the Speedways Act, but Gunter still sneaked into the odd club day now and then.

His quiet, casual stance, golden surfie locks and long fringe belied the creature lurking inside. Only the intensity and focus in his chocolate-brown eyes hinted at the career trajectory Anthony Gunter was about to chart.

“I started racing in ’74 and actually won the New South Wales 125cc title that year. I can’t really remember much about ’75 other than that I rode one Mr Motocross round at Amaroo, cartwheeled the thing and chipped some vertebra in my neck.”

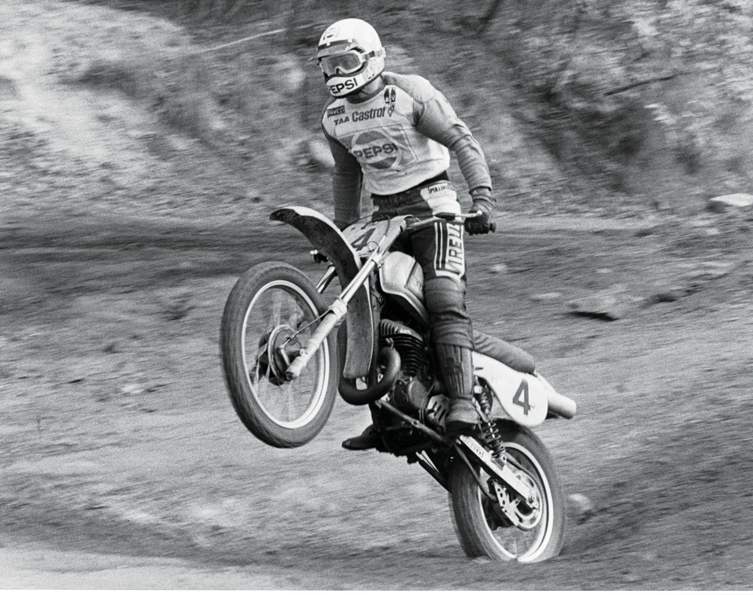

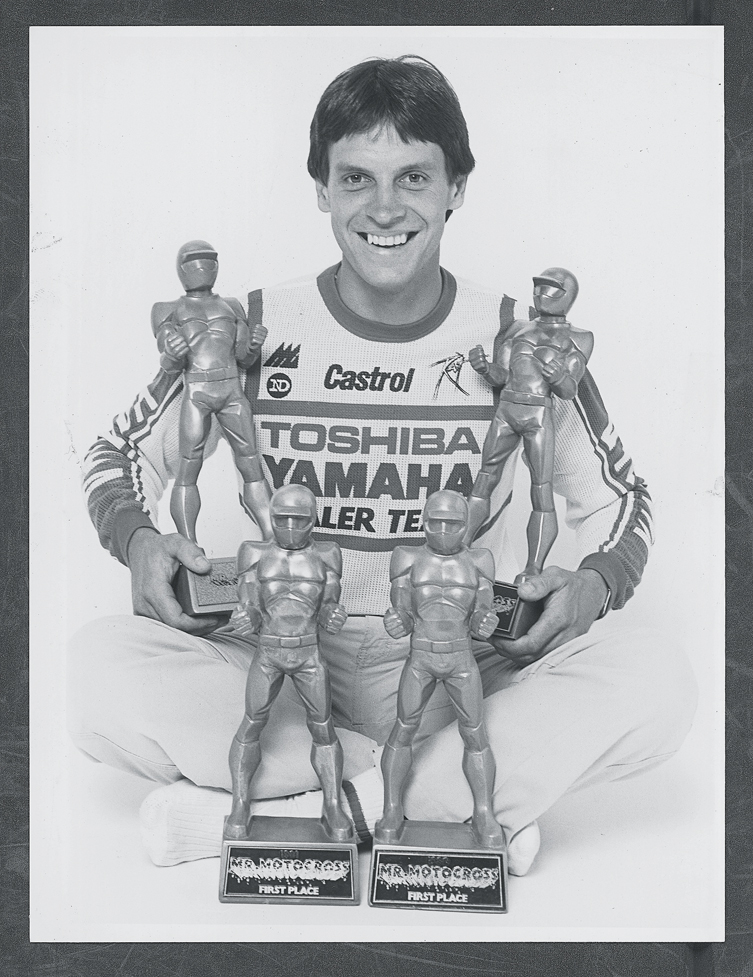

^ ‘Grunt’ as he was known to his peers, wheelies his factory Suzuki to victory in the 1979 series final.

