Heritage: Paradise (Tracks) Lost

They built ’em big back in the day – circuits, that is. Sure, land was cheaper, and there was lots more of it that had yet to be adulterated by houses and factories. Scrambles circuits in the ’50s and ’60s tended to conform to motorcycle cross-country racing – the origins of modern-day motocross, which were held on sprawling terrains and following the natural lay of the land. But as the decades tumbled, these iconic tracks became victims of changing social and economical times; the greatest rider battles on the circuits giving way to the bigger social battles off it. Gone, but not forgotten, their legacy remains as the birthplaces of the sport of off-road racing in an emerging Australia.

![]()

Circuit: The Ropeworks

![]()

Location: Mosman Park, Perth, WA

Lifespan: 1928 – 1964

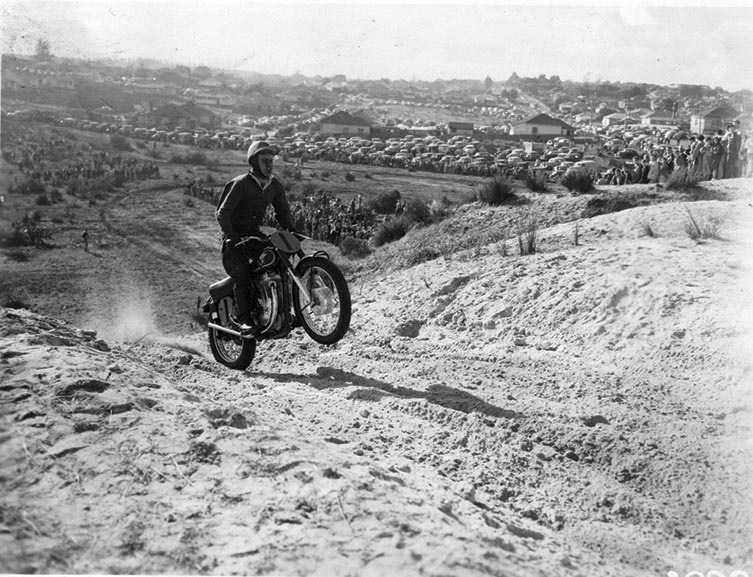

Arguments will rage in perpetuity as to exactly where and when the first organised scramble/motocross event in Australia took place, but it’s a safe bet to say that the first large-scale such meeting happened in Perth on June 17, 1928, at Mosman Park. Today, this chunk of coastal splendour is amongst the most exclusive and expensive real estate in Australia, but back then, it was a valley ringed with sandstone cliffs, with fat paddymelons strewn across the sandy tracts, and home to little more than a factory producing rope. Two pioneering WA riders, Aubrey Melrose and Roy Charman, had recently returned from Britain where they had competed in a variety of events the previous year.

These ranged from the Isle of Man TT to the International Six Days Trial, the rugged Scott Trial and numerous scrambles events. Both were members of the Harley Motorcycle Club of WA and, armed with their firsthand knowledge of the new sport of scrambling, proposed the club run an event at Mosman Park. A 4.8km circuit was laid out, appropriately christened ‘The Ropeworks’, and the first Harley Scramble took place in 1928. The circuit was incredibly punishing on the rudimentary machines of the day – a lap of the track included winding up and down steep cliffs (known as slides), back and forth across high-speed flats and through a quarry section. The ascents were so steep that gangs of helpers were stationed at the top, armed with ropes and grappling hooks to haul stricken riders to the top if they failed mid-climb.

