2013 Transmoto 450cc Motocross Bike Shootout

iKapture Images

iKapture Images

Honda CRF450R vs Kawasaki KX450F vs KTM 450SX-F vs Suzuki RM-Z450 vs Yamaha YZ450F…

2013 Transmoto 450cc Motocross Bike Shootout…

For 2013, the unchanged Yamaha goes into battle against an all-new KTM and much-updated Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki. But who got the 450cc MX bike recipe right this year? We unleashed the five machines on two very different tracks to unearth the black-and-white beneath their BNGs.

Can anyone truly claim to be colour-blind when it comes to motorcycles? No chance. Whether we’re aware of it or not, most of us have an almost innate preference for a particular brand of dirt bike; a brand that, for years, has been most clearly distinguished by the colour of its plastics. We like to think we’re a nicer ‘fit’ with that brand of motorcycle – often in spite of evidence to the contrary. The problem is, a predisposition toward a certain brand can ‘colour’ an otherwise rational assessment of which bike you ought to be laying down your cold, hard cash on.

You can see where we’re going with this, right? Yep, as an independent arbiter, we wanted to physically and metaphorically strip away any colour-based preconceptions and reveal the core character of the five bikes in this group test; to offer a ‘black-and-white’ insight into both their performance and the sort of rider and terrain each is most likely to suit.

Why a group test on the 450cc motocrossers? And why now? Because 2013 represents a fascinating juncture for these premier-class beasts. The 2013 KTM 450SX-F is an all-new machine that’s just won the AMA Motocross Championship. The Honda, Suzuki and Kawasaki all get sweeping upgrades for 2013, and all three are fitted with either Showa’s SFF or Kayaba’s PSF air fork for the first time ever. Meanwhile, amid all these overhauls, the Yamaha – the machine that’s won the past three Australian Motocross titles – has changed little more than its grip glue and graphics. Which makes it the perfect static benchmark against which the four new machines can be evaluated…

Before you continue, you may be interested in knowing the weight, riding style and bike set-up preferences of the riders who tested, scored and commented on each of the machines. For all of that plus information about the surfaces we tested on, the way the scoring system works, and a few technical specs on each of the bikes, click here.

If there’s one thing that defines the 2013 crop of 450cc motocross bikes, it’s the introduction of new technology into the bikes’ forks. Okay, the Yamaha’s 48mm Kayaba and the KTM’s 48mm WP forks are essentially the same units as the bikes ran in 2012, albeit with refinements to spring rates, valving and seals. But the 2013 Suzuki, Honda and Kawasaki all come with completely new forks – the RM-Z450 gets Showa’s 48mm Type 2 SFF (Separate Function Fork), while both the CRF450R and KX450F now come with Kayaba’s 48mm PSF (Pneumatic Spring Fork) air fork. Let’s recap each design…

Showa SFF

Amid a lot of scepticism, the 47mm SFF first appeared on the 2011 Kawasaki KX250F. Its right-hand leg contains the spring and the left leg looks after compression and rebound damping duties. The 23mm cartridge found on Showa’s conventional USD fork was enlarged to 30mm for the SFF, while the piston grew to 36mm for improved damping control. For the 2013-model RM-Z450 (and 2012 KX250F), the Type 2 SFF is an updated version of this design. The slider diameter is increased to 48mm and the internals are redesigned and inverted to improve damping control and effect. Yes, Showa has developed an SFF Air Fork (where nitrogen replaces the steel spring), which has been exclusively used and tested by Pro Circuit in America over the past two years. Rumours suggest it’s likely to appear on the 2014-model RM-Z450. Given that Kayaba have led the industry in recent years with their AOS (Air Oil Separate) twin-cartridge forks, it makes sense that Showa strike back in the air-suspension development race.

Claimed benefits:

- Reduces weight by 1kg and stiction by up to 25%.

- Smoother action and firmer damping performance.

- Isolating the damping to the left leg frees up space for a spring preload system in the right leg with a large range of external adjustment to tune the front-end’s ride height.

- Right-side fork spring offsets the weight of the left-side brake disc and caliper.

- Reduces unsprung weight by 800g and stiction by up to 20%.

- Increased sensitivity to small bumps and more linear action through the stroke.

- Creates a quick and easy, stepless adjustment of ‘spring rates’.

- Stronger bottoming resistance and a wider setting range.

- The air can be completely removed to lower front-end for transport.

- Damage to the chrome sliders and fork seals can let the air pressure escape, and cause the fork to collapse. This happened to one Kawasaki rider at the recent A4DE.

- Heat build-up over the course of a moto effectively means that the fork’s spring rates get progressively firmer. During our testing, air pressures in both the Honda and Kawasaki PSF increased by 4 to 6psi in the space of half an hour. That’s equivalent to two to three spring rates.

Added adjustability is always a good thing, and we spent some time dialling more spring preload into the RM-Z450’s SFF during our testing to get the fork to sit up better in its stroke and to settle the bike’s front-end for high-speed corner entries.