By 1979, his sixth year of competition, Gunter had been at the top for four years. He’d won Mister Motocross in 1976, successfully defended it in ’77, lost it in ’78, and was about to win it back again. Not bad for a 22-year-old.

Gunter had the goods alright, and there was no doubt that getting on top of him would take some audacity. Another word for which is … Gall.

Sydney boy, Stephen Gall, Gunter’s chief rival of the era, was no Junior racing prodigy, either. Gall’s understanding of, and thirst for, speed was developed riding bikes and driving go-karts with his brother, Dean, around his parents’ farm at Menai where they raised Shetland Ponies with, presumably, very

high-stress levels.

Nobody really knew exactly who Stephen Gall was until the late Geoff Eldridge put him on the cover of the first issue of ADB in 1975, spectacularly cranked over on his YZ. But, boy, was that about to change! In 1975, Gall attended the last round of Mister Motocross and, as a lowly C-grader, came eighth Overall. From the next year on, he would finish in the top four of Mister Motocross for 10 years straight, winning the coveted statue in ’78, ’80, ’81 and ’82.

By the end of his long career, Gall had become not only the most successful Aussie dirt bike racer, but the best-known, and the guy generally considered to be the sport’s first true professional – not simply in the financial sense, but in every sense. Gall carefully grew his public image, his relationships with the media and sponsors (he’s closing in on an unbroken 40-year relationship with Yamaha), his presentation, all aspects of his technique, his fitness, his flexibility, nutrition and psychology. If it yielded a better performance, Gall studied it, and then applied it.

^ Stephen Gall inducts Anthony Gunter into the ADB Hall of Fame back in 2008.

Interestingly, the things that really define who Stephen Gall was, stemmed mainly from who he wasn’t. He was never the most gifted guy out there, but one gift he did have was the preparedness to work hard and meticulously for what he wanted, and keep working at it. Even today, normal Aussie blokes don’t like to stand too close to him because the embarrassment is too much to take. At 56, he’s still sporting a six-pack, and is three times fitter than most of us have ever been in our lives!

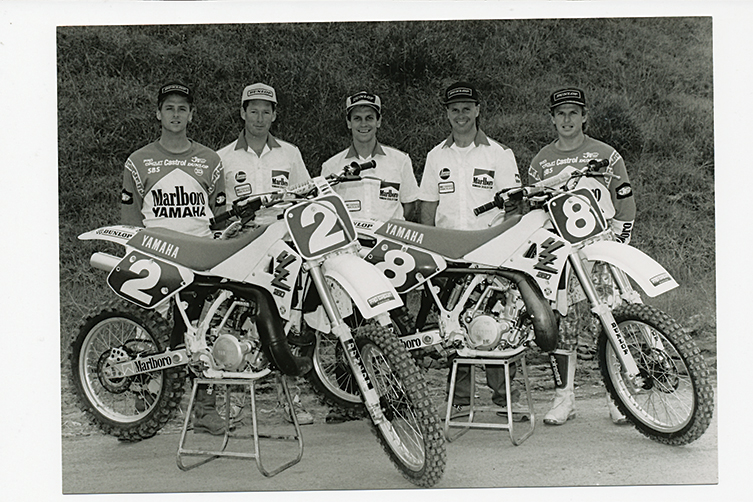

The ’84/’85 Mister Motocross champ, Jeff Leisk, got to spend time with both Gunter and Gall as a Junior; back in ’79, when the pair stayed with Leisk’s family at Newport Beach, USA, in a house his dad rented. Leisk got to ride with them at the legendary Saddleback Park and gained an insight into their personalities. “They were two different animals; very different in their approach,” says Leisk. “Steve didn’t have quite the natural ability that Gunter had, but he was always going to figure out a way to win, using training or diet or books to build his performance. Gunter, I think of as more like a bulldog – he was strong, aggressive, and though he trained hard, he wasn’t pedantic about it like Gally. They did have one quality in common, though; they would both run over their grandmothers to win a race. They weren’t dirty riders who traded paint on every pass, but if they had to put the hard move on, they definitely would.

^ Gunter leads Gall early in the Mister Motocross series at Canberra’s MX track in 1980.

