Australia’s Wil Ruprecht: World Enduro Champ (Pt 1)

For more than a decade now, Wil Ruprecht has been a gun off-road racer. He won Junior titles in the Australian Off-Road Championship (AORC) in 2013 and 2014, the EJ title in 2016, and the E1-class title the following year. But then, just as his lifelong dreams to race the Enduro World Championship began to materialise, he was struck down with a debilitating virus.

So, how did Wil Ruprecht work his way out of the physical abyss? What was the secret behind his uncanny ability to adapt to racing in Europe? Who was his inspiration to become world champ? How does it feel to be just the fourth Aussie to ever win an Enduro World Championship? What was the real story behind his last-minute withdrawal from the Aussie ISDE team? And is it true that he’s already jumped ship and signed on to race with the CH Racing Sherco team for 2023? We caught up with the down-to-earth, Taree-born 24-year-old to answer those questions and more…

TM: Hey, Wil. It’s been a while. How’s things, champ? Literally, CHAMP!

WR: I’m good thanks, Andy. Kind of weird that the racing season is now over, but I’m busier than ever. I already miss the routine that racing a championship brings with it. Life’s harder now that I’m not training [laughs]. I’m tidying up some loose ends over here in Italy – changing teams and getting a new apartment sorted for next year. I’ve had a bunch of commitments with sponsors, and I’m heading to the EICMA motorcycle show this weekend. And then, finally, I’m coming home to Oz for December and January.

“It feels like 20 years since I won those AORC titles in Australia. It feels very special to finally realise a childhood dream.”

Yes, word on the street is that you’re on a new team in 2023, and we’ll get to that shortly. Meantime, now that the world title win has sunk in, how’s it feel? You’ve come a long way from winning the AORC’s EJ and E1 class titles in 2016 and 2017!

Well, a lot has happened since then. Life goes pretty quickly when you get out of school and have to get a job to support your racing career; when you’re squeezing in your training after work, and when it’s touch and go whether getting a professional ride with a race team is going to happen for you. So, it feels like 20 years since I won those AORC titles in Australia! It feels very special to finally realise a childhood dream.

I hear your folks flew over to witness you clinching the Enduro World Championship title in Germany?

