KTM’s 2018 TPI 2TS: Behind Its Design

Bernhard “Barny” Plazotta has been with KTM for more than 25 years, and for the past decade he’s overseen the R&D program for the brand’s off-road models at its Austrian HQ. In other words, Plazotta knows these machines – past, present and future – as well as anyone. At the recent launch for KTM’s all-new 2018-model 250 and 300EXC TPI machines in Austria, Transmoto’s Andy Wigan caught up with the straight-talking Plazotta and asked him to shed some light on the challenges of introducing fuel injection to these two-stroke machines, and to divulge what’s in the pipeline for KTM’s off-road line-up. Here’s the transcript of that revealing conversation.

TM: Help put the significance of these 2018 two-strokes in context for us, Barny.

BP: Well, I have been with KTM since 1992, and these fuel-injected two-strokes engines for 2018 have undoubtedly been one of the most important projects for KTM’s design team in the 25 years since I joined the company. Our 250/300cc two-stroke engine platform has been more or less the same since 1992. Of course, there were some big steps along the way – such as the switch to the hydraulic clutch and addition of the electric-start – but the really big steps for these two-stroke engines have come in 2017 and 2018. In 2017, in addition to being a completely new engine, the 250 and 300EXC was also fitted with a counter-balancer for the first time. And for 2018, we introduced the Transfer Port Injection, or TPI, fuel injection system for the first time. And this is a system KTM has patented.

So was the new-generation engine introduced for 2017 always destined to use fuel injection, and designed with that firmly in mind?

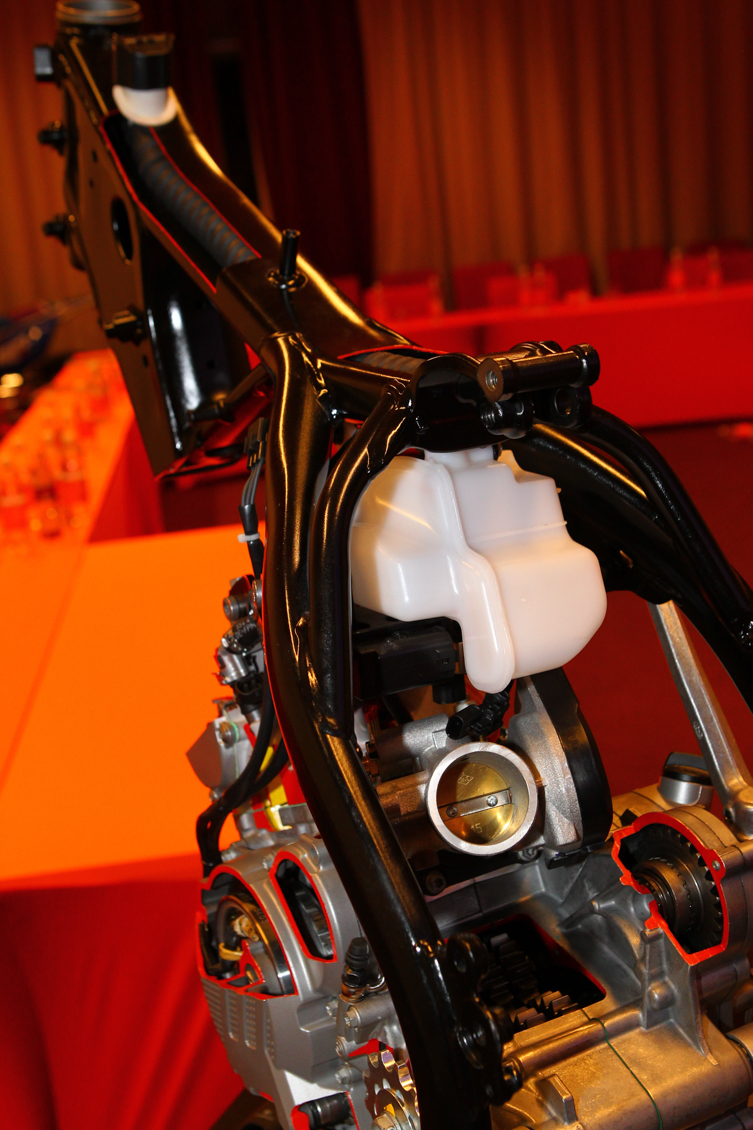

Absolutely. For us, the new counter-balancer engine was always designed with fuel injection in mind. But you have to remember that we had also been testing orbital and direct-injection systems before we developed the TPI. The orbital system required a high-pressure pump, which meant those engines’ crankcases had to be totally different. Then when we switched to the DI (Direct Injection) system, we could use basically the same cases as we did for the carburetted bikes, but they needed to be modified to accommodate the different oil lubrication system. Then finally, with the TPI system, we were able to use exactly the same engine cases that the carb bikes used; the only difference was with the cylinder, which was designed to incorporate the injectors.