“In my first year of Seniors,” Leisk went on to say, “I raced a supercross over here at Fremantle, and, being the young up-and-coming local prospect, I had a lot of crowd support. I remember racing against Anthony in one race and having him just completely T-bone me over the top of a berm and out of the race. It must have looked pretty hard because a few of the locals came down to the pits in order to confront him about it! But they were serious players who would do whatever it took to win a race. As a kid racing in Juniors, you weren’t exposed to those levels, but once you were competing with guys who were trying to make a living off it, it was a different ball game. The Mr Motocross title was five grand to win, plus round money, and that was at a time when six would get you a new Holden Kingswood. So the financial incentive was there. Anyway, it taught me a lesson, and I wish I’d learned a few more lessons when I was younger because I had more to learn once I got to the US, and I learned those the hard way!”

“They were two different animals – very different in their approach.” – Jeff Leisk

Bryan Fleming is one of the most talented riders Toowoomba has ever produced. He continued to race anything with two wheels with passion until a terrible spinal injury at the end of 2010, but at the Queensland Open Motocross Titles at Conondale in 1983, he went ‘to school’ as well.

“I remember being there,” Fleming recalls. “I was the number one rider on the Queensland Yamaha team with my 125, my 250 and my two 490s, and Gally was there, too; as was Trevor Williams and Leisky. I got the start and I’d led three laps, then Leisky came past no problem, and then Gally caught me. I remember coming into this first-gear, rutted corner that was nearly a hairpin, and at the last second I see another Yamaha jammed up the inside of me and I get hit so hard, I go flying off the corner. Ten minutes earlier, Gally had been giving me advice on how to set up my rear suspension! It showed me that in the pits we were all friends, but once the gate drops with professional riders, it’s all business. And Gally, he was just a machine.”

And so it was set up. Two hard bastards who expected to win. Alpha racers at the top of their game; one with the #1 plate, and the other wanting it back. On a tour to promote a round at Broadford, they would visit every newspaper through Bendigo, Ballarat, Shepparton and Albury with Mr Motocross promoter, Vince Tesoriero, like heavyweight boxers. The question was inevitable: “Are you going to beat this bloke on the weekend?” and the answer, just as invariably, was usually accompanied with a confident and steadfast gaze, “Yes, yes I am.”

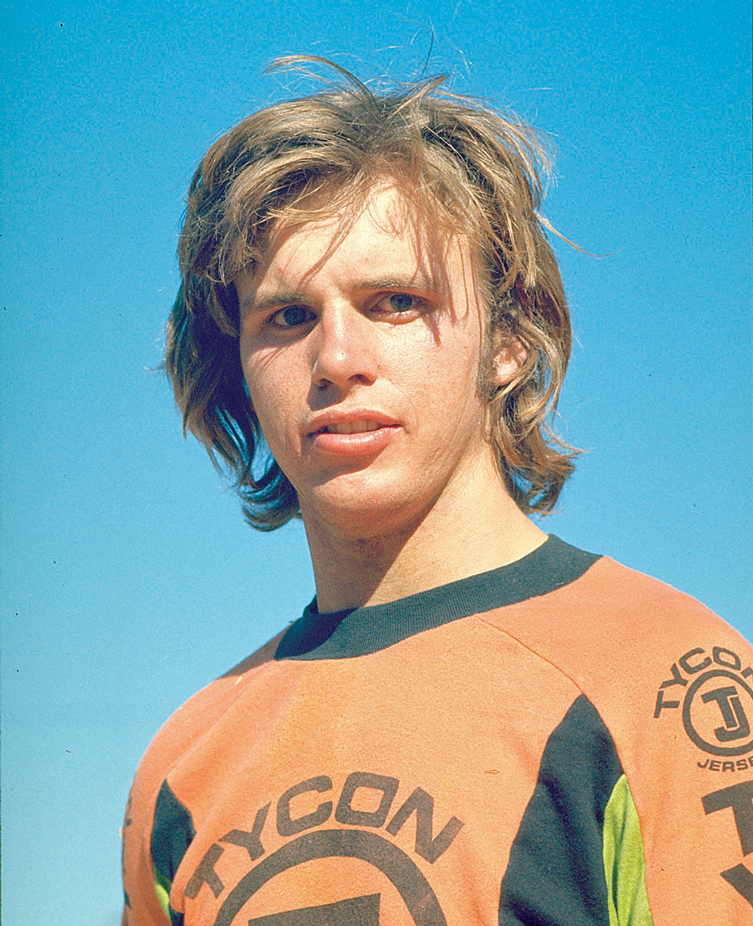

^ The trademark long-hair look of 1976, when Grunt won his first ever Mister Motocross title.

