KTM’s Two-Stroke EFI: How it Evolved

Between the early 1990s and 2017, KTM’s 250/300cc two-stroke engine platform didn’t change much. Sure, there were refinements and some landmark changes – such as the switch to the hydraulic clutch in 1997, the addition of the electric-start in 2008, the all-new two-stroke engine in 2017, which was fitted with a counter-balancer for the first time. But the introduction the Transfer Port Injection (or “TPI”) fuel injection system to the 2018 250EXC and 300EXC is arguably the most significant change ever made to KTM’s two-strokes models.

What many people don’t realise is that the evolution of KTM’s fuel-injection R&D program kicked off in 2004 in collaboration with Australian company, Orbital; that a ‘Direction Injection’ system almost went into production a few years ago; and that the breakthrough ‘Transfer Port Injection’ system was discovered almost by accident as recently as 2014. And from that point onwards, the development of the complex TPI technology has consumed huge amounts of KTM’s R&D department’s time and resources.

So let’s reflect on the origins of KTM’s aspirations to build a fuel-injected two-stroke engine, and trace the steps the Austrian manufacturer took en route to the introduction of the world’s first fuel-injection production off-road competition motorcycle just 12 months ago; technology that allowed KTM to meet the stringent new Euro4 regulations and yet still retain their “Ready to Race” performance ethos.

THE ORBITAL SYSTEM

What is it?: It’s an air-assisted fuel injection system. The air and fuel was mixed in a pre-chamber and then, under high pressure, injected into the combustion chamber directly. The project kicked off in 2004, developed by KTM in conjunction with an Australian company called Orbital, and the first running prototype came in 2006.

The Challenges: The engine that used the orbital injection system looked good on paper and was very good at lowering emissions and overcoming any problems with the carburettor, but the design was focused almost entirely around emissions and homologation, and not rideability. Fuel consumption and performance was average, and the orbital system’s high-pressure pump meant completely different engine cases were needed. Plus the pump and associated plumbing made the engine a nightmare to fit into the existing frame without major modifications – something the chassis designers didn’t want a bar of. KTM’s design team soon realised that the main target ought to be a bike that is rideable, and easy and cost-effective to maintain. And they conceded that those targets could not be met with the Orbital system.

THE DIRECT-INJECTION SYSTEM

What is it?: This next-generation engine came in 2012, with two injectors positioned laterally and injecting directly into the combustion chamber. It was simple and lightweight and robust. And compared with the Orbital system, it used a lower pressure (3.5 Bar) direct-injection system, developed by KTM in collaboration with a technical university in Graz, Austria.

The Challenges: It had much better rideability than the engine with the Orbital system. In late 2015, KTM was actually very close to starting production with the DI bikes, but the final prototype testing revealed problems they hadn’t foreseen. The DI system worked pretty well on the 250, but there were difficulties in keeping the piston cool on the 300, which meant reliability suffered. The reliability of the injectors was also questionable. In the end, KTM decided there were too many problems with the DI system that they could not properly solve.

