Mark Davidson Tells Tales Of Dakar Despair

The Dakar is one of those races. One of those races that no matter whether you finished, no matter where you’ve placed, you’re damn well guaranteed to come out of the experience with a hell of a story to tell. Mark Davidson decided that 2014 was to be his year to attempt the fabled race, and at the age of 55, he was actually the oldest rider in the field. To put that in perspective, Number #122 – Belgian rider Eric Palante, who started next to Mark – was 51 years old. He was racing his eleventh Dakar and sadly, he perished during Stage 5.

After such an incredible and harrowing experience, we thought we’d pose the question to mark: would he do it again? “Absolutely not. I’m happy to have ‘been there and done that’ with Dakar.”

Mark picks up the story of his adventure back in January…

The third day of my 2014 Dakar attempt started at 5am, and I was running 103rd after having a fairly strong day two in the first dune stage. Stage 3 was to be the first of the two Marathon Stages and the route was to take us up to an unprecedented elevation of 4400m. I was acutely aware of my previous problems with altitude sickness, but thought I had conquered it after months of training at a synthetic 3000m and the medication I’d been taking for the previous five days.

The route had been altered due to some significant rainfall and was reduced from 350km to 230km.

The first part of the stage featured rocks, riverbeds and singletrack with deep fesh fesh – aka bull dust. The terrain was more like an enduro course than a traditional Dakar stage – often tight and very technical.

The feature and challenge of the third stage were the three mountain climbs. The roadbook showed we would climb from 1000m to 4400m in just under 80km, traversing the three summits. This altitude had been reached in previous years, but not on a competitive stage and not in the extreme conditions that awaited us.

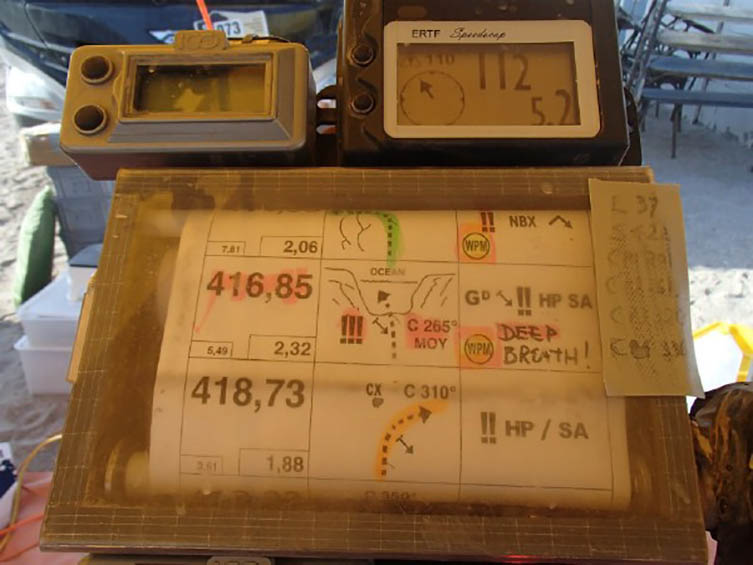

“The road book showed we would climb from 1000masl to 4400masl in just under 80km traversing the three summits.”

I reached the first mountain and cleared it well, but the second was a different matter. It was so long and so steep that I couldn’t see the top because of my neckbrace restriction. I hit it as fast and as hard as I could. The strength of KTM’s RR engine is well known, but here it even started to falter due to the lack of oxygen. I got to about 300m short of the summit and could feel the altitude hit both me and the bike’s engine – but the KTM fared better than me. I was slipping the clutch for the final 100m climb and the head spin became serious.

At the top of this climb I was feeling very weird. I had to rest. But the more I rested, the worse I got.

For those who have never experienced altitude sickness it’s a strange, un-nerving and potentially life-threatening experience.

For me, first came the dizziness, then the migraine-like headache followed by the vomiting.

I cleared the second summit – I think – at about 4pm. I then took a look at the final climb – 1,500m in one go. ‘F@#k me!,’ I thought to myself.

This is where it all becomes a little vague. I took the air filter off to help the bike breathe, but I don’t really remember the climb itself. I got stuck just short of the summit in what can only be described as a rock garden; the likes of which wouldn’t be out of place in an extreme enduro event. The only way through was to walk the 200kg bike through. That’s hard at the best of times, but when you add the altitude and the tiredness, it became almost an impossible task.

I’m not really sure how long it took but I managed to get through and rest at the top. If I dropped the bike once, I dropped it 20 times. And each time I picked it up, it just got heavier and heavier. I took stock of my situation. It was now late, about 7pm. I had reached the top and only had 70km to ride to the bivouac – dinner, bed and rest.