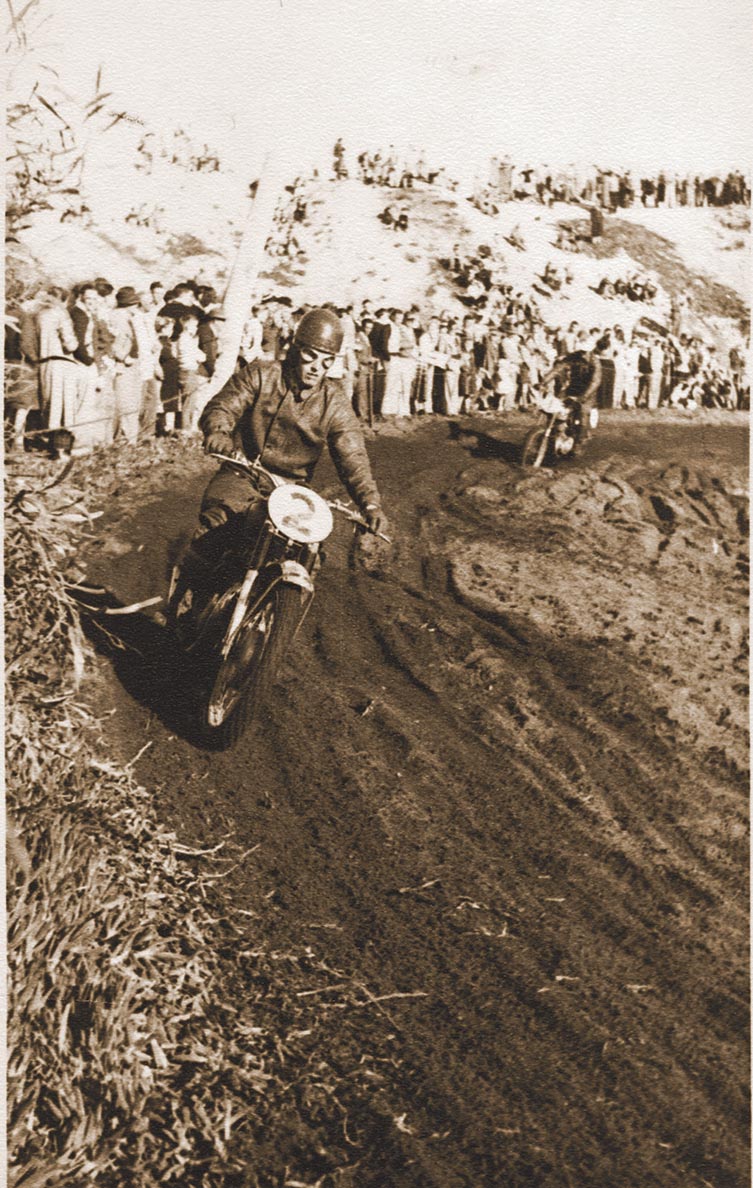

Peter Nicol, wearing the #1 plate while riding WA’s The Ropeworks circuit.

The race was over 100km, with 10 laps in the morning and 14 in the afternoon, and with each lap taking more than six minutes, it was an arduous affair. As on the Isle of Man, riders started in pairs, 10 seconds apart, with the fastest riders at the rear of the field. Notwithstanding ability, fitness and machine preparation were the deciding factors in success or failure. Some of the better-equipped riders placed spare wheels, chains and other parts at strategic points around the circuit to keep their machines going in order to simply record a finish; which usually only applied to a small percentage of the original field. That first race was won by Ken Vincent on a HarleyDavidson, and the following year Melrose himself – a gifted competitor who would go on to a successful car racing career – won, also on a Harley. Throughout the ’30s, the star rider was Les Clinton, first on Harleys and later on British machines. The scene changed dramatically after the war, as special competition bikes became available, but the Ropeworks course remained as rugged and punishing as ever, maintaining its status as the premier off-road event in Australia. Crowds of 15,000 were not uncommon. Continuing his pre-war dominance, Clinton won again in 1946 and 1948, and notched up a total of 17 starts, the last being in 1960.