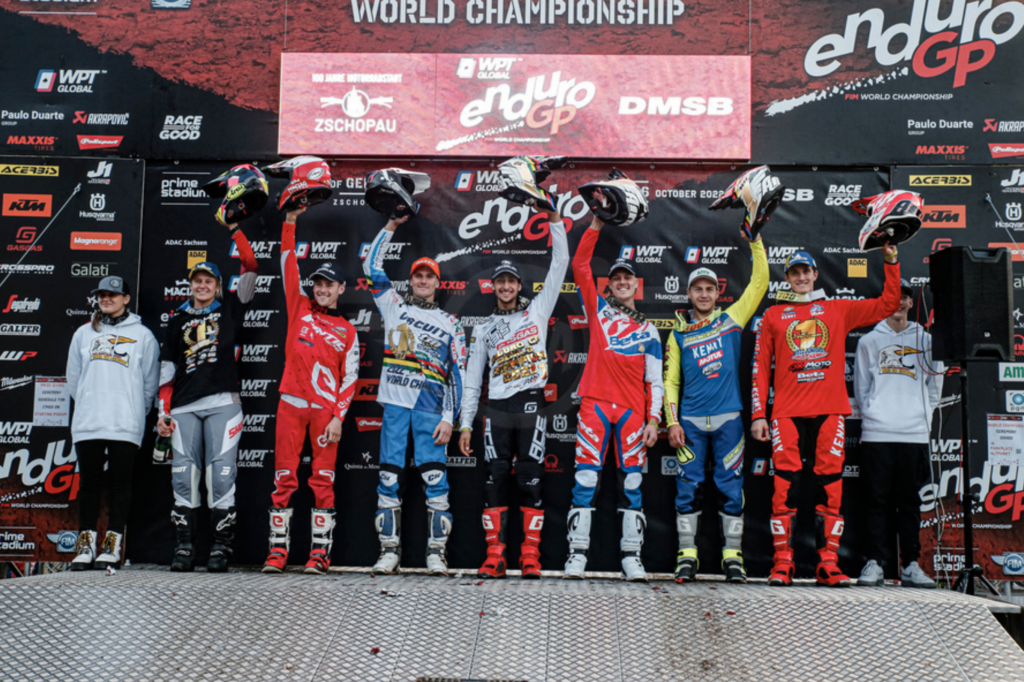

They did. My parents have been incredibly supportive. Looking back, there were a few times when I wasn’t sure about my racing career, and yet they hung in there and kept supporting my dream. And for that, I’ll be forever grateful. Because of Covid, my parents hadn’t been able to come over to Europe for a couple of years and they’d actually never been to a GP until this year. They came over to a few rounds this season and then flew in for the final round in Germany when I wrapped up the championship. They’ve been part of the process for 90 percent of the journey, so it was nice to be able to enjoy the moment with them.

What about others who’ve supported your racing? Were you swamped with well-wishers?

I was. Which is an incredible feeling. I’ve always made a point of keeping in touch with people who have supported me most throughout my career – especially guys like Trent Lean, who had a big influence on me and made it financially viable to race while I was a Junior. I can’t wait to get back to Australia to catch up with Trent and others who’ve supported me; to share a few beers around a campfire and tell them some stories about the past few seasons in Europe.

“I trained like a mongrel and had the attitude that, when I got back to Europe, I was going to win at all costs. And it worked.”

Let’s revisit the journey of how you got to Europe. Back in 2018, a couple of pre-season crashes sidelined you with shoulder injuries here in the AORC. Then, all of a sudden, you had a full-time ride with Johansson Yamaha in Europe. Tell us about how that opportunity arose.

Well, racing the Enduro World Championship was always by long-term goal for me. In that 2018 season, when I started riding the 450 in Oz with the Active8 Yamaha team, I had good pace, but, like you said, those shoulder injuries sidelined me for pretty much half the season. I was really fortunate that my team boss, AJ Roberts, helped create an opportunity for me to get a wildcard entry with the Johansson Yamaha team for the final round of the World Enduro Championship in Germany that year. I won the EJ class [Enduro Junior, Under 23] on the Saturday and that’s what attracted the attention of a few of the team managers. After that ride, I did a deal with Johansson Yamaha to race the full 2019 World Championship season in the EJ class.

Did being able to win on debut surprise you back then?

I knew I had the raw speed to win, but I really didn’t think it’d come that easily at my first race as a wildcard. Based on that experience, I started thinking to myself that, for 2019, if I just keep doing what I’m doing, then I’d have boys in the EJ class covered.

But that’s not how it played out in 2019, right?

No, not at all [laughs]. At the first race in 2019, I got my arse kicked. I mean, I went 3-2 in the class, but the gap to the guys winning the class was surprisingly big. As the bonuses were only 200 Euros back then, I was flying back to Australia to work as a removalist so I could pay for the next round’s racing. I trained like a mongrel and had the attitude that, when I got back to Europe, I was going to win at all costs. And it worked. Late that season, I actually posted the fastest Outright time for quite a few tests.

“Because of Covid, my parents hadn’t been able to come over to Europe for a couple of years and they’d actually never been to a GP until this year.”

But that’s when your body told you it had other ideas!

You could say that. I’d been struggling with my energy levels after being diagnosed with Mononucleosis, which is one of the strains of the Epstein Barr virus family. But halfway through that weekend’s racing, I’d just hit the wall completely. It’s hard to describe. It’s kind of like you’re in a bit of a drunk state; a bit delusional and seeing double. Which is obviously pretty dangerous when you’re racing. I did see a bunch of doctors and they were saying the only way I would recover was by spending three months on the couch, eating healthily and drinking lots of water to flush my blood. Anyway, I tried to continue for a few races. I’d ride like I normally would for the first two-thirds of Saturday, and then suddenly my times would be 20 percent off the pace. And Sunday was a horror story! So, I made the decision with the team to pull out of the last few rounds of that 2019 season in the hope we’d get on top of the health issues for the following year.