Kayaba PSF

Since the start of the year, there’ve been rumours that Kayaba was working on an air fork, but it came as a surprise that the PSF was fitted to Honda’s and Kawasaki’s production bikes for 2013. Externally, the PSF appears very similar to the Kayaba AOS (Air Oil Separate) fork that both the Honda and Kawi used in 2012, but internally, it’s much different. The conventional steel spring in each fork leg is replaced by air, but the fork retains the same inner- and outer-chamber oil baths. The cavity where the springs used to sit is redesigned and sealed to hold compressed air, with the air pressure adjusted by a Schrader valve in each fork cap. An increase in pressure from 32 to 40psi equates to going from 4.6 to 5.0N/mm fork springs, with 2psi increments roughly the same as one spring rate. As the inner chamber no longer needs to fit inside a steel spring, the inner diameter of the chamber and its damping piston grows from 28 to 32mm, theoretically meaning much better damping control. It’s rumoured that Kayaba’s PSF will appear on the 2014 CRF250R and 2014 or ’15 YZ450F. Yamaha, who own Kayaba, claims that the bike’s frame needs to be totally redesigned for the PSF, so they will not use it with the current-frame bikes.

Claimed benefits:

All of which makes a lot of sense. And there’s no doubt that the ‘spring rate’ adjustability made it very quick and easy to set up the 2013 Honda and Kawasaki fork to suit test riders of different weights or varied track conditions. But we still have some reservations about the PSF. Namely:

Ergonomics

With its all-new bodywork, sixth-generation frame and lower centre of gravity, the 2013 CRF450R looks and feels like a physically smaller and more compact machine than the other four 450s, and it tipped our scales as the lightest bike at just 106.8kg (fluids, but no fuel). Even its wheelbase appears short and, on first inspection, several testers actually thought Honda had accidentally sent a CRF250R along to the test. When you sit on the bike, those compact dimensions are confirmed. Its seat is noticeably lower than the other four bikes and, in the attack position, the average 180cm guy will be able to get the entire souls of his boots flat on the ground. Sit the same way on the other four machines, and only the balls of your feet will touch. Given the low seat, the bars feel tall, and they’re positioned very close to the rider, too.

So, while the new streamlined bodywork (with built-in lift points and the slimmer radiator shrouds) is a positive move, the new bike’s ergos certainly aren’t conventional nor easy to get used to. Taller guys will feel cramped while seated and as if they’re hanging off the arse-end of the bike when standing. Interestingly, we noticed that the 2013 CRF450R Chad Reed debuted at the recent Australian SX Championship had the front of its seat built up significantly to create a set-up he’s more familiar and comfortable with. And Chad’s not a tall guy. The good news is that the tiny 5.7 litre fuel tank has grown to 6.3 litres for 2013, which’ll take the stress out of those long motos in the sand. But because more tank now sits above the frame’s twin spars (which now meet the head tube noticeably lower), its black plastic gets scratched up very quickly. No biggie, as aftermarket decal kits are likely to address this.

And maybe there is something in Honda’s application of the “ultimate triangle proportion” design philosophy to their CRF range, because the majority of testers reckon the Honda is, hands down, the coolest looking motorcycle of the bunch. Though its rear guard and sideplates sure seem to have borrowed from the KTM.

Power Delivery

Like its ergos, the Honda’s powerplant also has a noticeably different feel to the other four machines. For starters, its exhaust note is so quiet, it’s hard to believe you’re aboard a 450. Which is a good thing, of course. What’s not so good is that the 2013 CRF feels conspicuously down on low-rev torque and throttle response compared with the other four 450s. And that’s strange because it flies in the face of what Honda’s PR material says. For 2013, the engine mods (higher compression ratio, straighter inlet tract, new inlet and exhaust valves, flowed head, etcetera) have all been aimed at bolstering the CRF’s bottom and mid-range power – by a claimed 10%. So how do you reconcile Honda’s brochure with our real-world experience? We can only assume that any power gains at low revs have been more than offset by the combined effect of the heavier flywheel, six-spring clutch and dual-muffler exhaust – all of which are fitted for the first time this year.

We’re not saying that taking the sting out of the Honda’s bottom-end is necessarily a bad thing – because, on hardpack, the Honda’s power is fantastically user-friendly and it’s the easiest bike of the bunch to get hooking up. Even without short-shifting or super-precise throttle application, the Honda’s rear wheel doesn’t feel like it wants to constantly light up and step out on you, and it’s the least fatiguing bike of the bunch

to ride for long periods.

On sandy tracks, however, the new engine’s lack of punch at low revs takes away from its versatility. You need to set up earlier for turns, get on the gas before the apex and carry more corner speed. Because if you come in hot, bury the bike in the berm to wash off speed and blast out with the throttle, the Honda demands more clutch to keep it in the meat of the power. While the engine’s transition from bottom to mid is very smooth and there’s plenty of mumbo through the mid-range, it definitely falls off the power quicker than last year’s bike at high revs – which we reckon has more to do with the restrictive exhaust than the engine itself. At high revs, the CRF450R’s exhaust gases literally sound like they’re fighting to escape from an enduro bike’s exhaust system.

Sure, the “twin rhombohedral muffler” looks cool, helps centralise mass and makes the Honda quiet as a church mouse, but we’re not sure those benefits outweigh the negative impact it has on the breadth of CRF’s power delivery for 2013. The dual muffler lasted three years on the CRF250F before it was finally scrapped for 2010, so it’ll be interesting to see what sort of lifespan it has on the 450. This smoother style of power delivery definitely makes the 2013 Honda less intimidating for the average punter, especially on the hardpack tracks we get on the east coast of Australia. But if you’re a heavier guy who rides loam and sand or a Pro whose style revolves around having plenty of punch on tap from low in the rev range, the 2013 Honda is probably going to feel too sanitised. That said, a more free-flowing exhaust system is likely to bring the Honda engine to life – especially up top – and broaden its useable power delivery.