THE TRANSFER PORT INJECTION SYSTEM

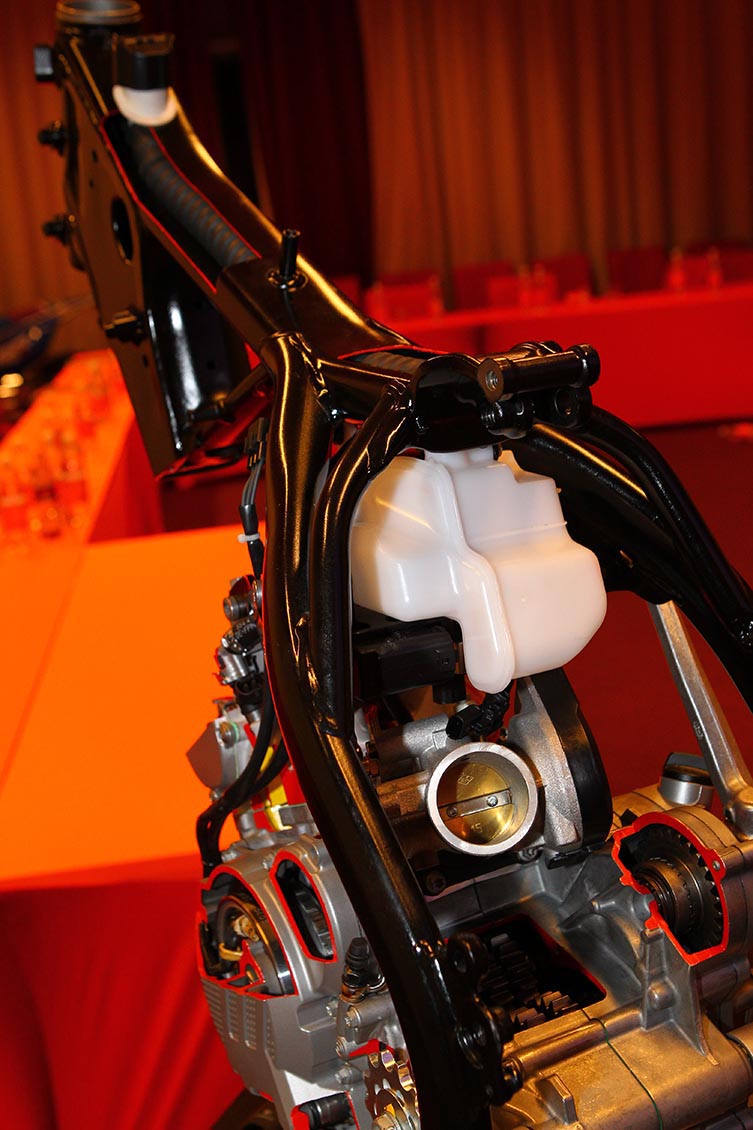

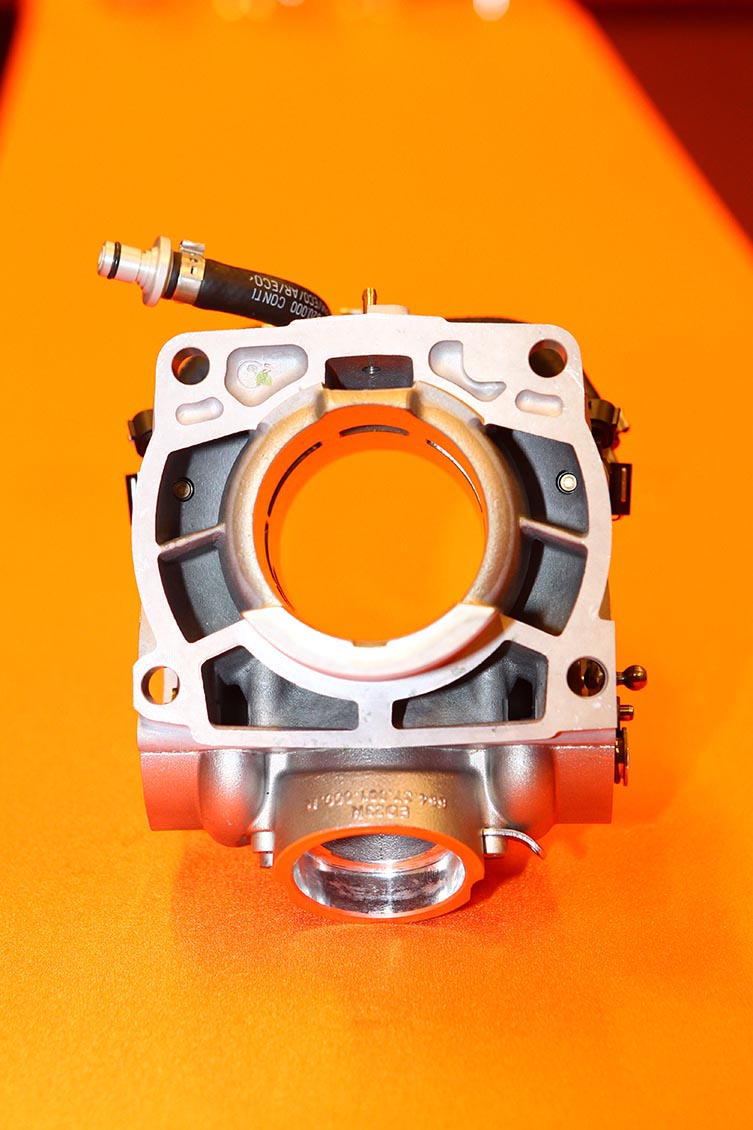

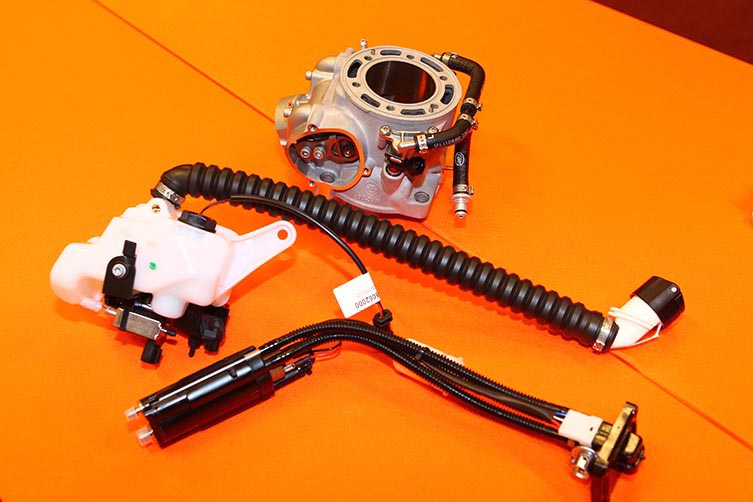

What is it?: With the TPI system, fuel is injected into the barrel’s transfer ports via two injectors. By injecting the fuel against the airflow direction in those ports (rather than injecting directly into the combustion chamber), KTM found it created a much better mixing of fuel and air, and a more efficient combustion. The oil still finds its way into the engine’s crankcases, but via a 39mm throttle body, not a carb. The oil is fed at low pressure from a 700ml tank that’s mounted under the seat, and atomised by the reed block. By separating the way fuel and oil are ingested by the engine, there no longer needed to be a compromise in the fuel-to-oil ratio to ensure engine parts are adequately lubricated. Instead of the 50 or 60:1 ratio recommended for KTM’s carb-fed two-strokes, the 2018 bikes run at anywhere between 70 and 150:1, depending on a number of engine parameters (RPM, throttle position, load, etc).