“Racing the AORC in Australia develops us into really fast riders, but the World Enduro Championship requires so much diversity in riding skill because its Extreme, Enduro and Cross tests are all so different.”

You shifted your European base from Sweden to Italy around that time. Was that part of trying to address your health issues?

Not so much. The Swedish set-up was good. The Johansson team was based there and they operated the thing well. The bikes were good enough for me to get the job done. But I’d come to the conclusion that it was an environmental thing. Sweden wasn’t providing me with what I needed to improve the areas of my riding where I was weak. Even though I didn’t know what team I’d be riding with for 2020, I decided to move to Italy – which is where most of the World Enduro teams are based, along with a few in France and Spain. In fact, I soon came to realise how much the moto industry revolved around what happens in Italy and what’s manufactured in that country.

In your mind, what areas of your riding needed improvement?

Racing the AORC in Australia develops us into really fast riders, which is a great asset to have. But the World Enduro Championship requires so much diversity in riding skill because its Extreme, Enduro and Cross tests are all so different. So, Aussie riders will soon discover that they’re missing something when they rock up in Europe. And that’s the primary reason I moved to Italy; to improve my speed in the diverse terrain it has to offer.

So, you rock up in Italy without a deal, and with a large question mark over your health…

Yep. It was a weird situation. The teams weren’t sure whether I actually had something wrong with me or whether I’d lost my drive and was giving up. And I can see how I might have felt like a gamble for the teams, given what had happened in the back half of 2019. That’s why I was appreciative when I got a deal with the Boano team, a satellite Beta team back then. We had a big squad in the team – like eight guys who were all around the same age – which made training fun. Though I was being really careful not to over-train because I still wasn’t sure how my body would hold up. Anyway, things started coming good that year. I started winning the Outright at a few rounds of the Italian Enduro Championship, but I struggled on the two-stroke. It felt like I could be fast on it, but I struggled to adapt to the two-stroke and my timing was out. By the end of the season – which was more like a half-season because Covid was kicking off back then – I’d bridged the gap to Hamish Macdonald, who won the EJ title that year, but still wasn’t fully where I wanted to be.

Which is why you were more receptive to the TM offer to race their four-stroke for 2021, right?

Yes. But there were several factors in that decision. Andrea Verona had just won a couple of titles with TM in the E1 class, and Loic Larrieu had won the E2 title aboard TM a year prior. I had some other opportunities, but TM had some good racing heritage and their bikes were evidently good enough, so I decided to lock into a two-year contract with them.

In hindsight, was that a good decision?

Yes and no. It was a good choice for me at the time and it set me up to win the title this year. And in 2021, I actually led the standings in the E2 class for most of the year. Unfortunately, I had an engine stop in one of the sand races late in the year, and [Josep] Garcia finished that season really strongly and piped me for the E2 title.

But second in E2 and fourth in EnduroGP/Outright is still a bloody good result for your first season in the big league!

It could have been better without the mechanical, but it helped confirm that I was a legit contender for the 2022 season. I won the Italian Enduro Championship Outright that year too, which was a bonus.

Why did you choose TM’s 300cc four-stroke? They’ve got a 450, so aren’t you giving away capacity unnecessarily in the E2 class?

The 450 is too fast; it has too much power for a majority of the terrain we race for the World Championship. Aside from a few of the older guys – like Alex Salvini, who’s attached to the idea of a 450 – most riders are electing to race a mid-capacity 300 or 350cc bike in the E2 class now. To be honest, the Enduro World Championship these days doesn’t give you the opportunity to use a 450’s power. Plus, the TM 300 is a fast bike and doesn’t need much work to be competitive at that level.

And yet you started racing a 450 as an 18-year-old in Oz.

I’d say you learn quicker aboard a 450 because they bite harder if you get it wrong. There’s a lot more inertia and you need to overcompensate for that. If I had my time again, I wouldn’t have started racing a 450 so early because at that time, I still wasn’t getting the most out of a 250. Also, I think there’s less risk of injury on a 250, plus when you’re trying to get more out of a bike, you learn to become more creative and use the terrain to your advantage rather than just bulldogging it on a 450.