Handling

Getting a dirt bike to turn well in tight terrain and yet remain stable at speed is the Holy Grail of any chassis and suspension package, but finding a happy medium is never an easy task – especially with an all-new chassis. To our way of thinking, Honda’s all-new sixth-generation frame focuses too heavily on slow-speed steering at the expense of high-speed predictability. Thankfully, the 2013 450R has completely lost that stinkbug feel of its 2010 and ’11 predecessors. Its chassis now feels a lot more balanced, but it hasn’t given away the trademark steering accuracy, even on slick hardpack. If you load up the front-end in tight ruts or flat turns, the machine turns without a moment’s hesitation. Combine that with the compact chassis dimensions and the Honda has the most agile, flickable feel of all five bikes. You can throw the thing around in the air like a 250, square off corners and get the bike into and out of slow-speed turns incredibly well. All of which will make this chassis a weapon around a supercross track.

But on fast sections of a motocross track, the Honda is harder to get settled and just doesn’t feel planted to the ground. The short wheelbase feel that makes it so nimble, works against the Honda when you start to hit high-speed bumps. That makes you feel like you need to grip the bike a whole lot harder with your legs to keep the thing tracking straight, especially over a series of square-edged bumps, where the Honda tends to see-saw more than the other four bikes, too. Adding a few psi of air pressure to the PSF helped settle the chassis and create a more stable, predictable ride at high speed without affecting the low-speed turning too much (which is the beauty of this new air fork). But on both the sandy and hardpack test tracks, Pro riders still complained that they struggled to push the Honda as hard as the other bikes at speed without feeling like it was going to bite them. The suspension action itself is excellent. It’s not as plush at either end as the Kawi – which runs very similar Kayaba fork and shock – but the Honda’s PSF, in particular, soaks up the small bumps noticeably better than last year’s CRF.

Frame and Fork

For 2013, the all-new 9.35kg “sixth-generation” twin-beam frame is designed to centralise mass and lower the C of G, and check out just how much lower the twin-beam spars meet the head tube. Kayaba’s all-new PSF (Pneumatic Spring Fork) is fitted for the first time. It’s claimed to be 800g lighter and 20% less sticky.

Engine

To deliver a claimed 10% boost in low to mid-range power, the engine gets a reflowed head, new inlet ports (3% more flow), larger exhaust valves (30 to 31mm) and more compression (12 to 12.5: 1). That’s married with an 11% heavier flywheel and all-new six-spring clutch. The footpegs are now 10% lighter and 5mm further back, too.

Bodywork and Exhaust

To complement the new frame, the bodywork is slimmer and more streamlined. It comes with reinforced attachment points, built-in lift-points on the rear fender and a larger 6.3 litre fuel tank (up from 5.7). Yep, that’s the “twin rhombohedral muffler” design. It produces a very quiet exhaust note, but feels to be very restrictive.

Ergonomics

With the major chassis and bodywork upgrades taking place on the 2012 KX450F, the 2013 Kawi cockpit doesn’t offer up too many surprises – aside from the fact you now look down on an all-new Kayaba PSF air fork with a Schrader valve in each leg’s cap, plus a slightly different (push-rod type) front brake master cylinder. And, yes, the front number plate and rear guard are now white to imitate Ryan Villopoto’s AMA SX-winning race bike.

The KX450F has a spacious feel to its cockpit. The seat is comfortable without being cushy and all controls fall perfectly to hand. It’s not quite as slim through the girth as the Suzuki and Honda, and in the attack position, you do tend to sit a little further back in the Kawi’s saddle. But the green machine has really benefitted from the slimming program it underwent last year and it no longer feels like the oversized beast it did in 2011. Most test riders rolled the bars back a little from standard for the most comfortable seat/peg/bars triangle, and a few of the taller guys opted to lower the footpegs by 5mm for more legroom.

While the other four machines all come with adjustable handlebar positions (as they should), the Kawasaki also gets adjustable footpeg positioning and a Launch Control Mode button on the bars – the only bike to have either. And when you consider it’s also got the plug-in DFI couplers to adjust engine mapping and the infinitely adjustable new PSF air fork, the Kawi certainly stands out as the machine most capable of being customised to suit rider preference and track conditions. And who’s going to quibble about that?

Power Delivery

Wow, what a donk! This thing is new-generation, fuel-injected four-stroke technology at its best. Let’s come straight out and say it: our test riders unanimously scored and rated the Kawasaki’s powerplant as the strongest and most versatile of the five bikes. It has the broadest spread of useable power and the smoothest delivery, and yet remains incredibly responsive to throttle inputs right across the rev range. As with the 2012 Kawi, the meaty mid-range is where this engine really shines, but with more bottom and top-end for 2013, it’s got an even more refined feel about it.

The revisions to piston, ECU and inlet cam have combined to make a great engine even better – mainly by improvements to response at low revs – and asking test riders to single out a weak area with this powerplant was like pulling teeth. Okay, with so much throttle response and sheer grunt on tap, the KX-F’s rear-end could feel pretty lively on the skatey hardpack. After all, it’s a 450 with some 50 horsepower. But the green machine has an answer to this, too. Simply swing by the pits, plug in the DFI coupler with a soft map, and the Kawi becomes a noticeably more user-friendly beast. The power is still all there when you get into the mid; it’s just more forgiving for a given throttle input, which helps you get the bike turned, upright and pointing in the right direction before it gets into its stride. The most impressive thing about this engine is its torque, which is perfect to get you out of trouble if you get caught in a too-tall gear, even in power-sapping sand. But in terrain where traction is at a premium, the delivery is still smooth and predictable enough to get the rear-end hooking up and driving. There’s no crazy, abrupt hit off the bottom; just a seamless surge of grunt that does exactly as your right hand instructs it to.