The only problem I had was that there were a myriad of tracks at the summit; some leading to another summit in the distance, some to the left and some to the right. I decided to take the one to the left that vaguely looked like the CAP [compass] bearing on the roadbook. It led to very steep ravine – once entered, there was no return. There were tracks in front of me, and I passed a very smashed-up quad of last year’s winner, Marcos Patronelli. This was a good sign – if he had been here, I must have the good track. I had dropped maybe 300-400m in the space of 1 or 2km. It was like going down a black ski run – so steep and so rocky.

As the ravine levelled out, I came across another quad, number 284. It had overturned in the big rocks and its pilot was trapped underneath. I stopped and managed to pull him free. His right arm was broken in several places and he complained of either broken ribs or some internal injuries. He had no English and I no Spanish. I called Paris on the Iritrac to report. This is where the real fun began.

“His right arm was broken in several places and he complained of either broken ribs or some internal injuries – he had no English and I no Spanish.”

By now, it’s about 7:45pm and it’s starting to get dark in the ravine. Paris tells me: “You are in the wrong ravine, and unless 284’s injuries are life-threatening, there will be no helicopter tonight. It’s mayhem on the mountain and far too dangerous to send a helicopter into a ravine with failing light. Besides, you will not be able to find your way out in the dark, you have two rivers to cross and there are steep cliffs. Your instructions are to stay with 284 and we will have a chopper to you at first light.”

I looked at the quad. It said Ricky Rios was its pilot. Was he going to die? I didn’t think so, but I’m no doctor. I told Paris this and also about my illness: “Very good monsieur,” they said. “Keep him warm, relax yourself and try not to sleep. It is best if you stay awake and drink lots of water – you do have your safety equipment, yes?”

Ricky and I spent a long night in that cold ravine together; 4000m up, with no food, only water from my bashplate and a measly space blanket each. At about 10pm I gave him two morphine tablets that I had been carrying. Poor old Ricky went comatose on me. ’I think I’ve killed him – he won’t wake up, he has a pulse but it’s only slight,’ I thought to myself. Around 2am he stirred, but with a raging thirst and he wanted to consume all our water. He spoke in his native tongue, me in mine, and neither of us knew what each other was saying. Did we care? No, at least we could both talk.

^ From Left: Troy O’Connor, Shane Diener and Alan Roberts. Three Aussies that crossed the Dakar ’14 finish line in 37th, 38th and 39th, respectively.

At dawn, I heard the chopper approaching – I set off my safety flare to signal our location but wondered where it was going to land – the only flat spot was about the size of a small kitchen. The chopper they sent was one of those really small little bubble jobs – pilot and a doctor, nothing else. ‘Looks like Ricky’s going home on the outside,’ I thought.

We wrapped up old Ricky in this trick suction blanket thing that restricts all movement. I remember now that I didn’t tell the doctor about the morphine. Once they were satisfied, they hauled him aboard. The doctor gave me some water and biscuits and told me to call Paris and they will ’walk‘ me out. Hasta la vista, Ricky.

I packed up, put the bashplate back on the bike and padded up. I hit the starter – f#@k, flat battery! All the calls to Paris all night had drained the thing. I went searching for the battery in the quad for a jump-start, but I can’t find it anywhere. I had say, 30m of downhill before big rocks. Bump start? Sure. Choke on, choke off? I only get one go at this. No choke. Let’s go. Then all of the sudden, bang. I’d nailed it!

I called Paris and told ’em I’m ready to roll. “Okay, 121, you have about 50km of off-piste to ride,” they replied. “It will be hard, and it will take some time. This is what we will do. You press your green button now. That will give me your position, I will then give you CAP and distance to follow. When you get to the distance press the green button again. Then call me back and we repeat the process. Roger that, 121?”

That 50km took me five hours. Sometimes old Pierre was on the money, other times he would send me into a vertical cliff face. I’d then back-track and find a better way. So it went for hours.

I rolled into the bivouac at about 11:30am. I’d left the last bivouac the previous morning at 5am, so by this point I’d been going for some 29 hours.

And that’s where the TV picks up the story. Ten minutes to rest, then straight into the next stage – 340km of hard rocky terrain – still at an altitude of 3000m.

So what happened next? I rode as well as I could but crashed often. I was so exhausted. Sometime around 6pm, at the 120km mark, I parked up and called Paris for the last time. Old Pierre answered: “Nice to hear from you, 121. The medics have been shadowing you for some time. Stay where you are. They will be with you shortly. Bravo to you.”

My Dakar ended there, on a lonely plain.

Kevin Muggleton, an American-based Brit, is the big guy in the video shown above. He went out during Stage 3. Unbeknown to me, he was waiting for me. Troy rounded him up that night and asked him to stay in the bivouac until I arrived, no matter what time I arrived, and do whatever needed to be done to keep me rolling. When you watch the video, you can hear him telling me the last rider left 20 minutes ago. He told me that to give me hope – the last rider in fact left four hours previously – but it worked! You can almost see my face change in seconds…

Be the first to comment...