“On the days when I didn’t have the pace to get the job done, I wanted to make sure I was always up there to at least force mistakes from the other guys. And that strategy paid off in the end.”

When most Aussies take that huge step from racing in Australia to racing in Europe, they struggle to adapt to just how much more technical the terrain is in the World Championship. And then there’s all the other things – like language, food, culture – that they simultaneously need to adapt to. What was your experience with that transition to a foreign world?

At the ISDE, you can always see that Aussies riders have world-class speed. But you’re right; 70 percent of the game with racing the Enduro World Championship is being able to put yourself in an environment where you can thrive. When I look back at my energy-sapping virus in 2019, that was a result of all the stress I’d put on my body – all the travel and training and challenges of a completely new life on the other side of the world. I mean, back then as a 20-year-old, I’d never cooked a meal in my life. And then all of a sudden, I had to cook for myself. But there’s a lot more to it. It’s about learning to navigate relationships with Europeans, because language barriers can cause a lot of misunderstandings. And that can be a challenge when you’re trying to communicate what you think the team needs to do to improve the bike, for example. It requires constant evolution to be comfortable in your environment and to manage both the team’s and your own expectations.

And all those elements finally came together for you this season?

Yep. A lack of consistency has really worked against me for the past five years. I’ve been fast enough at most races, but I haven’t ever put a full season together. So, heading in the 2022 season, I made a conscious decision that at rounds where I found myself riding on the edge to take the win, I’d dial it back two percent and salvage the points rather than throw it away. Plus, I knew I was up against a stacked field in the E2 class. So, on the days when I didn’t have the pace to get the job done, I wanted to make sure I was always up there to at least force mistakes from the other guys. And that strategy paid off in the end.

You were also leading the EnduroGP Outright standings until midway through the year … until your bike dramas in Portugal.

Looking back at Portugal, I need to take some of the responsibility. I’d crashed in the extreme Super Test on the Friday night. My mechanic checked over the bike, repositioned the levers and fuelled it up and before putting the bike in Parc Ferme. But I didn’t communicate with him any detail about the crash. In my head, I was just thinking about putting the crash behind me, getting myself reset and just focusing on Saturday’s racing, when I knew I could make up the 10 seconds I’d lost. That’s because I like to approach my racing from an unemotional perspective – that is, I focus on the present and future, knowing there’s nothing I can do about what’s already happened. But in hindsight, I should have communicated with the team that my bike fell hard onto the right-hand side. Anyway, two minutes into the first special test on the Saturday, my throttle slipped off the end of the bars when I hit a big downhill G-out, and I went down hard. Friday night’s crash had obviously damaged the throttle assembly, but that damage wasn’t visible. If I’d mentioned it, my mechanic probably would have inspected the throttle more closely. Anyway, I was battered and bruised from the crash, but otherwise okay. But I just couldn’t get my head back in the game. I was trying to shake it mentally because I knew that weekend was an opportunity to get back in the hunt in the Outright points, but I couldn’t salvage what I needed to. I scored 5 points that weekend out of a possible 40 in EnduroGP, which is a big hit. At the following round in Slovakia, I went 1-1 in both the class and Outright and closed to gap to Verona in the EnduroGP standings to 9 points. But at the following round in Hungary, I had a spluttering engine issue on Saturday afternoon and got no points with a DNF. And that spelled the end of my chance to win the EnduroGP title. Which was a pity, because it could have been an awesome last-round showdown between me and Verona in Germany. That was a hard one for me to swallow. I couldn’t help feel a bit hard done-by because I’d done everything I needed to do and I’d lost a lot of points from things that were out of my control. That said, you can’t take anything away from Verona, either. He’s an amazingly talented rider and I have a lot of respect for how he constructs his championship campaign. And he executed it perfectly this year.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this interview with Wil Ruprecht in the coming few days…

Be the first to comment...