Ropeworks’ Star: Peter Nicol

As a 17-year-old, Peter Nicol had his first tilt at the Harley Scramble in 1948, riding a rare 350cc Royal Enfield Competition model. It took him just three years to lift the crown when he defeated a field of 89 riders to win in 1951 – the first of a record five victories, the final one coming in 1957. It could have been five in a row, had he not collapsed a rear wheel while leading in 1956. As well as being WA’s top scrambles rider, Nicol was equally at home on the tar, riding a KTT Velocette and a Manx Norton. He was actually nominated for Australia’s Isle of Man team in 1954 but declined, to concentrate on his business. Because of the vast distances involved, interstate trips were infrequent, but when Nicol ventured to Sydney for the Australian Championships in 1956, he beat a classy field to win the 350cc title.

Glory Days

Entries continued to swell and by 1954, 107 riders faced the starter, although just 21 made it to the finish. The afternoon section was extended to 16 laps, and just to add a further degree of difficulty, it rained for most of the day. Peter Nicol, on a 500 Matchless, went on to take his third victory, from Bill Watson and Ron Edwards. When the official Australian Scrambles Championship was instigated in 1954, it was only natural that the Ropeworks course should get a chance to host the prestigious event, and this happened in 1955. As well as the top locals, the State Champions from Victoria (Les Sheehan), South Australia (Jim Silvey) and NSW (Charlie Scaysbrook) were nominated. Sheehan had just returned from England with an ex-works 500 AJS after riding as a member of the AJS team in Britain and Europe, but faced a formidable line up including Nicol, three-times winner George Scott, Edwards and Watson on BSA Gold Stars, and the evergreen Clinton, who had forsaken his Harley for a 500 Matchless. 112 riders came to the line for the all-in event that contained individual classes for 250, 350 and Unlimited Championships.

After the opening 10 lap leg and one hour of flat-out racing, Sheehan came home first outright and in the Unlimited class, with Nicol second and leading 350 ahead of Scaysbrook on his rigid-framed Matchless. But the afternoon session brought only despair for Sheehan, who retired with a broken frame, leaving Nicol to win again from Edwards and Watson. Over 15,000 people went home knowing they had seen the best day’s scrambling yet. Over the next five years, the Harley Scramble continued its annual course, not completely oblivious to the rapidly encroaching civilization on the edges of the circuit. 1960 saw the last Harley Scramble run on the original two-heat format and over the full-length course, and was won by Doug Cutts from the south-west town of Manjimup, riding a 650 Triumph. But by 1964 the residents had their victory, and the 32nd running of the Harley Scramble become the final one at the Ropeworks. Thereafter the event continued in name at the country town of York, 100km east of Perth, but to all and sundry, it was a pale imitation of that supreme test of stamina and ability that had begun 36 years before.

McMansions have claimed the mud that once made up Perth’s Ropeworks circuit.

![]()

Circuit: Moorebank

![]()