The media hungrily devoured the conflict, and Tesoriero fed them with it. Anthony Gunter remembers that time well. “Vince pushed the rivalry between myself and Steve. It became similar to the V8s, with Holden versus Ford, and people on either side. The public perception was that Stephen and I were out to do each other in. People would come away thinking, ‘These blokes are gonna f@#kin kill each other’. So, naturally, they wanted to come to the race and see what happened. It definitely got people more involved in Mister Motocross, and it got them either on my side or Steve’s.”

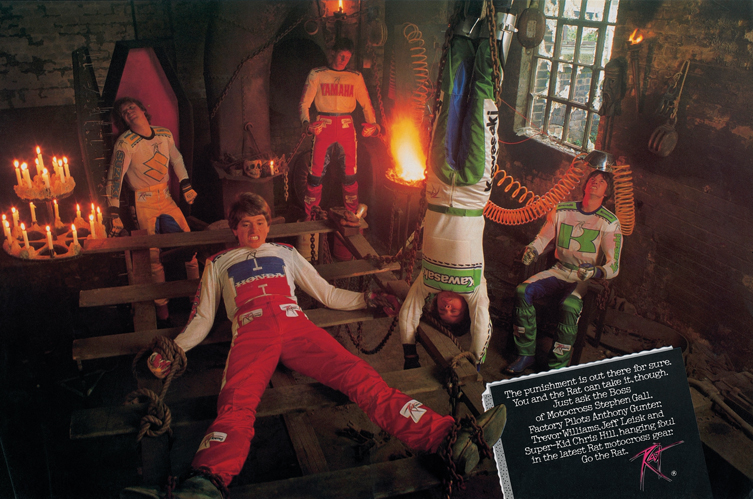

Motocross has a few legends without helmets, and Vince Tesoriero is one. Few people know just how much he helped build the riders of the day; sponsoring them or arranging sponsorships, and showing them how to grow their public profiles. And with his background in advertising agencies and marketing, he didn’t see any mystery in how to go about promoting Mister Motocross.

“Vince would promote two riders like they were prize fighters in a boxing match,” remembers Craig Dack, the series’ only other four-time winner. “We don’t have that today and I think the sport lacks that same essence because we don’t promote those rivalries. We need to start doing that again.”

Gall agrees: “Yeah, we definitely played that up. Because being around Vince, who was the consummate promoter, you get to learn a lot, and he did teach me quite a bit back in those days about making the whole series work. We knew that if we played up that whole competitive aspect, his series would go better, and ultimately, that meant the riders may get more money, too.”

“Stephen took to the publicity side of things like a duck to water,” said Tesoriero. “It was a lot harder to get Anthony to come out of his shell initially, but I think carting the two of them around together, they learned a lot off each other, and we were very determined to make rivals out of them – simply because it was good for business.”