Once she is driving, you can hold gears forever. Like its predecessor, this engine keeps making power right through to the rev limiter. And it’s this incredible breadth of power that lets you get away with fewer gear changes around the average motocross track. It’s a lazy man’s short-shift bike and a Pro rider’s race weapon in the one package, and quite possibly the most versatile and faultless engine we’ve ever tested. We mucked around with the Launch Control Mode by doing several race starts on the hardpack track. And while not everyone was convinced it created better drive out of the gates, no one was prepared to say it hindered their starts. What the repeated starts did bring home was that the Kawi has the loudest exhaust note of the bunch. It’ll be interesting to see if the MA noise meters think the same. But in any case, all the work that Kawasaki engineers reckon they’ve done to the muffler to make this year’s bike quieter, doesn’t make it any less obnoxious on the human ear.

Handling

With such an impressive powerplant, big questions are asked of the chassis and suspension to get the power to the ground. And it delivers – across all terrain types and at high or low speed. While the Kawasaki is not as firmly sprung as the KTM, it does still feel to be one of the firmer machines, and it’s well balanced from front to rear. The second you hit your first square-edged bump on the track, it immediately strikes you just how plush a ride the Kayaba fork and shock deliver. Over the small, choppy bumps, the KX-F has the most compliant, unflappable ride of all five bikes. The fork shows no hint of deflection off square edges, while the shock squats nicely under both brakes and acceleration and gives the rear-end a planted, predictable feel that rarely kicks sideways. With both ends working so well, the Kawasaki was the easiest bike to ride aggressively on the hardpack test track.

Because of the plush ride over the small bumps, you actually expect the fork and shock to blow through their stroke the second you hit your first decent jump. But they don’t. In fact, they won’t. The progression in both fork and shock is so good that no test rider bottomed-out either end of the Kawi during our two-day test. Given how smooth the ride is in the first part of the stroke and the calibre and weight of our fast Pro test riders, that’s really saying something.

In fact, once we established the bottoming resistance was so good, a few test riders got the confidence to let 2-3psi out of the PSF because, unless you were really driving the front wheel into turns and/or dragging some front brake through shallow ruts to keep the front wheel planted, the Kawi’s front-end could start to feel a little vague in the mid-turn. In the tight turns, less air pressure helped the fork sit down into its stroke and offer better feedback, without compromising high-speed stability. But the Kawi isn’t a stop-turn-point-and-shoot bike. It actually works better if you keep the thing flowing through corners and is better suited to riders who like to rear-end steer the bike rather than rely on planting the front-end and turning around that.

Kayaba PSF

Aside from being lighter than its 48mm AOS-type predecessor, Kayaba’s new Pneumatic Spring Fork is designed to deliver a more sensitive ride over small bumps. It also allows you to quickly and easily adjust the fork’s ‘spring rate’ via air pressure changes. Like the Suzuki, the Kawi comes with two couplers to alter engine mapping.

Powerplant

The 2013 engine gets a new bridge-boxed piston, new ECU settings and revised intake cam profiles – all of which are to generate more response through the bottom-end and mid-range. The new bike drops the black engine covers in favour of silver pained specimens. And to protect the cases, the KX-F runs a hard plastic skidplate.

Rear Guard

White rear guards, eh? First Honda, then KTM and Yamaha, and now Kawasaki for 2013. It’s designed to imitate the factory machine Ryan Villopoto won the 2012 AMA Supercross Championship aboard. Internal muffler mods and noise-absorbing pads are claimed to produce a quieter exhaust note, but we’d not sure they’ve worked.

Ergonomics

If there’s a landmark model that KTM hopes will finally act as a springboard into the lucrative American motocross market, then this is it. And the Austrians are off to a pretty damn good start with the thing, too. After Stefan Everts convinced KTM’s big brass that a rising rate linkage was virtually a rite of passage into the American market, the design concept got a new lease on life when Roger DeCoster and Ryan Dungey were reunited under the orange big-rig late last year. With a bottomless pit of funding from KTM HQ, the two fast-tracked the development of a bike that allowed Dungey to finally deliver the European brand the Holy Grail of MX earlier this year – a premier-class AMA Motocross title win.

So there are no surprises that, of all five bikes, the 2013 KTM represents the most radical change from its predecessor. The interesting thing is that those changes give the machine and its ergos a more conventional – dare we say it, Japanese – feel. Sure, it’s the only bike with a chromoly frame and the only one that doesn’t run Kayaba or Showa suspension and Nissin brakes, but this latest 450SX-F is certainly nowhere near as ‘foreign’ as it was a few years back. The new Kato is a faction wider though the girth than the super-slimline Honda and Suzuki, but not badly so. And its bars a little taller than average, too. But the seat/bars/footpeg triangulation is now difficult to distinguish from the Japanese bikes when you’re sitting on the machine at rest. Strangely, for a brand that was once synonymous with rock-hard seats, the 450SX-F runs the softest seat of the bunch. It’s lovely on the lolly-bag, but is at odds with the hard-nose race-oriented swagger the rest of the bike exudes. And it means you have to put a little more effort into sliding forward and back in the Kato’s saddle.

The other standout thing about the KTM’s cockpit is that its controls have a light, smooth and precise feel to them. The Brembo hydraulic clutch has a noticeably lighter pull, too. And, of course, it’s the only bike

of the bunch to come with an electric-start. It may add a kilo or two to the bike, but that’s something most of us would be willing to put up with for the convenience it offers.