Location: Moorebank, Liverpool, NSW

Lifespan: 1954 – 1970

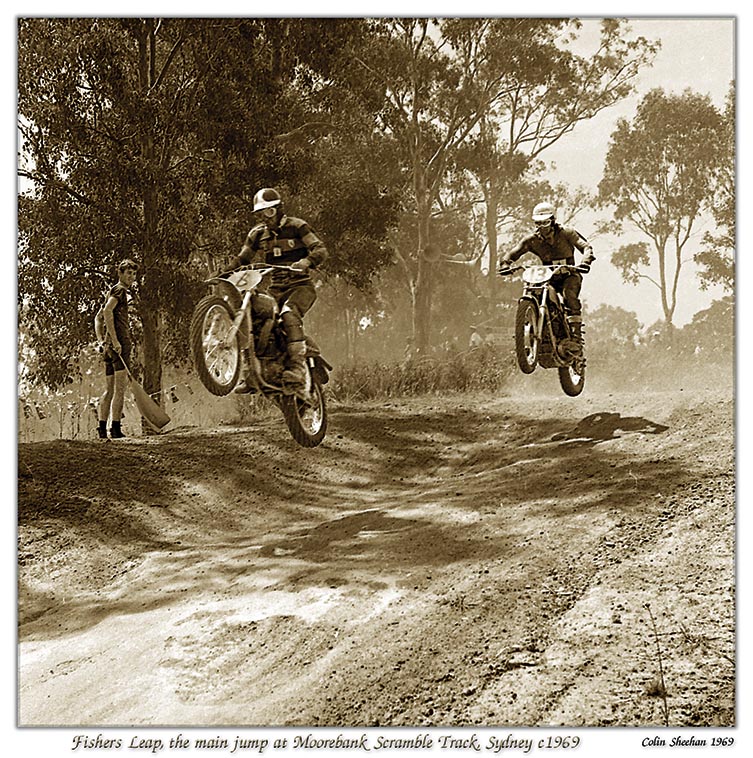

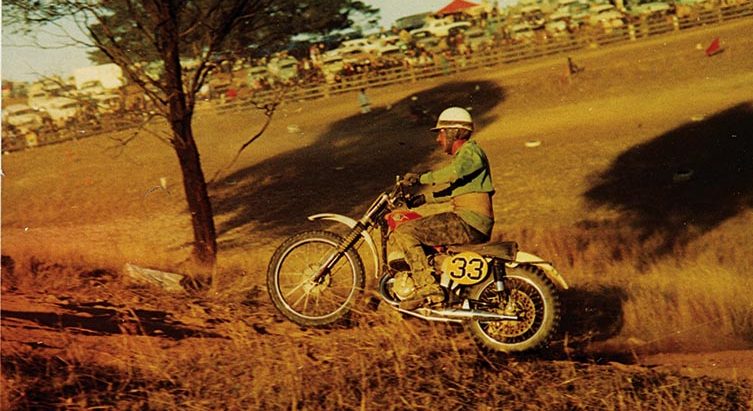

NSW had a different motorcycling culture to WA, in that the focus was on road racing, which, with the exception of Mount Panorama, was usually on dirt surfaces and known as Miniature TT. But a scrambles scene did exist, on tracks like Glenfield, near Liverpool, and Holdsworthy. However, it was the building of the circuit in the army grounds at Moorebank, on the shores of the Georges River, that really kicked the sport into the bigtime. The area was full of dense scrub and the lower reaches were a maze of swamps, fed by the overflow from the Casula Sewer Treatment Works, which overlooked the site. A rudimentary circuit had been there for some time, used by army Dispatch Riders and even tanks for training purposes. Members of the R.A.E.M.E. Army Motorcycle Club, plus helpers from several other clubs, toiled long and hard to extend this track and to clear the site, and fence off spectator areas. The first meeting took place in May, 1954, in front of a crowd of 5000. The venue was an instant success, and the track was gradually extended to over 2km. Moorebank had several distinctive features – The Leap, later known as Fisher’s Leap, was a natural round-top hill with a long downhill landing ramp that launched bikes high into air and drew huge crowds that lined the fence. Sorbent Hill was a man-made obstacle that finished in a nearly sheer drop – an anal-clenching experience that gained its name from the well-known toiletry product. But the bit that separated the men from the boys was simply known as the Sand Section – a 300m stretch of white sand with a line of scrub separating it from the Georges River. This churned up into giant waves and many of the barely-converted road bikes of the time found the going nearly impossible. The fast blokes took it flat out, skimming across the surfaces of the whoops.