A year ago, you admitted you’d initially doubted a 63 horsepower 500EXC could be rideable off-road. And this year, you conceded you’d been similarly sceptical about the injection system for the two-strokes. Is scepticism a healthy element in a design team?

Yes, I think scepticism is a very important part of the development process. It pushes you to ask questions you might not like the answer to. And it motivates you look for alternative ways, for better ways, to do things. With the large-capacity 2017-model four-strokes, that scepticism about being able to use so much horsepower inspired us to find creative ways to harness it into more user-friendly power delivery. And we achieved that. So, yes, I was sceptical about the first two injection systems we tested for several reasons…

The orbital system: The engine that used the orbital injection system looked good on paper and was very good at lowering emissions and overcoming any problems we had with the carburettor, but this design was focused almost entirely around emissions and homologation, and not on rideability. Plus, as I mentioned earlier, the orbital system’s high-pressure pump meant completely different engine cases were needed. We soon realised that the main target should be a bike that is rideable, and one that’s easy and cost-effective to maintain. Those targets could not be met with the orbital system.

The DI system: Some 18 months ago, we were actually very close to starting production with the DI bikes, but the final prototypes we tested revealed problems we hadn’t foreseen. The DI system worked pretty well on the 250, but we had difficulties to in keeping the piston cool on the 300, which meant reliability suffered. The reliability of the injectors was also questionable. In the end, we decided there were too many problems with the DI system that we could not properly solve.

The TPI system: A lot of people said that, in principle, we would never be able to develop a fuel-injection system for two-strokes that would perform consistently well in all conditions. For example, when you ride through a large puddle or creek that suddenly makes the exhaust pipe much cooler – a situation that a carburettor bike is ‘naïve’ to – then you need to find a way to override the information that the TPI bike’s EMS is receiving to ensure it continues to run properly. That is just one example of the complexity and challenges that came with developing the TPI system’s mapping. But the TPI system was by far the best solution when it came to meeting our deign objectives – which were primarily to keep the power characteristics, feel and exhaust note of the TPI models as close as possible to the carburetted engines.

You’ve said the orbital and direct injection systems failed to match the carburetted bikes’ performance – in terms of power, feel and sound. Were ‘feel’ and ‘exhaust note’ really major considerations?

Yes, they were. You ride a motorcycle because you have a passion for it. And two-stroke fans like the bikes’ noise and smell [laughs] and the way they deliver their power. The exhaust note produced by the orbital system was annoying; like something was wrong with the engine. If I were a consumer, this would be enough for me to decide against buying the bike. With the DI engine, it was easier for our test riders to identify where in the rev range it was too rich or too lean, and that allowed us to optimise the mapping pretty quickly. But the DI engine still fell short of the carb bike for outright power and throttle response. In other words, its overall power character – or ‘feel’ – was not so good.

At previous launches, KTM’s design team has typically been two or three years ahead of the ‘new’ model they were releasing. But with these 2018 TPI bikes, it seems like there was very little lead-time. Was your design team rushed?

It’s fair to say we have been more relaxed with previous year-model releases. For these 2018 bikes, we had a really tight time schedule for the simple reason that we had to fulfil all the Euro4 regulations. If we failed to do that, we would lose around 14,000 units, which would have had a large financial impact across the company. So there was a lot of pressure from the company’s Board.

It was great to see you riding the bikes yourself at the launch this year, Barny. In your mind, what is the biggest difference between the carb-fed and TPI models?