Power Delivery

As the 450SX-F’s SOHC engine is derived from the powerplant that first appeared on KTM’s 2012-model 450EXC, it’s easy to assume it was KTM’s intention to build a smooth, enduro-style motor for their all-new motocross bike. Not so. Differences to cam profiles, head porting, valves, EFI mapping, throttle body, transmission and exhaust combine to transform the EXC’s donk into a responsive, super-powerful beast in the 2013 450SX-F. And the KTM delivers the strongest mid-range of all five bikes.

It’s the sort of free-revving, relentless power that laps up loamy or sandy conditions and, with little or no clutch use, it’ll explode out of turns – even if you get caught in the wrong gear. In slick terrain, however, it can feel too responsive at low revs, even for experienced riders. It doesn’t hit like a hammer off the bottom, but with absolutely no lag between the throttle and the rear wheel, the KTM tends to light up if you’re not careful on hardpack, and most test riders found it was much easier to short-shift the Kato if they wanted to get its rear wheel hooking up smoothly on corner exits. Coming out of turns where the other four bikes ran

second gear, the KTM happily pulled third. Which is a good thing because running taller gears take some sting out of the Kato’s mid-range hit. With such an incredible mid, you’re better off getting the bike pointing the right direction before opening the taps. Like the Suzuki, the Kato signs off a little earlier than the Yami and Kawi at high revs, so it’s all about exploiting that prodigious mid-range. With its seemingly short 13/52 final drive ratio, we reckon the Kato would benefit from slightly taller gearing (a 51 or 50-tooth rear sprocket). It’d help smooth the transition into the mid, and broaden the useable range of both second and third gears. And if ever there was a bike that’d benefit from a bar-mounted soft-option EFI map, this 450SX-F is it.

The other notable trait with the KTM is how much more engine braking it has than the other four bikes. Average riders generally don’t mind this, as it helps anchor the rear-end on the way into turns and takes the emphasis off perfect brake application, but Pros tend not to like it as it throws more weight onto the front-end heading into turns. And it did take everyone a few laps to adapt to the KTM on the sandy test track for this reason.

As the only bike with a hydraulic clutch, the KTM’s lever pull is way lighter than its cable-operated rivals. It’s a one-finger job all day, and it does have a distinctly different feel to it. With a quicker take-up than the cable clutches, it’s very much an ‘on or off’ affair. That’s great for starts as it creates a precise connection between throttle hand and rear wheel, but for riders accustomed to the progressive modulation of a cable clutch, it’ll take a little getting used to.

Handling

Not only is this all-new 450SX-F substantially lighter than its predecessor, its engine also has much less gyroscopic forces, and this pays big dividends in the handling department. The new bike is so much easier to flick from side to side or to pull back into line in the air, and there’s none of that tendency for the thing to want to stand up on corner exits. The entire chassis has a much more balanced, neutral and agile feel. In contrast to its soft seat, the KTM’s suspension is firm at both ends, and that gives the chassis a very race-oriented character that almost insists you ride it hard at all times. The WP fork doesn’t have as plush a ride as the other bikes’ Showa and Kayaba forks over the small bumps, but it doesn’t deflect, either. It just gives you a very direct and raw feel for the terrain being processed under the front wheel.

The KTM’s suspension really starts working nicely in the mid-stroke. The harder you push the fork and shock, the more they stand up to the abuse and the better this bike feels to ride. You can’t dawdle around, hoping the suspension will do the work for you; the WP fork and shock like you to commit and hit obstacles like you mean it! On braking bumps, the fork sits up beautifully in its stroke and creates a super-planted ride. And no matter how hard you drive the thing into bumpy downhill corners, the Kato delivers by far the most confidence-inspiring front-end feel of all five bikes. That’s complemented by a very anchored and settled rear-end, which squats nicely because of the added engine braking.

In fact, the only shortcoming we could find with the KTM’s suspension comes in the mid-turn. When you’re off the brakes and rolling through the mid-part of the turn, the firm fork can feel a little vague and this left some test riders looking for more feedback from the front wheel. Also, on bumpy corner exits where there isn’t a lot of traction, we found the KTM is more sensitive to the rider’s weight distribution. Once you learn to shift your weight back in the saddle and get the shock to sit further down into its stroke, the rear-end hooks up and tracks noticeably better. It’s the one handling trait that really sets the KTM apart from the Japanese bikes.

Powerplant

The EXC-derived 450SX-F donk uses the same bottom-end, bore and stroke and DDS clutch as the enduro bike, but it gets an MX-specific five-speed transmission, a 44mm bottom-mounted throttle body, and different cam profiles, head porting, valves, mapping, and exhaust. And it’s the only 450cc MXer with an electric start.

Bodywork

KTM turned the MX world on its ear when they released their 2010 350SX-F – not just because it was the first new-generation mid-capacity MX machine, but because the bodywork was so futuristic. The 2013 450SX-F takes that theme even further, with refinements to the shape of the shrouds, sideplates and guards.

Rolling Chassis

For 2013, the chromoly frame gets reinforcements around the steering head for torsional rigidity, thinner cradle tubes to save weight, lighter triple clamps and a new ‘moon-dust’ metallic silver paint. The rear wheel gets a 5mm larger rear axle (up to 25mm) and black-anodised spokes for increased durability.