The Bigtime

As testimony to Moorebank’s growing stature, the Australian Scrambles Championship was awarded to the Sydney circuit for May, 1956. In the months preceding the big event, much work was put in to improve facilities – adding a canteen, toilet bocks and a commentator’s tower – all of which survived to the very end. A mammoth crowd poured in to see the glamour entry, which included five West Australians, five South Australians and a large Victorian contingent. On the day, the interstaters gave the locals a riding lesson, with second in the 250 class (Blair Harley) and third in the 500 class (Charlie Scaysbrook) the only placings by NSW riders. Victorian George Bailey took the 125, 250 and 500 sashes back home, while Peter Nicol retained his 350 crown. To really rub it in, the Unlimited Championship saw a clean sweep by WA riders, with young BSA-mounted Charlie West winning from Nicol and Don Russell. It was a grand meeting, and one that was talked about for many years. In 1961, Moorebank was again awarded the running of the Australian Championships. Charlie West, now with European experience behind him, brought his immaculate fleet of three BSAs, and was accompanied by reigning 250 Champion, Gordon Renfree, and Glen Britza, who fronted on one of the first of the new-fangled English scramblers – a Greeves Hawkstone. While the lanky Britza’s fiery style brought him undone on the day, the speed of this ungainly looking machine made a lasting impression on everyone. The third and final leg of the Senior Championship was probably the single most famous race ever staged at Moorebank. Fisher and West went into the round locked on points, having won a leg each. For most of the race, Fisher, mounted on a Triumph/ BSA hybrid, tried everything he knew to outrace West’s 500 BSA Gold Star. Spectators ran in droves from one viewing spot to the next, following the spectacular battle as it raged around the circuit. First Fisher led, then West, until Fisher misjudged a corner and found himself motor-deep in the putrid swamp. Still not defeated, he struggled free and began a seemingly impossible chase, regaining the lead on the next-to-last lap. Never was there a more popular victory at Moorebank, but West had the consolation of taking both 250 and 350 titles. NSW took another title when veteran Ray Dole on his Victa lawnmower-powered BSA Bantam won the Ultra Lightweight. Charlie West became a regular competitor at Moorebank, driving between Perth and Sydney and often combining scrambling at Moorebank and speedway midget car racing at Claremont in the same week.

International Flavour

An ambitious move by a combined group of promoters saw Moorebank stage its first, and only, international meeting in 1968. Randy Owen and Gordon Adsett represented England, with an unknown Austrian, Alfred Postman, and New Zealand stars Alan Collison, Ross McLaren and Brian Franklin. Not surprisingly, Owen and Adsett ravaged the field on their 360 CZ and Husqvarna machines, leaving Australia’s best looking very secondhand indeed. By now Moorebank was beset with problems. With the onset of the Vietnam War the military found the excuse it needed to resume using the land. Seventeen years before, the riverbank on the Liverpool side was unblemished bushland; by 1970, it was a mini-city and expanding at an unstoppable rate. Everyone knew that the end was near. So when, on November 15, 1970, the final curtain swept down, it came as no great surprise, and Moorebank passed on with scarcely a tear shed.

Moorebanks Star: Matt Daley

Queenslander Matt Daley moved to Wollongong in 1966 when he was offered a ride on the 250 Cotton, formerly raced by Graham Bartholomew. From the moment he threw a leg over the saddle, the superfit and determined Daley was dynamite, particularly at Moorebank. When he later acquired a new 250 Husqvarna, he properly found his stride. Occasionally, Matt’s colours would be lowered by someone like Laurie Alderton or Gary Flood, but not very often. In 1968, he switched to CZ, with a 250 and 360 at his disposal and the following year, was back on Husqvarna with a new 360. With several Australian titles and literally dozens of Moorebank victories under his belt, Daley headed for Europe, where he spent a successful season on the same Husqvarna before shifting to USA, where he became the man to beat in the state of Florida, riding for the Yamaha distributor.

Factories, rather than family homes, bury the mud and memories of the Moorebank circuit

![]()

Circuit: Christmas Hills

![]()