One of our main objectives was to keep the rideability and power characteristics of the TPI models as close as possible to the carburetted engine, while eliminating the disadvantages of the carb engines – such as the need for re-jet for different elevations, humidity, etcetera. And we have achieved this. The standout thing for me is that the TPI engines are easier to ride everywhere. The TPI power is more tractable and lets you crawl up a hill at very low revs, and yet the engine never feels like it wants to stall. It’s more responsive than the carb bikes, especially at lower revs, but it’s not aggressive. Plus there is never any need to rev the engine to ‘clear it out’ on long downhills, and both the emissions and fuel consumption is reduced by a large amount.

Which capacity is your favourite, and why?

The 250 has always been my favourite two-stroke, and it still is for 2018. Our focus was to get some more torque from the 2018 250EXC because that was the most frequent request from our customers, particularly from guys who ride our two-strokes in extreme and technical terrain and wanted to be able to use less clutch. In other words, we wanted to make the bike easy to ride in difficult conditions.

Why have KTM’s factory racers been hesitant to embrace the TPI bikes?

We have got the mapping quite good for the production bikes. But top race guys often ask for something different to suit their riding style or power preference, or other engine mods they’ve made to their bike. For example, riders such as Christophe Nambotin and many of our motocross guys like to run their bikes very rich. With a carb bike, this is easy as it requires only a small change to a jet or a needle. So for the TPI models, our next step is being able to develop, and make available, maps that satisfy those different set-up tastes to suit a certain riding style or preference.

How significant is the change to the fork’s upper stanchion, which was accompanied by firmer damping in these 2018 bikes?

It’s a small change that has produced a significant improvement. With the inner and outer fork tubes now bending in a more uniform way, the 2018 fork has less stiction. That makes it more sensitive to small bumps, for a more comfortable ride. In turn, this allowed us to beef up the fork’s compression damping for more bottoming resistance. The new Xplor fork was very well received when we introduced it to our EXC range a year ago, and our feedback at the launch for the 2018 bikes suggests everyone noticed a clear improvement again this year.

To accommodate the new oil tank’s filler cap and pipe, holes have been cut into the frame. To what extent do they affect the frame’s flex?

They do not affect it at all. And of course, we did a lot of computer simulations to ensure we found the optimal position to put these holes. Where the filler cap hole is, the frame is very, very stiff. And the other hole – where the filler pipe exits the frame near the rear shock absorber mount – was already there on the models that run a linkage. This was designed to give the frame more flex in that area. We simply took advantage of that existing hole to route the lower end of the filler pipe to the oil tank.

And did that dictate where the oil tank would be positioned?

Well, that space in front of the upper shock mount was already there because we are obliged to fit a canister to the bikes we made for the USA (for street-legal enduro bikes in the US, it is regulated that all the hoses related to emissions or evaporation are routed into a canister that sucks out those gases). This was very convenient because we had run out of space with our enduro models, and we did not want the addition of the new oil tank to compromise how slim the bike was. The oil tank’s position also means it’s very well protected and keeps the weight in the centre of the bike, plus the design meets our objective of making system user-friendly to fill for owners. And just to clarify, we have not moved the fuel tank backwards to accommodate the new filler cap. We have only taken 5mm off the front of the tank so it doesn’t get in the way when you’re undoing the filler cap, and the fuel tank’s filler cap has moved a corresponding 5mm backwards. Also, we have already made a larger-capacity fuel tank that fits both the four-strokes and these TPI two-strokes.

As you said earlier, these 2018 TPI two-strokes represent one of your design team’s most important projects. But what can we expect in terms of how this technology is evolved and applied in the years to come?

Our plan has always been to introduce this new system successfully on the 250 and 300cc enduro bikes, and then develop it for the smaller-capacity bikes – the 125 and 150cc models. Following that, we will look at adapting the technology to the cross-country and motocross models. Also, as we transition from carb to TPI models, there will come a point when it does not make commercial sense for companies to continue producing small numbers of carburettors. And in the USA, there is a push (under their ‘Red Sticker’ regulations for competition bikes) to get rid of carbs all together. So in the next three to four years, I think fuel injection is inevitable for these other two-stroke models. Now that the two-strokes have the all-new EMS (Engine Management System), some people have asked when traction control will be introduced to them. But we are not 100% certain that traction control will be of benefit to these bikes.

Thanks for your time, Barny.

My pleasure.

More on KTM’s TPI Two-Strokes

🎥 TESTED: 2018 KTM EXC TPI LAUNCH

Be the first to comment...