Ergonomics

All five test riders adapted to the RM-Z450’s ergos quicker than any other machine; so much so that they all reported being comfortable enough to get stuck into it on just their opening lap aboard the Suzuki. Controls fall perfectly to hand and there’s nothing on the frame or bodywork to catch your boots or impede your movement back or forward in the saddle. Of all the bikes, the Suzuki has the slimmest girth and the flattest, firmest and narrowest seat, which gives it a very race-spec feel out of the crate and, like the Yamaha, you sit tall on the RM-Z450. With its lowish and slightly swept-back bars, the Suzi’s seat/pegs/handlebar set-up puts you in a very commanding position in the cockpit – your head is so far over the front of the bike, you’re actually looking down over the fork caps and staring the front number plate in the face. In other words, the neutral position on the Suzuki’s seat effectively becomes the attack position, and this alone insists you ride the bike with attitude and aggression.

The other unique thing about the RM-Z is its cool alloy fuel tank. You’ve got to like the idea of alloy over plastic and it’s got that factory-bike look. But when was the last time you heard of a plastic tank splitting? And doesn’t an alloy tank make the fuel more susceptible to getting too hot and vapourising? After all, that cost Ryan Dungey and Suzuki an AMA Outdoor championship last year. We were also surprised that the Suzuki weighed in as the heaviest bike of the bunch, because it sure doesn’t feel heavy when you’re riding it. At 110.7kg, the RM-Z is almost 4kg heavier than the Honda, even though it doesn’t run a battery and electric-start hardware like the 109.3kg KTM does.

And, yes, we need to say something about the colour combo used for the new plastics. While everyone was frothing over the edgy, cool look of the new Honda, the Suzuki’s move to a yellow front plate and black rear guard wasn’t exactly a catwalk hit with the boys. Admittedly, it’s a minor point, but who wants to take a brand new bike home from the dealer that looks like it’s been fitted with plastics off your little brother’s FMX bike? At least the 2013 RM-Z450 will keep the aftermarket graphics guys busy.

Power Delivery

If there are two bikes with the most similar power curves, it’s the Suzuki and Kawasaki – the only real difference being that the RM-Z450 doesn’t quite pull as hard all the way through to its rev limiter. Meaning, unless you’re a Pro rider who’s wringing the bike’s neck through the top-end before every gear-shift, the Suzuki offers a really broad and confidence-inspiring style of power that combines excellent throttle response with user-friendly tractability. It’s as if the engine is now more responsive – care of the 13% lighter piston – but the mods made to the inlet tract, camshafts, ignition, exhaust system and air boot offset it and ensure the engine doesn’t spin up too fast. The RM-Z450 is exciting to ride without being overly aggressive, and that makes it a very versatile engine for a wide variety of terrain.

There’s plenty there to light the rear wheel up in power-sapping sand, and yet the delivery is smooth enough to dial it on and get the rear tyre hooking up in slick terrain. Like the Kawi, the RM-Z has a couple of pre-mapped plug-in coupler (a lean/aggressive and rich/mellow) options, which only adds to the bike’s all-round usability. On the hardpack track, the rich coupler helps take the sting out of the throttle response at lower revs and definitely gets the power to the ground more effectively on the slicker sections of the track. The rich map also makes the bike easier to ride when you get tired and your throttle control gets a little wayward. We also tried the lean (aggressive) coupler on the sandy test track, but didn’t notice an appreciable difference. What is noticeable for 2013, though, is that the mods to header pipe, muffler and the fibre composite patch that now sits on the rear of the airbox all combine to make the exhaust note significantly quieter to ensure the bike meets the new, more stringent FIM noise regulations that Australia is expected to adopt for 2013 – albeit it on very late notice from Motorcycling Australia! Our only real gripe with the Suzuki’s powerplant is that it has the heaviest clutch pull of the bunch. Perhaps their engineers can use this as an excuse to be the first of the Japanese bikes to move to a hydraulically operated unit.

Handling

The magic of the Suzuki is that its ergos and chassis complement each other so perfectly – in tighter corners anyway. With a seating position that puts you right over the front of the bike and a chassis that likes the rider loading up the fork, the RM-Z is one of the best-turning bikes of the bunch with the front-end giving you plenty of feedback before it lets go. That makes it fantastically easy to get in and out of tight corners and rutted turns on the RM-Z, and it’ll change lines mid-turn with very little rider input. On the sandy test track, you could just sit over the front of the bike and tell it to go anywhere you want. The chassis seems to have a really broad and forgiving sweet spot when it comes to the rider’s weight distribution. And irrespective of the terrain, the chassis retains a composed, balanced and neutral feel through the middle of the turn.

As capable as the Suzuki is in the slower, tighter corners, most testers were a little un-nerved by the bike’s front-end feel at high speed on the way into turns – just as they transition from the throttle to brakes. On the hardpack test track, the Suzuki’s SFF has a tendency to sit down into the harder portion of its stroke and dance around when you punch into a series braking bumps. If you’ve got the bike cranked over at the time, that lively fork action makes it difficult to hold your line or, in worst-case scenarios, inclined to tuck. We improved the RM-Z’s front-end in these situations by giving the fork more spring preload and less compression damping. But we still couldn’t get bike’s front-end to feel anywhere near as settled and sure-footed as the Kawi’s or KTM’s under brakes. Once into the corner, the Suzuki resumes its planted feel, and on corner exits, the bike’s shock absorber works an absolute treat. Under acceleration, the rear-end squats and drives beautifully. And on high-speed bumpy straights, the RM-Z takes a lot to knock it off line and it tracks as straight as any bike.

Showa SFF

The RM-Z450 is the only bike to run Showa suspension and for 2013, it gets the 48mm Type 2 SFF (Separate Function Fork) – a much-updated version of the fork that first appeared on the 2012 KX250F. While the SFF offers a

wide range of spring preload adjustment, we have some question marks over its damping character.