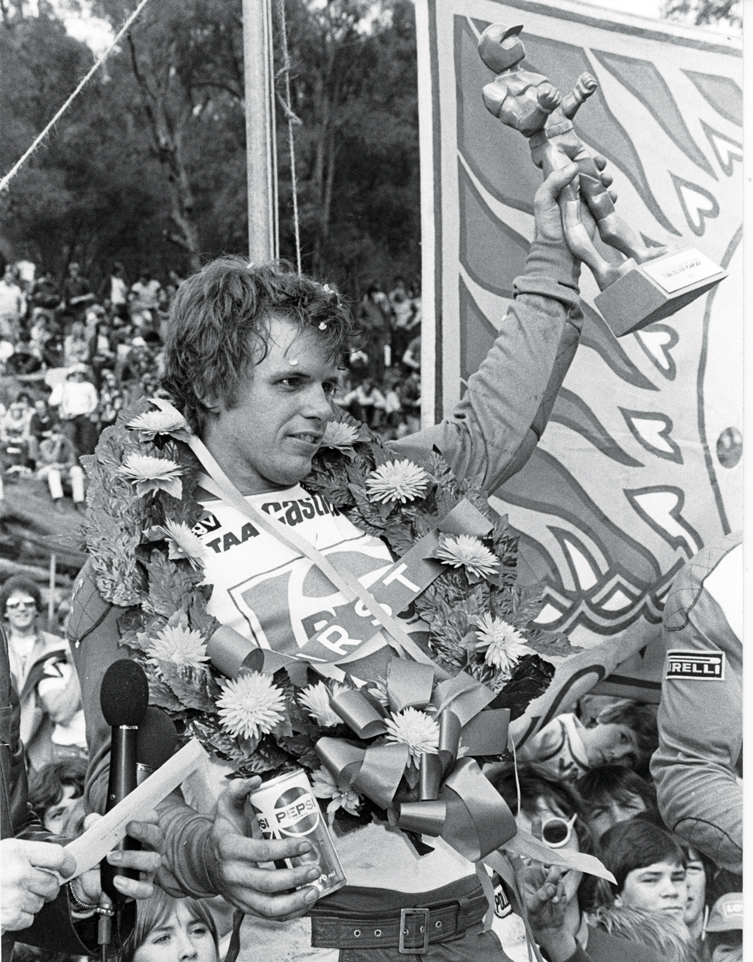

^ Gunter holds up the prestigious Mister Motocross trophy after a come-from-behind victory in the final round at Amaroo Park in ‘79.

Tesoriero would pick them both up on the Monday prior to a race for a publicity tour and they’d spend three or four days crossing the countryside in his Peugeot 504, eating together, sharing hotel rooms, etc, then, at the track on press day, suddenly they were seen as rivals again, and people got the impression they didn’t like each other.

And that was the perception. The reality, however, was that they were mates. They practiced together, spent off-season time jet-skiing together and even travelled together to Noumea and Tahiti to race.

“In ’78, Anthony and I were both Pepsi boys and we were both promoted to race dirt track events in the same Pepsi leathers,” says Gall. “The racing was fierce between the sliders and the motocross bikes; taking different lines, meeting in the corners on different lines, arguments in the pits a little bit and Grunt and I standing together as motocrossers versus the dirt trackers. So that helped bond us a little bit in the early days, too.”

But did that mean they backed off on each other? Yeah, right! “Gally was a hard competitor and I think he probably thought the same about me,” says Gunter. “We had some ding-dong battles over the years, that’s for sure. And it didn’t matter that we were mates. Once we were on the track, if I left a hole, Gally would have his front wheel jammed underneath me, and vice versa.”

“I respected Anthony for his talent,” says Gall, “and I’m sure he respected my ability at the time, so we just got on with racing and did the best we could under the conditions that were there. I think because we were friends, we didn’t get under each other’s skin as you might with someone who you didn’t have as much love and respect for.”

In 2014, Gally’s response to the idea that other riders might have thought of him as ‘firm-handed’ meets with surprise. “I had a conversation with Trevor Williams, who was one of my main competitors in the same era as Anthony, and he said to me, ‘You were aggressive on the track; you never gave an inch’. And yes, I might have been aggressive, but I never ever meant to take Trevor out, or hit him. But because I wanted to win, when the flag went across my face, I did things I didn’t ever intend to, just because I had a fierce competitive nature. Deep down, I’m not like that. I’ve got nothing against anyone.”

“I wanted to win, when the flag went across my face, I did things I didn’t ever intend to do.” – Stephen Gall

^ Gunter leads Gall down the back straight of Sydney’s Amaroo Park MX track with Kiwi rider, Ivan Millar, in hot pursuit.

Thirty-five years later, the fact the fans of the day can still recall with such passion the exploits of a couple of long-haired throttle jockeys suggests these two men achieved much more than what’s accounted for by seven trophies. What they did left an indelible mark on people’s lives.

“These days, I still get people coming into the shop, and reliving the glory days of Mr Motocross,” says Gunter. “I had a guy come in only last week, and he was yakking away about KTMs and this, that and the other. When he saw my three RMs up the back, he said, ‘I used to have a couple of those. I used to go up to Mount Kembla and I used to watch Anthony Gunter thrashing around. He was unreal’. I looked at him with a smirk and said, ‘Oh, yeah? That’s me!’ And he goes, ‘Oh, f@#k off! Is it really?’ He wouldn’t let me go back to work after that [laughs]. But it is flattering that people still remember me after all this time.”

^ In March, 2014, Rosco Holden organised a reunion of 600 people from the Mister Motocross era. On stage here is the ‘74 to ‘79 winners: Trevor and Gary Flood, Anthony Gunter, Stephen Gall, Ray Vandenberg, Jeff Leisk and Craig Dack.

Gunter and Gall not only built legends for themselves; they were central in re-shaping a sport. Mates they might have been, but it was their conflict that ushered in a new era, and probably did more to enhance the sport and bring it within the reach of the general public than any other riders, before or since.

Related Content

YELLOW BELL MOTO-3: REVIVED!

Be the first to comment...