Location: Melbourne, Vic

Lifespan: 1964 – 1975

Nestling 35km north-east of Melbourne in the Dandenong Ranges, Christmas Hills is now dominated by the Sugarloaf Reservoir, which was opened in 1981. Buried under 96,000 megalitres of water deep in the 440ha reservoir, is one of the best scrambles tracks Australia has ever seen. The Christmas Hills circuit was yet another project of the incredibly energetic Hartwell Club in Melbourne – a club that boasted many of the top riders in scrambling in the early-’60s; John and Mike Burrows, Bob Walpole and Leon Street just a few of the big names. It was ‘Big John’ Burrows, who began negotiations with a local landowner, Stan Ashmore, to construct a track on land at Christmas Hills. In May, 1964, the track opened by promoting Victoria’s most prestigious such event – the Ron Hunter Memorial Grand National, named after the club’s former president who was tragically killed at a grasstrack meeting. The circuit ran on both sides of a steep gully, with black loamy soil that soaked up water like a sponge. With a lap of almost 2km, it was extremely physically demanding – especially in wet weather – and was also very fast with a long downhill main straight. That first Grand National win went to Ian Gaff. The event was also notable for the final capitulation by the Auto Cycle Union of Victoria to allow riders to wear football jumpers instead of the previously compulsory leather jackets.

Christmas Present

By the mid-’60s, scrambles was booming in Victoria, and Christmas Hills was the showpiece of the action. Naturally, the track got the nod when it was Victoria’s turn to host the Australian Scrambles Championship in October, 1966. It was a truly massive event, with capacity fields in every class and a monster crowd to see riders from every state do battle. It was also a day when Victorian riders stamped their almost complete dominance on the titles, with only South Australian Graham Burford on a 250 CZ managing to steal a championship from the host state. In fact, Burford was denied a chance to challenge for the 500cc title because his 360cc CZ was under the 400cc minimum for the class, which went to Ray Fisher and his Matchless Metisse. The main event, the Unlimited Championship over 15 gruelling laps, went to John Mapperson’s 250 Bultaco, after his rivals dropped out one by one. In 1967, Christmas Hills hosted the Victorian leg of the International Series, organised by ex-pat Aussie Tim Gibbes. The imports comprised Welshman John Lewis, Swedish Husqvarna works rider Gunnar Lindstrom, American desert racer J.N. Roberts and Kiwis Ivan Miller, Morley Shirriff and Gordon Holland. Lewis and Lindstrom did most of the winning, although local Greg Leaney put in some outstanding rides, while the spectacular Shirriff came under fire from the staid ACU officials for dangerous riding – wheelstanding his Triumph Metisse the length of the main straight!

Flood Warning

The circuit’s main event each year continued to be the Grand National, which was increased in length from 20 to 25 laps in 1970 and won by John Mapperson on a 400 Husqvarna. About this time, plans for the Sugarloaf Reservoir were announced by the Victorian Board of Works, but racing continued for another five years before the club was finally forced to vacate the site and relocate their motocross activities to Seymour – a featureless venue that had nothing like the character or visual splendour of Christmas Hills.

Now that’s a waterlogged track! Christmas Hills became the Atlantis of circuits.

Christmas Hills’ Star: Ray Fisher

In the words of several of his contemporaries, Ray Fisher was “nothing special” in the years before he packed his bags and headed to Britain in 1960. This may be a little harsh – Fisher had enjoyed reasonable success, including the Victorian Unlimited title in 1958 on his BSA Gold Star – but the five years he spent away transformed him into star-quality. Riding almost year-round in Europe and in the punishing British winter scrambles, which sometime included snow and sleet, Fisher returned in 1965, bringing with him the first Rickman Metisse seen in the country, this one fitted with a 500cc Matchless engine. Fisher’s effortless style belied his sheer speed and he swept to a string of successes that included around a dozen national championships. At Christmas Hills, he was sheer poetry to watch, as the circuit resembled some of the big European-style tracks where the Matchless could stretch its legs. But he also saw the writing on the wall for big four-strokes, and successfully made the switch to the new breed of two-strokes, first on CZs, then on Montesas, and also scored Kawasaki’s first national championship when he won the Australian 125 title at Collie, WA, in 1969.

More Iconic Aussie Heritage

THE ORIGINAL MOTO RIVALRY: GALL VS GUNTER

Brilliant read and awesome History thanks so much Jim and Andy for sharing it. Simply Gold!