Powerplant

Mods to the fifth-generation engine were aimed mainly at improving throttle response and mid-range power and torque. The piston is 13% lighter and comes with a DLC coating. The 2013 engine also gets mods to camshafts, ignition coil, exhaust system and air boot, and two plug-in FI couplers to alter the mapping.

Inlet Tract

You’ll notice the new air boot has two inlet ports. The upper one directs air to the throttle body while the other one is actually a ‘dead-end’. It’s specifically designed to add 60ml of air volume to the bike’s inlet tract and tuned to create a pressure wave that’s claimed to improve EFI efficiency, horsepower and torque at low revs.

Ergonomics

A few years back, who’d have thought we’d be referring to a Yamaha as the most foreign feeling machine in a group test? It’s true that Yamaha has built a reputation for bringing revolutionary technology to market, but the company is also notoriously conservative in many respects. And by leaving the ergos of the YZ450F essentially the same for the past four year-models, convention has moved elsewhere in the meantime. While the rest of the manufacturers have scrambled to make their motocross weapons slimmer, lower and lighter, the Yamaha now looks like a Clydesdale in a room full of sinewy thoroughbreds. It’s visibly broader through the girth, the junction of its seat and tank, and the radiator shrouds – which is magnified by the fact its big shrouds are convex rather than scalloped out like the other bikes to accommodate your knees while sitting. The result is that you feel like you’re perched up on the Yami’s broad shoulders.

And so it came as some surprise that, at 107.6kg, the Yami remains one of the lightest bikes in the class. What was interesting is that the biggest issue for testers was staying forward on the bike, as the fat fuel tank and flared shrouds tend to spread your legs and force you back in the saddle through tight corners. That can be a real problem for slower turns where you need to weight the front tyre to turn off it. Despite the bike’s exaggerated dimensions, there’s actually less legroom when seated on the YZ-F than the other bikes because its footpegs are mounted so high on the frame. The shortened peg-to-seat distance can take a while to get used to when standing on the bike, too.

Power Delivery

Like the ergos, the YZ450F’s powerplant also produces a very different feel to the other four bikes, the most obvious of which is the audible induction noise emanating from under the tank where its air filter is situated. It’s a bit of a distraction to begin with and can make it difficult to get a feel for where you are in the rev range and when to upshift. But once you get your ear tuned to the unusual exhaust note and a feel for the sweet spot where this engine likes to be shifted, it can be used to great effect in soft or hard terrain. The YZ-F produces plenty of torque from right down low in the rev range and doesn’t mind being short-shifted and laboured in the slightest. Through the mid-range, the reverse-cylinder engine produces a broad, strong and torquey surge of power. In its own refined and vibration-free way, it winds up more progressively than the Kawasaki, Suzuki and KTM as you dial the throttle on, which makes it pretty forgiving if there’s not much traction on offer. It takes a few laps to realise it, but this engine actually does a very efficient job of getting the power to the ground and driving the bike forward, rather than simply making noise, spinning up and going nowhere.

For that reason, it’s a deceptively fast powerplant. But we reckon it also has a couple of shortcomings that are now starting the reveal themselves because the Yami’s rivals have raised the bar in recent years. First, the YZ450F falls off the power fairly abruptly at higher revs, and this can upset the way the rear-end tracks over bumpy ground if you’re not expecting it. And second, its EFI is very lurchy right off the bottom. It’s not a problem when you’re driving out of slow-speed ruts – and its something you’ll never feel on a sandy rack – but it does make life very difficult when you’re trying to gently trail the throttle and stay smooth all the way around a long, bumpy, constant-radius hardpack sweeper. Something in the Yamaha’s brain demands an ‘on or off’ signal from the throttle department, and its almost impossible to feed the power on progressively right off idle. For a bike with so much mumbo and go-forward, this really should have been addressed as most bikes’ EFI teething problems are now a thing of the past.

Handling

There’s no denying the Yamaha handles as you’d expect it to: like a big, tall, single-minded animal that’s hard to knock off line and which needs noticeably more manhandling to wrestle it from side to side. Spring rates at both end are firm and beautifully well balanced from front to rear, and while its ride is not as plush as the Kawasaki over the small, choppy bumps, the Yamaha’s chassis has a super-stable feel. The thing held its line better than any other bike through a series of high-speed hits on the choppy hardpack test track, and no matter what sort of square-edged bumps stand in your path, the Yamaha gives you the confidence to relax in the saddle and take them on. While that sort of predictability is good news for most of us, it’s not necessarily music to Pro riders’ ears. Everything happens so slowly on the Yami that experienced riders often want more feel for what the chassis is up to, particularly in the front-end.

The Yamaha is at the opposite end of the stability scale to the Honda, but then again, it’s nowhere as agile in the tight going. As the very upright engine configuration places less weight over the front wheel,

the YZ-F doesn’t steer as quickly as the other four bikes through tight ruts or slow-speed corners, and it doesn’t have the planted and predictable feel in the front-end on skatey surfaces – some of which is probably the result of the difficulties in getting forward in the saddle. In any case, you can end up wrestling the bike’s front-end to place it where you want it, both on the way into turns and in the middle of the corner to ensure it holds its line. Unless you get aggressively forward in the saddle or trail the front brake the keep the fork a little compressed, the Yami’s front wheel has a tendency to climb up the rut walls. Less compression damping does give the Kayaba fork more mid-turn feel and traction in the slower turns, but it also upsets the chassis balance and the bike’s trademark stability at speed.