The Challenges: Initially, the TPI engines experienced flameouts because the exhaust pressure wave demanded a more sophisticated EMS that could perfectly manage fuel metering. When these refinements to the EMS were finally sorted, KTM knew they were onto a winner. And they promptly slapped an international patent on the TPI technology. A lot of sceptics said that, in principle, KTM would never be able to develop a fuel-injection system for two-strokes that would perform consistently well in all conditions. For example, when you ride through a creek that suddenly makes the exhaust pipe much cooler – a situation that a carburettor bike is ‘naïve’ to – then you need to find a way to override the information that the TPI bike’s EMS is receiving to ensure it continues to run properly. That’s just one example of the complexity and challenges that came with developing the TPI system’s mapping. But the TPI system was by far the best solution when it came to meeting KTM’s primary design objectives – which were to keep the power characteristics, feel and exhaust note of the TPI models as close as possible to the carburetted engines.

For a more detailed insight into the challenges that KTM’s engine design team encountered while developing their two-stroke EFI systems over the past 14 years, check out this fascinating interview with KTM’s engine guru, Michael Viertlmayr.

KTM DESIGN TEAM INSIGHTS…

According to Barny Plazotta, who has worked at KTM for more than 25 years and overseen the off-road models’ R&D program for the past 12, “These TPI fuel-injected two-strokes engines for 2018 have undoubtedly been one of the most important projects for KTM’s design team in the 25 years since I joined the company. Sure, the introduction of the completely new 250/300EXC engine in 2017 – fitted with a counter-balancer for the first time – was a landmark for us. But you have to remember that the counter-balancer engine was always designed with fuel injection in mind. Also, we had been testing Orbital and Direct-Injection systems before we developed the TPI engine. The Orbital system required a high-pressure pump, which meant those engines’ crankcases had to be totally different. Then when we switched to the DI system, we could use basically the same cases as we did for the carburetted bikes, but they needed to be modified to accommodate the different oil lubrication system. Then finally with the TPI system, we were able to use exactly the same engine cases that the carb bikes used; the only difference was with the cylinder, which was modified slightly to incorporate the two injectors,” Platzotta went on to explain.

KTM’s R&D team also pointed out that the Orbital and DI systems failed to match the carburetted bikes’ performance in terms of power, feel and sound, stressing the fact that ‘feel’ and ‘exhaust note’ really were major considerations for them. “You ride a motorcycle because you have a passion for it, Plazotta says. “And two-stroke fans like the bikes’ noise and smell [laughs] and the way they deliver their power. The exhaust note produced by the Orbital system was annoying; like something was wrong with the engine. If I were a consumer, this would be enough for me to decide against buying the bike. With the DI engine, it was easier for our test riders to identify where in the rev range it was too rich or too lean, and that allowed us to optimise the mapping pretty quickly. But the DI engine still fell short of the carb bike for outright power and throttle response. In other words, its overall power character – or ‘feel’ – was not so good.”

Those challenges with the DI system meant that KTM was really up against it when it came to meeting the Euro4 regulations (that would first apply to their 2018 models, released mid 2017), and yet not compromise performance and the brand’s ‘Ready to Race’ mantra. “For the 2018 TPI bikes, we had a really tight time schedule for the simple reason that we had to fulfil all the Euro4 regulations,” concedes Plazotta. “Thankfully, the TPI system allowed us to achieve our main objective of keeping the rideability and power characteristics of the TPI models as close as possible to the carburetted engine, while eliminating the disadvantages of the carb engines – such as the need to re-jet for different elevations, humidity, etcetera. The standout thing for me is that the TPI engines are easier to ride everywhere. The TPI power is more tractable and lets you crawl up a hill at very low revs, and yet the engine never feels like it wants to stall. It’s more responsive than the carb bikes, especially at lower revs, but it’s not too aggressive. Plus there is never any need to rev the engine to ‘clear it out’ on long downhills, and both the emissions and fuel consumption is reduced by a large amount,” Platzotta went on to say.

MORE ON KTM’S TPI TWO-STROKES

KTM TWO-STROKES: ENGINE DEVELOPMENT

KTM’S TPI 2TS: BEHIND ITS DESIGN

🎥 TESTED: 2018 KTM EXC TPI LAUNCH

Be the first to comment...