What became patently clear after a day on the hardpack track is that the Yamaha doesn’t work well as a point-and-shoot bike. You can’t afford to be lazy on the Yami and steer the bike with the front-end. It responds much better to sweeping lines and a rider who knows how to steer the thing with his throttle hand.

Powerplant

Mapping and ECU aside, the Yamaha uses essentially the same reverse-mounted, fuel-injected engine that shocked the motocross world when it first appeared in 2010. For 2013, the barrel gets an updated Electrosil treatment for added durability. But aside from that, the 2013 powerplant remains unchanged.

Handlebars

To match the YZ450F’s black rims, the silver handlebars are now black, Yamaha-branded tapered units for 2013, and they’re dolled up in a carbon-look crossbar pad. The rear mud guard is now white, and word on the street is

that the 3M glue for both grips and the bold new graphics is also different … and lighter!

Shock Collar

Because technicians spend half their day at a group test winding the shock preload on or off to get the bike’s ride height right for testers of differing weights, this nifty aftermarket X-Trig preload collar was fitted. It’s there simply to expedite the task of preload adjustment and has no impact on the shock’s performance.

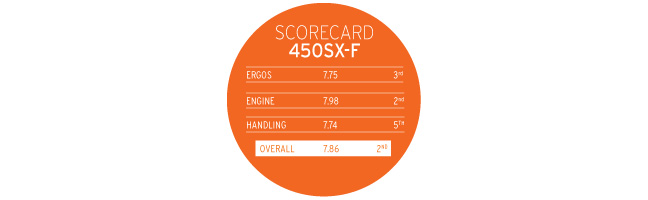

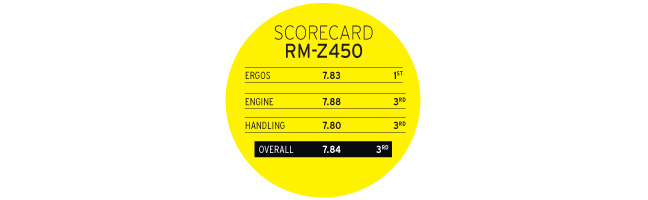

If there’s one thing we can impress on you here, it’s that you shouldn’t place too much emphasis on the rankings for each bike. Why? Because the scores were so incredibly close. In many instances, three or four bikes are often only separated by just 0.2 of a point (out of a possible 10), so it’s important that you put those scores in context by referring to both the test rider feedback and the insights they offer into their riding style and bike set-up preferences on page 50.

Yes, the Kawasaki was an incredibly strong performer. It did everything well and nothing badly, and was the clear winner in both engine performance and handling on most riders’ scorecards. But what would it take for the other machines to take on the green bike in the overall stakes? The KTM would need better feel from its suspension and a more tractable power deliver. With a fork that performed better on high-speed braking bumps, the Suzuki would have been right there in the Kawi’s face, because it was a match for the KX-F in most other areas. And with more user-friendly ergos and better feedback from its front-end, the Yamaha would also be right there in the hunt. The Honda, on the other hand, was never really in the picture. And that surprised us. Despite being incredibly compact and nimble, this all-new machine just doesn’t have the breadth of power nor chassis stability to get near the other four machines. Not this year anyway.

Best bike in sand…

Luke: Kawasaki and Honda. Being able to add air pressure to the fork let me get both bikes set up tall in the front how I like them in sand. And their motors worked for the way I like to flow around corners, rather than coming in fast, burying the bike and powering out.

Beau: The KTM and Suzuki. When the bike wants to go everywhere in rutted sand, those two bikes felt the most stable. And their strong bottom-end power let me steer them with the rear-end.

Josh: The Suzuki, with the Yami and Kawi very close to it. The RM-Z just turned so well and I felt really comfortable to push it hard.

Mark: Suzuki and KTM. On a tough track that was hard to ride, their balanced chassis and torquey engines made the job easier.

Phil: The KTM. The fork and shock sit up in their stroke and there’s so much torque, response and mid-range to help you steer the thing with the power and put it where you want it.

Best bike on hardpack…

Luke: The Suzuki and Honda. They both turn so well and give me lots of feedback and feel in the front-end – and that suits a guy like me who always rides over the front of the bike.

Beau: The Kawasaki. Even though the track was really bumpy and skatey, it let me attack everywhere and still did exactly what I wanted it to.

Josh: The Yamaha for how confidence-inspiring and stable the chassis is. But the Kawasaki was right there with it.

Mark: The Kawasaki. Its engine and suspension package are so versatile and predictable, and that counts for a lot on a slippery track with gnarly sharp-edged bumps.

Phil: The Kawasaki. Which really surprised me because I’ve never been a big fan. But there’s no denying it’s plush and balanced and easy to ride fast straight away.

Best bike Overall…

Luke: The Suzuki or Honda. It really like how nimble the Honda’s chassis is and how much adjustability the air fork gives you on different types of track. The power’s not as strong as some bikes off the bottom, but the way I ride, I don’t feel that.

Beau: The Kawasaki. Hands down. Just can’t fault it.

Josh: The Yamaha. The engine is deceptively fast and its stable chassis gives you so much more confidence to attack obstacles. It also wears you out slower.

Mark: The Yamaha. Weird choice for me, I know, as it’s a big bike and the suspension is firm. I just felt I could flow on it the best as its chassis was so stable and so predictable.

Phil: The Suzuki… But only if that vague feel to the fork on corner entries could be fixed. Otherwise, the Kawasaki.

Want to view this information in magazine form? Grab yourself a print or digital edition of Transmoto’s February Issue. Don’t forget to check out our exclusive video content from the test below, as well as our online image gallery.

Be the first to comment...